Dive into the tale of South Africa’s journey from the inspiring inauguration of the ‘Rainbow Nation’ under Mandela’s leadership to the current trials of an ‘Embattled’ state, examining the interplay of dreams, disillusionment, and the ongoing struggle for a brighter future.

APRIL 01, 2024

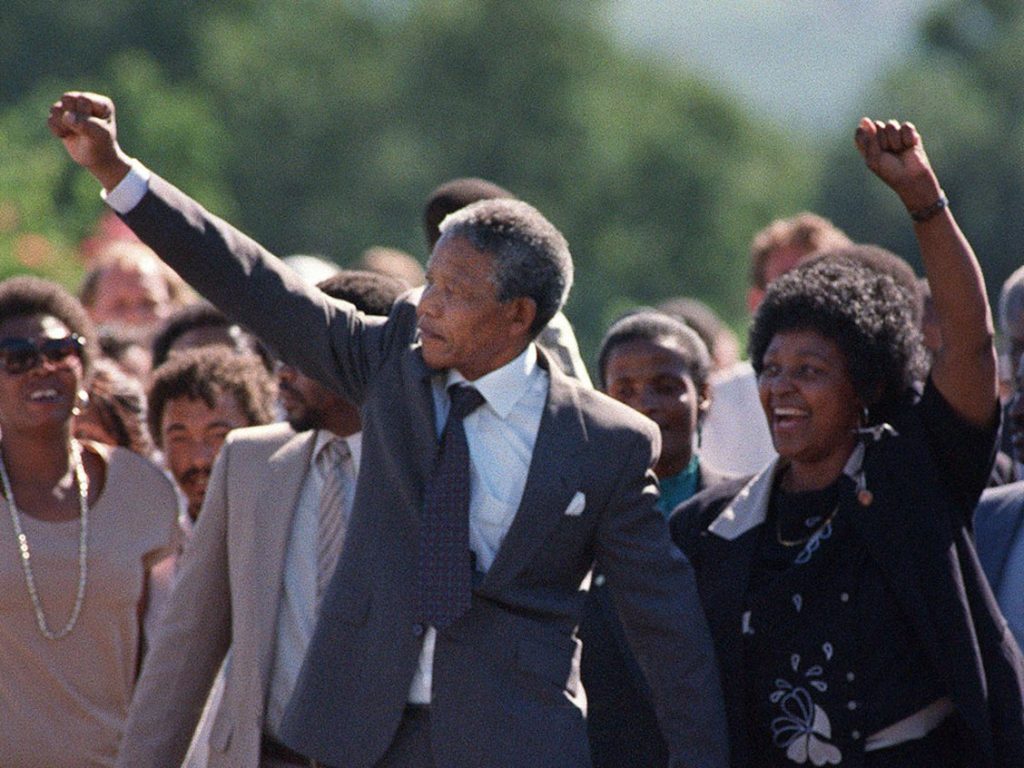

Nelson Mandela’s election as the first post-apartheid President of South Africa was a watershed moment in world history. Mandela’s victory was a symbolic end to the decades-long struggle for equality under the law. It marked one of the final victories in a continent-wide revolution to achieve self-rule and overcome the last vestiges of minority rule and colonization. Desmond Tutu’s widely adopted adage of the “Rainbow Nation” described a state seemingly united at home, eager to rectify its history of apartheid, and poised to lead the country to a future fulfilled by the promise of democracy, prosperity, and international influence. A global consensus emerged that South Africa was becoming the continent’s political and economic “powerhouse”; an island of stability in a troubled sea. Spin the clock ahead thirty years and the reality could not be more dissonant. The visions of the “powerhouse of Africa” have long faded. Deep-seated corruption, stark racial fissures, acute poverty, and a perpetual shortage of public confidence are overwhelming the country. The African National Congress (ANC) has been marred by infighting and stagnation. No viable national alternative has surfaced. Truly, South Africa is a shell of its once-bright future.

