Hope for stepping back from the precipice best rests on bringing difficult questions of values and political culture—and their compatibility with the liberal order—back to the table.

Written By; Foreign Analysis – Jun 24, 2022

It was only several weeks ago that President Joe Biden reaffirmed his administration’s high hopes for the United Nations (UN). Standing before the seventy-seventh session of the UN’s special assembly on September 21, Biden said, “The United States will always promote human rights and the values enshrined in the U.N. Charter,” adding that “this institution, guided by the U.N. Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, is at its core an act of dauntless hope.”

Two weeks later, Chinese state media was triumphantly touting Beijing’s success in derailing a U.S.-backed motion for the UN Council on Human Rights to discuss allegations of human rights abuses in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. It came after sixty-six mainly developing nations, including China, broke from Washington’s position by calling for a peaceful settlement of the war in Ukraine—which would likely reward Russian aggression by urging partial acquiescence to Moscow’s demands.

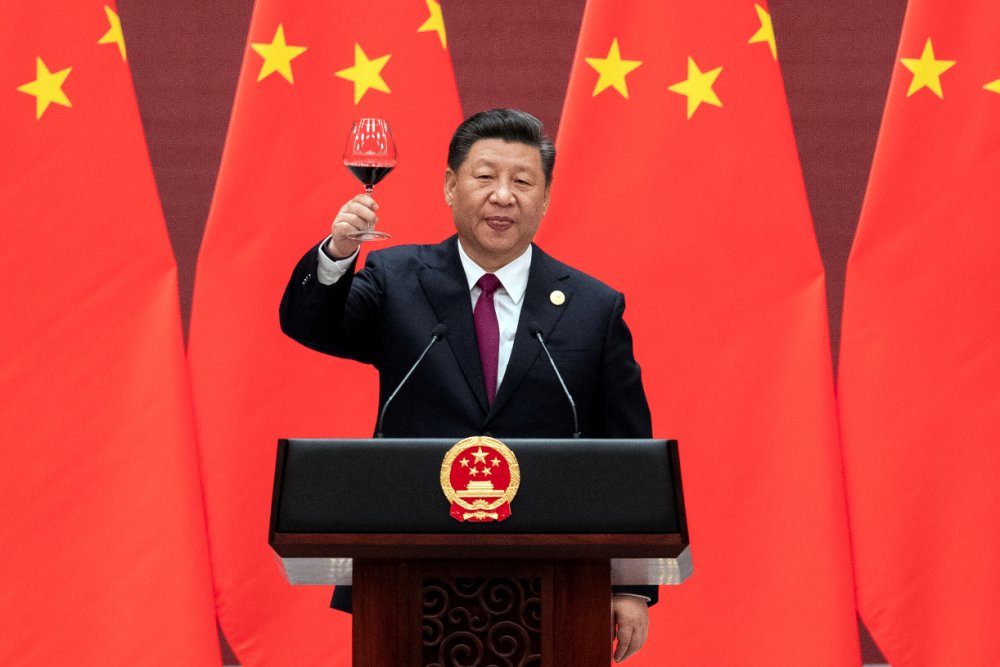

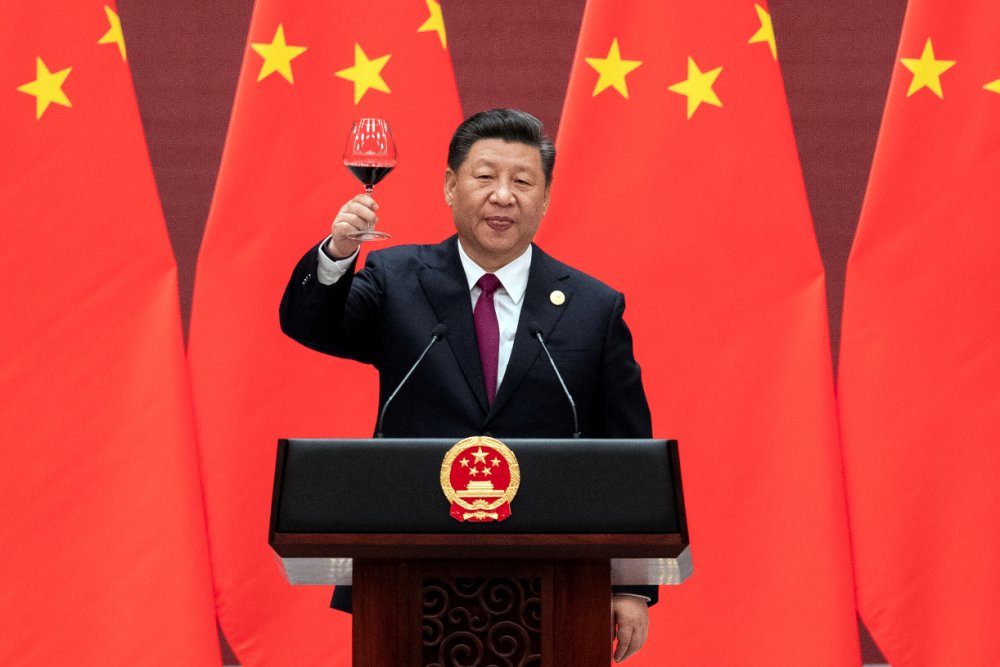

Both Biden’s Washington and Xi Jinping’s Beijing ostensibly agree that the UN and its affiliated organizations should continue to play a key role in global affairs. But fundamental differences between their understanding of what this role should be—especially in relation to the thorny issue of human rights—are eroding these institutions’ capacity to facilitate cooperation and settle territorial and distributional conflicts. On both sides of these differences, states are bypassing these institutions and turning instead to like-minded partners. Economic cooperation is booming between China and Russia, throwing a lifeline to Russia while much of the world continues to condemn its flagrant violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty. In a speech at the UN last year, Biden emphasized that the United States is “not seeking a new Cold War or a world divided into rigid blocs.” But reflecting a less optimistic view of these bodies’ potency—or perhaps to hedge against their subversion—Washington appears to be building multifaceted alliances aimed at containing China and Russia and expanding their purview so that they may operate parallel to a broadening spectrum of UN institutions and the liberal international market system.

Recognition of this reality is starting to rise from world leaders’ subconscious and is now puncturing the surface of political discourse. China’s ambassador to Australia, Xiao Qian, recently proclaimed that China aims to help sustain the rules-based order. Yet while Xi’s speech marking the opening of the 20th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party praised China’s growing “international influence, appeal and power to shape [the world],” its main emphasis was on mitigating growing dangers to China’s national security. While touting his commitment to finding “common ground” with other nations, Biden’s speech to the UN made no secret of where America stood in “the contest between democracy and autocracy.” And though the Biden administration’s recently released National Security Strategy outwardly spoke of protecting the “rules-based order,” it betrayed, according to international relations professor Van Jackson, an anti-globalist tone inspired by a new “national security Keynesianism” intended to “wield the economy as a weapon in rivalry with China and, to a lesser extent Russia.” Neither leader dared to acknowledge that their homages to the “rules-based order” poorly mask their devolution to an auxiliary geopolitical ballast, as competition and balance of power gradually re-assume their mantle as the primary shapers of international engagement. And no other leader dared to extrapolate on what this means: that the liberal world order as we have known it, which has helped sustain an unfettered period of global capitalism-driven prosperity, is nearing a close.