This illustration has been created by AI to us only in this article.

Democracies are inherently fragile; they depend on a healthy body politic, and corruption is the cancer that turns it malignant. Although often taken for granted as the world’s only broadly legitimate form of government, with nearly all countries claiming to be some form of democracy, its global prevalence is a relatively recent development. The second and third waves of democratization after World War II were not the result of the inevitable march of human progress, but rather the direct product of U.S. influence and intervention.

For the past 80 years, American foreign policy has positioned itself at the center of a new world order—one that champions multilateral cooperation, free-market capitalism, and liberal democracy. From the postwar reconstruction of Europe and Japan to the creation of intergovernmental organizations and global financial institutions, the past century has been defined by massive U.S. investment in shaping the rules of trade, diplomacy, and conflict resolution around its own interests. However, while these developments often supported liberal democracy, in nearly every case where the U.S. had to choose between a nation’s self-determination and its own strategic interests, it chose the latter.

During the height of the Cold War, the liberal world order still gave way to military coups, proxy wars, and sponsorship of authoritarian regimes wherever American leadership believed such actions maintained global stability. In countries as far-flung as Chile, the Congo, Iran, and Vietnam, an expanding security state within the executive branch toppled governments in pursuit of global dominance by any means necessary—even at the cost of democratic freedoms and significant loss of life among local populations. As global hegemon and with the need to react quickly to international crises—something Congress is structurally unable to do—the presidency gradually consolidated power with dwindling constraints from the legislative or judicial branches.

While the foundation for these changes was laid during the Cold War and capitalized upon immensely during the Global War on Terror, the consequences of an increasingly imperial presidency have culminated under the Trump administration: a presidency marked by rampant corruption, repudiation of democratic norms and processes, and a mission to brutally punish political opposition. President Trump’s style of governance marks a sharp break from long-standing democratic norms and from the United States’ role—however flawed—as a global example of democracy. His efforts to subvert institutional checks and balances, combined with the corruption endemic to his administration, carry consequences that extend far beyond U.S. borders. Experts and allies alike must confront a critical question: what does an illiberal America project onto the world in place of democracy?

The Business of Power

Criticisms of the structural contradictions between liberal democracies and the coercive security states they deploy are nothing new; nor is corruption without precedent in American political history. Moreover, Trump’s zanier schemes often garnering the most publicity—such as throwing a military parade on his birthday, threatening Canada with annexation, or tossing around the idea of putting his face on Mount Rushmore, in true autocrat fashion—these theatrics, though bizarre and unfit for a modern U.S. president, are not ultimately what will have the longest lasting impact on the United States or the world.

is a researcher and policy analyst specializing in environmental security, financial crime, and East Asian affairs. He holds a Master’s in International Relations from American University and has worked in the U.S. Senate.

Democracies are inherently fragile; they depend on a healthy body politic, and corruption is the cancer that turns it malignant. Although often taken for granted as the world’s only broadly legitimate form of government, with nearly all countries claiming to be some form of democracy, its global prevalence is a relatively recent development. The second and third waves of democratization after World War II were not the result of the inevitable march of human progress, but rather the direct product of U.S. influence and intervention.

For the past 80 years, American foreign policy has positioned itself at the center of a new world order—one that champions multilateral cooperation, free-market capitalism, and liberal democracy. From the postwar reconstruction of Europe and Japan to the creation of intergovernmental organizations and global financial institutions, the past century has been defined by massive U.S. investment in shaping the rules of trade, diplomacy, and conflict resolution around its own interests. However, while these developments often supported liberal democracy, in nearly every case where the U.S. had to choose between a nation’s self-determination and its own strategic interests, it chose the latter.