The causes of today’s crisis are deep-seated. On the surface level, the annual GDP per capita growth rate slowed to a dismal 1.2% average, the Gini coefficient, a statistical measure of income inequality, skyrocketed world-leading 62.1, and the annual fragility indicator sum measured by the Fund for Peace’s Fragile States Index maintained a perpetually high score of 72 (2023). While remarkable independently, these metrics only tell half the story. Mandela’s election inspired the “Powerhouse of Africa” dream as international investment flowed into South Africa. The dream caused mass mobilizations in civil society, leading to record-breaking political participation in elections and an unprecedented spirit of entrepreneurship. Open markets and free political processes catalyzed optimism for the “rainbow nation’s” future. Former President Thabo Mbeki’s warning of a “dream deferred” has materialized.” By the same token, Mamphela Ramphele, the former President of the Club of Rome, lamented “the fabric of the nation has eroded since the Mandela government.” Consequentially, the cause of today’s predicament is two-fold: the dissonance between the country’s once-lauded potential and reality and the confluence of sophisticated political, economic, and social challenges have pushed the country to a boiling point.

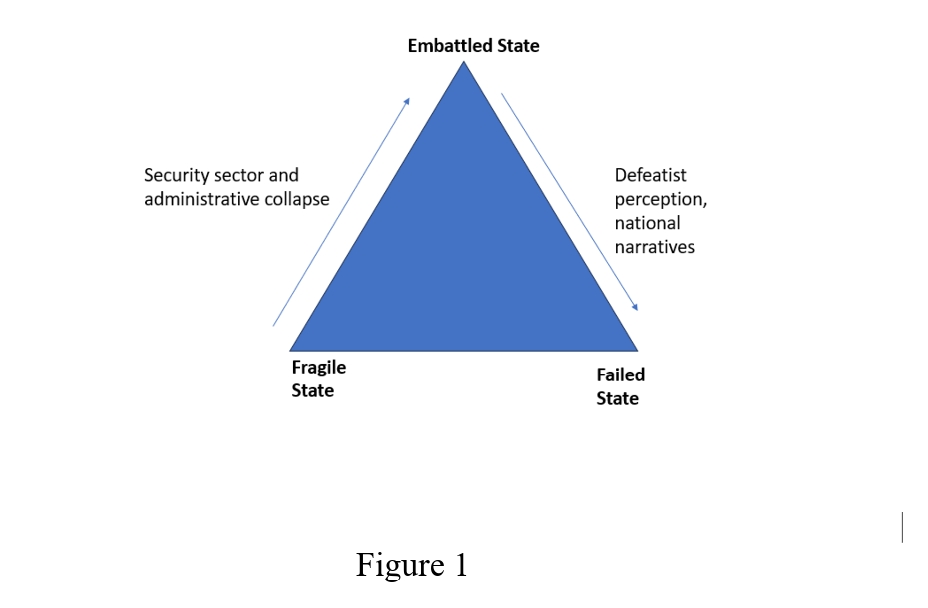

Those pitfalls have inspired contentious discussions, both internal and external, over the country’s direction. An increasing number of South African citizens and pundits alike consider their country a failed state. That perception is predicated on decades of ingrained corruption, consistent energy blackouts, substantial income inequality, and a tangible loss of confidence in the ANC as capable of governing. However, assuming that South Africa is already a failed state is far-fetched when compared to states like Syria, Afghanistan, Yemen, and Libya or others on the continent such as Somalia and South Sudan. At the other end of the spectrum are the proponents of the fragile state argument. Fragile states, as will be discussed later, exhibit erosion within a more robust capacity. Neither does the description of a fragile state capture the totality of the challenges and defeatist perceptions confronting Pretoria. To reiterate, since an increasing number of South Africans consider their country a failed state, but it is yet to display unambiguous, extreme signs of collapse, South Africa exists in a theoretical gap between the failed and fragile classifications. It is reasonable to assume that South Africa, given the significant disparity between its “dream” and reality coupled with the myriad of domestic and international stresses, implores expanding the traditional understanding of state fragility. Classifying South Africa on a continuum between fragile and failed states cannot accurately capture the toxic combination of fragility and collapse of public confidence. Shifting to another dimension and classifying South Africa as an “Embattled” state offers a nuanced concept of the country’s plight and future.

