In recent times, the Biden administration’s security and economic initiatives focused on Asia have created a significant impact on regional stability and power balances. Particularly, formations such as AUKUS and the Quad are opening a new chapter in regional and global security architecture.

MARCH 05, 2024

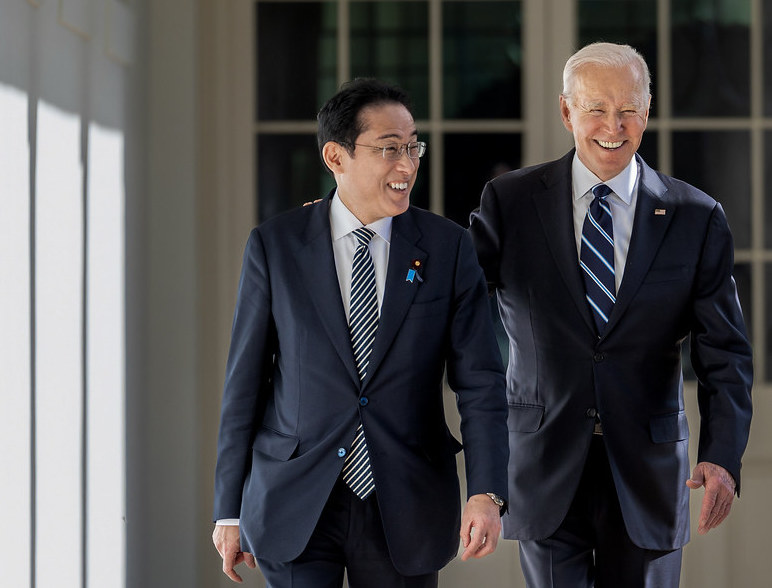

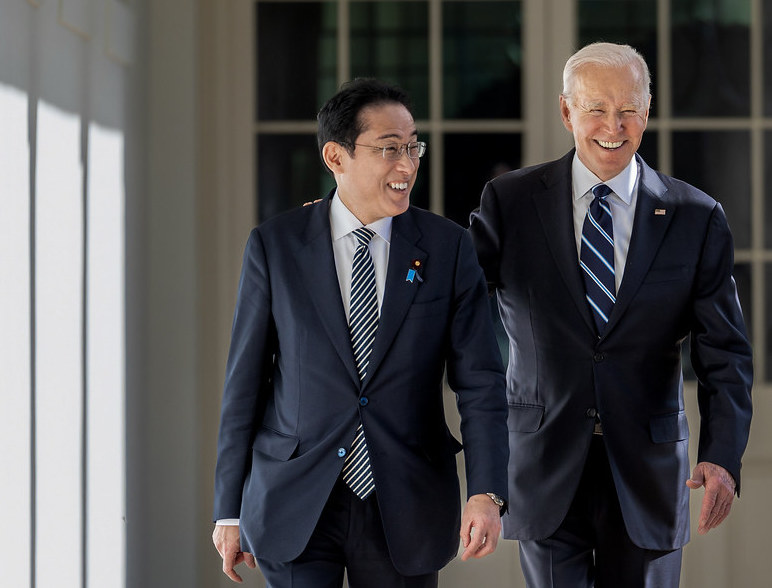

The Biden administration has pro-actively expanded bilateral and multilateral engagement in East Asia, including with its most important regional ally Japan. Is the crisscrossed web of economic and security initiatives sustainable enough to overcome uncertain domestic politics and deter China?

In a recent issue of Foreign Affairs, Jake Sullivan, the current National Security Advisor of the U.S., gave a broad outline of the Biden administration’s achievements and broader strategic vision. In what sometimes read as Mr. Sullivan going around the world and rattling off all the country’s various alliances, pacts, and agreements both old and new, the piece did underscore President Biden’s renewed commitment to internationalism after four years of the more isolationist Donald Trump.

On Asia, which was certainly the region the Biden administration wanted to place a heavier focus on before Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine and the renewed conflict in the Gaza Strip after October 7th 2023, he listed four main initiatives: the new trilateral cooperation between Japan, South Korea and the U.S., the trilateral security partnership between Australia, U.S. and UK (AUKUS), the broader quadrilateral partnership between Australia, India, Japan, and the U.S. (Quad) and the 13-country economically-oriented Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Peace and Prosperity (IPEF).

Japan, which is part of three of the four multilateral frameworks outlined above and remains the most important security partner of the U.S. in the region under the umbrella of the U.S.-Japan security alliance, has undoubtedly been pleased with these developments. Under current Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, the country has pursued a more pro-active foreign policy in the face of growing geopolitical challenges. It has positioned itself firmly with the West, sanctioning Russia and pledging about US$ 10 billion in aid to Ukraine, while adopting new security commitments at the 50-anniversary summit with ASEAN, the Southeast Asian regional bloc in December 2023.