During the height of the Cold War, the liberal world order still gave way to military coups, proxy wars, and sponsorship of authoritarian regimes wherever American leadership believed such actions maintained global stability. In countries as far-flung as Chile, the Congo, Iran, and Vietnam, an expanding security state within the executive branch toppled governments in pursuit of global dominance by any means necessary—even at the cost of democratic freedoms and significant loss of life among local populations. As global hegemon and with the need to react quickly to international crises—something Congress is structurally unable to do—the presidency gradually consolidated power with dwindling constraints from the legislative or judicial branches.

While the foundation for these changes was laid during the Cold War and capitalized upon immensely during the Global War on Terror, the consequences of an increasingly imperial presidency have culminated under the Trump administration: a presidency marked by rampant corruption, repudiation of democratic norms and processes, and a mission to brutally punish political opposition. President Trump’s style of governance marks a sharp break from long-standing democratic norms and from the United States’ role—however flawed—as a global example of democracy. His efforts to subvert institutional checks and balances, combined with the corruption endemic to his administration, carry consequences that extend far beyond U.S. borders. Experts and allies alike must confront a critical question: what does an illiberal America project onto the world in place of democracy?

The Business of Power

Criticisms of the structural contradictions between liberal democracies and the coercive security states they deploy are nothing new; nor is corruption without precedent in American political history. Moreover, Trump’s zanier schemes often garnering the most publicity—such as throwing a military parade on his birthday, threatening Canada with annexation, or tossing around the idea of putting his face on Mount Rushmore, in true autocrat fashion—these theatrics, though bizarre and unfit for a modern U.S. president, are not ultimately what will have the longest lasting impact on the United States or the world.

is a researcher and policy analyst specializing in environmental security, financial crime, and East Asian affairs. He holds a Master’s in International Relations from American University and has worked in the U.S. Senate.

The Chinese Experience That Challenges the Universality of Liberalism

What distinguishes the first six months of Donald Trump’s second term from past administrations is the unprecedented scope and speed with which he has dismantled institutional guardrails, not merely to enrich himself but to inflict lasting damage on a system that may prove difficult to repair. It is worth noting that corruption for private gain has been so rampant in this presidency that comparisons to the Gilded Age are not only becoming common but increasingly justified. In addition to receiving a Boeing 747 from the Qatari government, a move many experts argue directly violates the Foreign Emoluments Clause, the president has repeatedly used his office to advance his own business interests and those of his close allies.

Donald Trump’s cryptocurrency ($TRUMP) and “Make America Great Again” merchandise have more than doubled his fortune to an estimated $5.1 billion—an arrangement the White House maintains does not constitute a conflict of interest. Meanwhile, Elon Musk, as the richest man on Earth, was permitted to use the White House lawn to showcase new Tesla models, as the president gave a glowing endorsement from behind the wheel. However, behind these headline-grabbing stunts is a deliberate strategy to tear down safeguards against abuse.

On day one of President Trump’s second term, agencies across the executive branch began to be gutted, led either by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) or by the newly confirmed heads of agencies hand-picked for their loyalty to the new administration. U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) was dismantled entirely. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) was shut down. But nowhere was this more evident than in the systematic dismantling of anti-corruption institutions, the rollback of financial regulations, and the suspension of transparency laws.

Legalized Lawlessness

Under the pretense of easing burdens on corporations and business owners, the new administration launched a sweeping assault on the regulatory frameworks and oversight institutions essential to combating corruption. Among the earliest casualties were Task Force KleptoCapture, the Justice Department’s Kleptocracy Team, and the Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative, specialized units within the Justice Department tasked with investigating high-level financial crimes with global implications.

What distinguishes the first six months of Donald Trump’s second term from past administrations is the unprecedented scope and speed with which he has dismantled institutional guardrails, not merely to enrich himself but to inflict lasting damage on a system that may prove difficult to repair. It is worth noting that corruption for private gain has been so rampant in this presidency that comparisons to the Gilded Age are not only becoming common but increasingly justified. In addition to receiving a Boeing 747 from the Qatari government, a move many experts argue directly violates the Foreign Emoluments Clause, the president has repeatedly used his office to advance his own business interests and those of his close allies.