As part of the latter, Japan announced an Official Security Assistance (OSA)—a security-focused aid framework complimentary to the country’s long-standing commitment to Official Development Assistance (ODA)—package for Malaysia, following a similar agreement with the Philippines in November 2023. OSA is partly made possible through eased arms export regulations, signifying a break with the country’s long-held tradition to avoid the transfer of lethal arms. Finally, Japan has also committed to double defense spending by 2027 to 2% of GDP, approving its largest ever defense budget for fiscal year 2024 in December 2024. That budget sees spending boosted by 16% to 7.95 trillion yen (US$56 billion) and achieving the 2027 target would see Japan become the world’s third largest military spender after the U.S. and China.

The Kishida administration has continued the policies of late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who was committed to a more activist, security-oriented foreign policy but ultimately did not have the political capital to change Japan’s pacifist constitution, which bars the country from pursuing war as a means to settle international disputes under Article 9. Kishida’s foreign policy increasingly exposes the contradiction between Japan’s long-held commitment to pacifism and its geopolitical realities.

The country is confronted with ever-more assertive neighbors in China, Russia and North Korea, with China’s challenges to the status quo in the Taiwan Strait and broader South China Sea specifically serving as the background to many of the policies outlined thus far. To reconcile this contradiction, Kishida has increasingly adopted values-based language, framing his foreign policy as a commitment to “free and open international order based on the rule of law,” an extension to the concept of a “free and open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP), which was made a pillar of the country’s foreign policy under Abe and adopted by the U.S. as well.

However, there are still numerous open questions about renewed U.S. and Japan-led multilateralism in Asia. Even assuming the various inititatives outlined by Mr. Sullivan, in combination with Japan’s (and South Korea’s) own engagement in region, are enough of a deterrent to maintain peace in the Taiwan Strait—which is by no means a given—the sustainability of these measures is key. While the trilateral summit between Japan, South Korea, and the U.S. at Camp David in August 2023 nominally united the three countries based on mutual geostrategic interests, it was arguably made possible due to Biden, Kishida, and South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol’s personal commitment to deepen ties.

All three of these leaders are suffering from low approval ratings, with Kishida and Yoon being among the most unpopular heads of state in the world. The Biden administration was clever in scheduling numerous trilateral meetings into the future—the first of which was a cybersecurity meeting in Japan in December 2023—that in theory should outlast regime change, but this is by no means guaranteed. Japan-South Korea relations deteriorated significantly following the election of the Democratic Party of Korea’s (DPK) more Japan-critical Moon Jae-in in 2017, which proceeded a similar push for trilateral engagement in the early 2010s.

It is also unlikely that a potential second Trump administration would show the same commitment to the trilateral alliance, or regional multilaterism as a whole, as Biden has. While Trump did enact tough economic policies targeting China, which spiralled into a trade war from 2018 to 2020, it is unlikely that he would be as pro-active, or interested, in maintaining the broad framework of deterrance that Biden is attempting to build in the region. The IPEF is symbolic of this: the entire project only became a neccessity after Trump withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which has evolved into the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) since, in January 2017.

Aside from Trump, the growing China-U.S. rivalry will also affect domestic politics in ASEAN countries, the majority of which do not wish to explicitly allign with one or the other. Amidst renewed security commitments between the Phillipines and the U.S. as well as Japan, and talk of a possible trilateral pact (JAPHUS), domestic infighting between the more China-friendly Duterte family and the ruling Marcos administration—who allied during the presidential election in 2022—has increased dramatically in recent months.

The return to power of the DPK in South Korea, a member of the Duterte clan in the Phillipines, or Donald Trump in the U.S., all have the potential to pose serious challenges to the evolving bilateral and multilateral security framework in the region. Japan is poised to remain a reliable partner, however. Even if Kishida is replaced—a scenario that is looking increasingly likely amidst political slush fund scandal involving members of his Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)—any potential successor is likely to broadly continue his foreign policy.

The above underscores how difficult it is to achieve sustainable security in East Asia and beyond. Of course, there is no collective security framework that mirrors NATO in the region. Instead, regional security depends on a serious of bilateral pacts and multilateral intitiatives that have all seen significant expansion under President Biden, who has benefited from willing regional partners, above all Japan. In the future, how effective and sustainable these are—and whether they will be enough to maintain the current status quo in Taiwan—will depend not only on China’s foreign policy decisions, but also increasingly on the domestic political dynamics in several of the region’s key players, and the U.S. itself.

A curated seletion of FA’s must-read stories.

Written By: SHAGNIK BARMAN

Written By: BERK TUTTUP

Written By: ABBY L’BERT

Written By: BILLY AGWANDA

Written By: HIRA SARWAR

Written By: BATUHAN GUNES

Written By: LEON REED

Written By: DARSHAN GAJJAR

Maximilien Xavier Rehm is a Ph.D Candidate at Doshisha University in Kyoto, Japan. His research focuses on Japanese politics, foreign policy, and migration policy. Maximilien’s writing has been featured in The Diplomat, The Japan Times, and East Asia Forum.

Written By: GABRIEL RAMIREZ

Written By: DILARA SAHIN

Written By: DILRUBA YILMAZ

Written By: NILAY CELIK

Written By: ELDANIZ GUSSEINOV

Written By: JOSEF SCHOEFL

Written By: SELCAN BEDIRHANOGLU

Written By: FATIH CEYLAN

FA’s flagship evening newsletter guilding you through the most important world streis ofthe day. Delivered weekdays.