Donald Trump’s cryptocurrency ($TRUMP) and “Make America Great Again” merchandise have more than doubled his fortune to an estimated $5.1 billion—an arrangement the White House maintains does not constitute a conflict of interest. Meanwhile, Elon Musk, as the richest man on Earth, was permitted to use the White House lawn to showcase new Tesla models, as the president gave a glowing endorsement from behind the wheel. However, behind these headline-grabbing stunts is a deliberate strategy to tear down safeguards against abuse.

On day one of President Trump’s second term, agencies across the executive branch began to be gutted, led either by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) or by the newly confirmed heads of agencies hand-picked for their loyalty to the new administration. U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) was dismantled entirely. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) was shut down. But nowhere was this more evident than in the systematic dismantling of anti-corruption institutions, the rollback of financial regulations, and the suspension of transparency laws.

Legalized Lawlessness

Under the pretense of easing burdens on corporations and business owners, the new administration launched a sweeping assault on the regulatory frameworks and oversight institutions essential to combating corruption. Among the earliest casualties were Task Force KleptoCapture, the Justice Department’s Kleptocracy Team, and the Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative, specialized units within the Justice Department tasked with investigating high-level financial crimes with global implications.

These teams handled cases ranging from sanction evasion by Russian oligarchs bankrolling the invasion of Ukraine to billion-dollar corruption schemes, often working to recover stolen assets and return them to victims around the world. Disbanding these teams not only abandoned critical commitments to U.S. partner nations and shelved cases with national security implications, but also dismantled expert networks that had taken decades to develop.

Meanwhile, the same Justice Department froze enforcement on cornerstone anti-bribery laws such as the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). Once considered the gold standard for international anti-bribery enforcement, the regulation was paused under the newly appointed U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi. Her career with President Donald Trump began in his first term and has been defined by her unwavering support, going as far as attempting to overturn the results of President Joe Biden’s 2020 electoral victory in Pennsylvania and perpetuating the conspiracy theory that the election was fraudulent.

Prosecutions have slowed to a near halt, and large cases against multinationals were quietly abandoned. Foreign influence in U.S. politics, already a growing concern, now faces even fewer barriers. Earlier this month, one of the most significant targets has been the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA), a 2021 law passed with bipartisan support that required companies to disclose beneficial ownership to deter money laundering, tax evasion, and illicit finance. The Treasury Department, then headed by a close family friend to the president, Scott Bessent, would eventually issue a new rule exempting domestic entities from reporting obligations and changing the definition of what a “reporting company” is to only include entities formed under foreign law.

The same Justice Department froze enforcement on cornerstone anti-bribery laws such as the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA).

In other words, American companies and beneficial owners do not need to follow the law; the law only applies to foreigners. The CTA represented a culmination of over a decade of work on the part of experts, activists, and representatives in Congress, in addition to pressure from international organizations like the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), to combat the flow of criminal funds. Consequently, the rule change drew ire from both Republican and Democratic senators, claiming it violated congressional intent, with a joint statement requesting it be reversed.

But by delaying implementation deadlines, narrowing the definition of reportable entities, and stripping key agencies like Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) of necessary funding and authority to act, the Trump administration effectively defanged one of the most significant anti-corruption laws in a generation. One of the most alarming trends of the past six months is the extent to which the administration’s second-term agenda is being carried out by loyalists with direct personal or political ties to the president.

Nearly every cabinet member fits this mold—either close family and friends (Bessent, Lutnick), former politicians who have aligned themselves with the MAGA movement (Gabbard, Ratcliffe, Zeldin), or fringe figures pushing its more extreme elements (RFK Jr., Noem). This prioritization of loyalty over competence often results in what is known as a kakistocracy—government by the least qualified—which can have devastating long-term effects on public administration.

More concerning still, the executive appears intent on embedding this model throughout the federal bureaucracy and civil society. Agencies that historically operated with degrees of independence—like the Department of Justice, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Securities and Exchange Commission—have seen senior staff replaced with ideologically aligned loyalists, a key aspect of democracies that succumb to authoritarianism. Investigations into politically sensitive topics have been quashed or redirected, and legal memos have been rewritten to justify previously untenable interpretations of executive authority.

And while personal grift may grab headlines, the long-term impact of regulatory and institutional erosion is far more profound. These systems exist not only to prevent corruption, but to ensure the U.S. government functions with legitimacy in the eyes of its citizens and global partners. When those systems are eliminated or weaponized against political opponents, the legitimacy built by architects of American foreign policy for the past several decades shatters. When the world’s most powerful democracy abandons its own guardrails, it reshapes the norms and expectations of the global order itself.

Global Democracy Abandoned

The strategy employed by Donald Trump in the United States mirrors patterns seen in countries undergoing autocratic takeovers. In Türkiye, following a failed coup attempt in 2016, President Erdoğan purged tens of thousands from the civil service, replacing judges, bureaucrats, and military leaders with party loyalists. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán consolidated power by stacking the judiciary, media, and universities with political allies, turning once-independent institutions into instruments of partisan control.

And in Russia, Putin built an oligarchic system by elevating loyalists from the security services and inner circle, sacrificing expertise for loyalty at every level. But on day one of Trump’s second term, the United States crossed into unprecedented territory: nowhere in world history has the preeminent global power willingly descended into kleptocracy. The international consequences of America’s democratic backslide are immediate and profound. For decades, U.S. support, whether rhetorical, financial, or diplomatic, played a critical role in bolstering anti-corruption efforts, empowering civil society, and legitimizing democratic reformers across the globe.

That credibility has been terminally damaged. As the U.S. dismantles transparency laws and weakens institutional oversight from the Oval Office, autocrats and skeptics alike gain a powerful new talking point: if this is the best the world’s leading democracy can offer, then democracy isn’t worth it. Moreover, Trump’s approach to foreign policy—transactional, indifferent to human rights, and deeply hostile to multilateralism—further isolates democratic movements. From Belarus to Burma, activists who once looked to Washington for moral support and strategic leverage now find themselves abandoned.

In their place, autocrats court alliances with China and Russia, whose assistance comes with no expectation of reform. The long-term risk is not just reputational, but systemic. As leadership collapses, global efforts to curb kleptocracy and authoritarianism crumble with it. The result is a rising tide of impunity: regimes emboldened, opposition movements stifled, and the international order reshaped in the image of those who rule without constraint.

These teams handled cases ranging from sanction evasion by Russian oligarchs bankrolling the invasion of Ukraine to billion-dollar corruption schemes, often working to recover stolen assets and return them to victims around the world. Disbanding these teams not only abandoned critical commitments to U.S. partner nations and shelved cases with national security implications, but also dismantled expert networks that had taken decades to develop.

Meanwhile, the same Justice Department froze enforcement on cornerstone anti-bribery laws such as the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). Once considered the gold standard for international anti-bribery enforcement, the regulation was paused under the newly appointed U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi. Her career with President Donald Trump began in his first term and has been defined by her unwavering support, going as far as attempting to overturn the results of President Joe Biden’s 2020 electoral victory in Pennsylvania and perpetuating the conspiracy theory that the election was fraudulent.

Prosecutions have slowed to a near halt, and large cases against multinationals were quietly abandoned. Foreign influence in U.S. politics, already a growing concern, now faces even fewer barriers. Earlier this month, one of the most significant targets has been the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA), a 2021 law passed with bipartisan support that required companies to disclose beneficial ownership to deter money laundering, tax evasion, and illicit finance. The Treasury Department, then headed by a close family friend to the president, Scott Bessent, would eventually issue a new rule exempting domestic entities from reporting obligations and changing the definition of what a “reporting company” is to only include entities formed under foreign law.

In other words, American companies and beneficial owners do not need to follow the law; the law only applies to foreigners. The CTA represented a culmination of over a decade of work on the part of experts, activists, and

representatives in Congress, in addition to pressure from international organizations like the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), to combat the flow of criminal funds. Consequently, the rule change drew ire from both Republican and Democratic senators, claiming it violated congressional intent, with a joint statement requesting it be reversed.

But by delaying implementation deadlines, narrowing the definition of reportable entities, and stripping key agencies like Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) of necessary funding and authority to act, the Trump administration effectively defanged one of the most significant anti-corruption laws in a generation. One of the most alarming trends of the past six months is the extent to which the administration’s second-term agenda is being carried out by loyalists with direct personal or political ties to the president.

Nearly every cabinet member fits this mold—either close family and friends (Bessent, Lutnick), former politicians who have aligned themselves with the MAGA movement (Gabbard, Ratcliffe, Zeldin), or fringe figures pushing its more extreme elements (RFK Jr., Noem). This prioritization of loyalty over competence often results in what is known as a kakistocracy—government by the least qualified—which can have devastating long-term effects on public administration.

More concerning still, the executive appears intent on embedding this model throughout the federal bureaucracy and civil society. Agencies that historically operated with degrees of independence—like the Department of Justice, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Securities and Exchange Commission—have seen senior staff replaced with ideologically aligned loyalists, a key aspect of democracies that succumb to authoritarianism. Investigations into politically sensitive topics have been quashed or redirected, and legal memos have been rewritten to justify previously untenable interpretations of executive authority.

And while personal grift may grab headlines, the long-term impact of regulatory and institutional erosion is far more profound. These systems exist not only to prevent corruption, but to ensure the U.S. government functions with legitimacy in the eyes of its citizens and global partners. When those systems are eliminated or weaponized against political opponents, the legitimacy built by architects of American foreign policy for the past several decades shatters. When the world’s most powerful democracy abandons its own guardrails, it reshapes the norms and expectations of the global order itself.

Global Democracy Abandoned

The strategy employed by Donald Trump in the United States mirrors patterns seen in countries undergoing autocratic takeovers. In Türkiye, following a failed coup attempt in 2016, President Erdoğan purged tens of thousands from the civil service, replacing judges, bureaucrats, and military leaders with party loyalists. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán consolidated power by stacking the judiciary, media, and universities with political allies, turning once-independent institutions into instruments of partisan control.

And in Russia, Putin built an oligarchic system by elevating loyalists from the security services and inner circle, sacrificing expertise for loyalty at every level. But on day one of Trump’s second term, the United States crossed into unprecedented territory: nowhere in world history has the preeminent global power willingly descended into kleptocracy. The international consequences of America’s democratic backslide are immediate and profound. For decades, U.S. support, whether rhetorical, financial, or diplomatic, played a critical role in bolstering anti-corruption efforts, empowering civil society, and legitimizing democratic reformers across the globe.

That credibility has been terminally damaged. As the U.S. dismantles transparency laws and weakens institutional oversight from the Oval Office, autocrats and skeptics alike gain a powerful new talking point: if this is the best the world’s leading democracy can offer, then democracy isn’t worth it. Moreover, Trump’s approach to foreign policy—transactional, indifferent to human rights, and deeply hostile to multilateralism—further isolates democratic movements. From Belarus to Burma, activists who once looked to Washington for moral support and strategic leverage now find themselves abandoned.

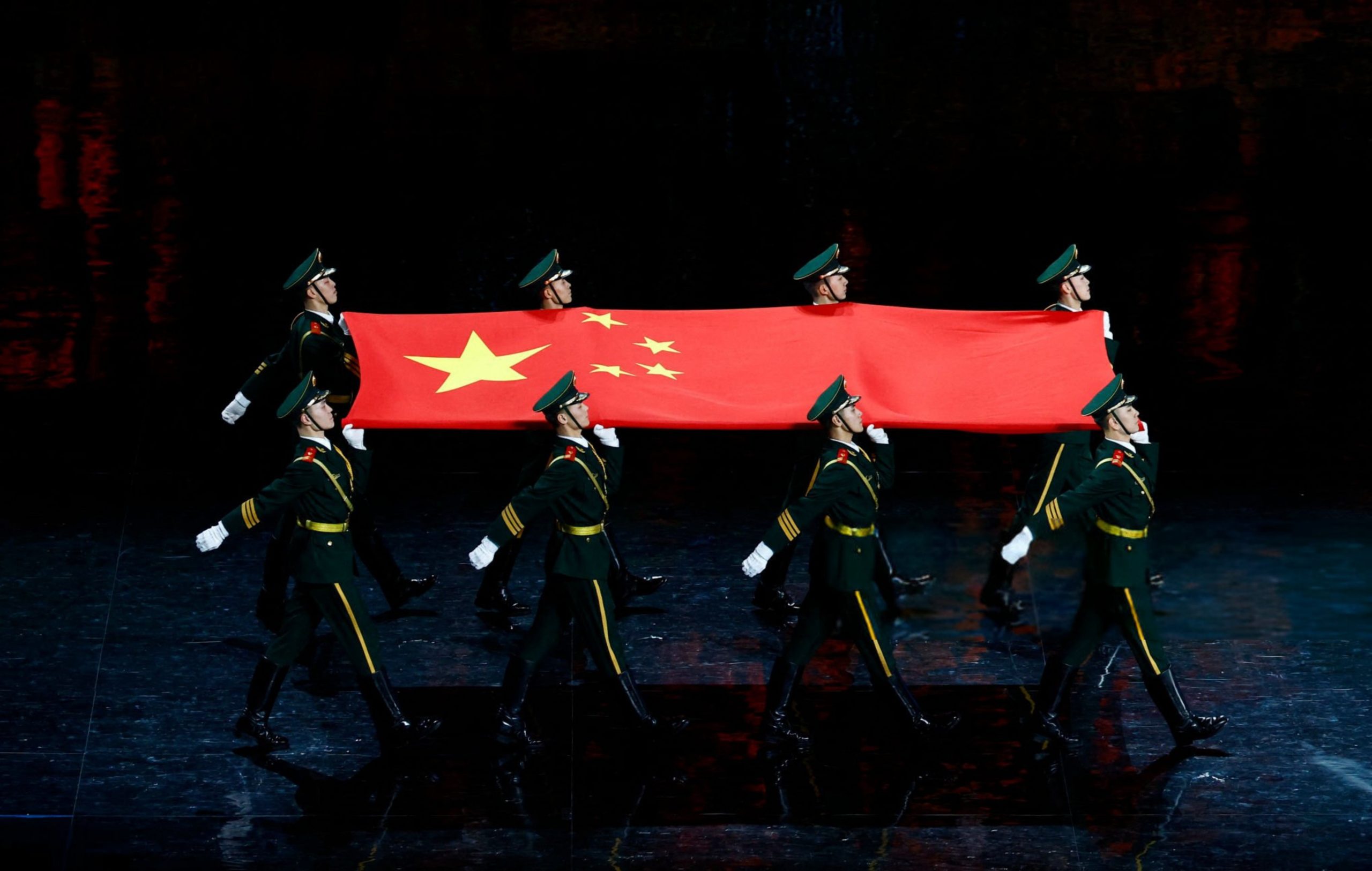

In their place, autocrats court alliances with China and Russia, whose assistance comes with no expectation of reform. The long-term risk is not just reputational, but systemic. As leadership collapses, global efforts to curb kleptocracy and authoritarianism crumble with it. The result is a rising tide of impunity: regimes emboldened, opposition movements stifled, and the international order reshaped in the image of those who rule without constraint.

Recommended

Trump’s America and the End of Global Trust

The Exhaustion of Democracy Promotion

What is the Ideal American Foreign Policy in the Multipolar World?

The Fallout of Trump’s Policies

Why Trump’s Russia Strategy Won’t Work