South Africa’s decline is among the greatest tragedies of the 21st Century. An expected regional and global leader, the country succumbed to factional disputes, corruption, and violence leaving in its place a barely recognizable nation. The hopes of becoming an economic engine for the region, expanding from a solid foundation of several major industries, and the political influence that emerged due to the rising social cohesion rooted in the vision of creating a “rainbow nation” is now out of the hearts and minds of most South Africans. Its once-celebrated potential is largely squandered. However, while South Africa exhibits substantial erosion and public narratives pronouncing its defeat, Pretoria’s fate is not sealed.

According to a study conducted by Richard Rawn of the CATO Institute, a failed state consists of three main criteria: physical insecurity, political illegitimacy, and administrative decay. When a country loses physical control over its agreed-upon borders, the monopoly of legitimate violence, the ability to project authority at home and abroad, and the capacity to perform administrative duties, it devolves from a fragile to a failed state. Simply put, erosion devolves into collapse. The study continues by labeling Syria, Afghanistan, Yemen, Libya, and Haiti as failed states. A fragile state, on the other hand, implies a susceptibility to pressures, not a surrender, of those three criteria. Fragile states can contain cancerous characteristics (such as an armed insurgency or institutional degradation) but are not at risk of immediate collapse. Every country holds aspects of fragility.

While many countries fall into both camps, studying fragility as a binary concept poses three theoretical challenges. First, under a binary premise, there is an assumption of a complete loss of agency between fragile and failed. In other words, states decline from fragile to failed because of variables outside of their control. That assumption poses a hasty generalization fallacy. In this model, countries like South Africa declined from fragile to “Embattled” largely because of their agency. Neglect or ill-fated policies typically cause states to decline from fragile to “Embattled” and then possibly, to failed. Second, assuming that every state is either fragile or failed prioritizes homogeneity over precision-based methodology. In practice, fragility is more fluid than stagnant. Countries such as Colombia and Pakistan have experienced varying degrees of fragility across their histories, sometimes resembling more of a fragile state and others teetering on the edge of failure. Finally, using a binary framework poses a definitional challenge for states outside the contours of fragile and failed.

A predicament emerges when a state collapses in one or two of Rawn’s criteria but is still functioning. This gap is addressed by the “Embattled” state hypothesis. The “Embattled” state possesses two main characteristics: erosion that appears to stress the contours of a fragile state (but is yet to meet the standard of a failed state) and defeatist public perceptions. Given this paradigm, fragility in “Embattled” states exists on a continuum rather than a binary premise. The essence of the “Embattled” state hypothesis hinges on defining states that have dichotomous security, legitimacy, and administrative sectors but are still functioning. “Embattled” states are comparable to “Schrodinger’s cat” as they include paradoxical characteristics, both dead and alive but neither conclusive to the other. In addition to South Africa, Brazil demonstrates an “Embattled” state.

Our “Embattled” state hypothesis is well documented in mainstream International Relations literature. Richard Rotberg, the former President of the World Peace Foundation, wrote in favor of the “Embattled” state proposal when he contended that fragility exists on a spectrum. Countries can transition between fragile, failing, and failed, he argues, and those transitions are based on agency; their placement is fluid and hinges on their decisions rather than stagnant and a result of foreign forces.

Figure 1 demonstrates two invaluable concepts. First, fragility is determined by a broad set of variables. Erosion and collapse, according to Rotberg, can coexist. A state may have a contested security sector and legitimacy challenges but provide uninterrupted governance and administrative functions or vice versa. Second, fluid variables such as public perceptions and prevailing national narratives play a decisive role in determining whether a state is fragile, “Embattled,” or failed. Public perceptions emanate from civil society organizations, mass media, and popular responses to government policy. For example, in South Africa, media outlets have decried the country as a failed state when it does not present cross-sector collapse.

There are two historical examples of “Embattled States.” First, Colombia during its trials against Pablo Escobar’s Medellin and the Rodriguez Brother’s Cali cartels typifies the “Embattled State” due to the legitimacy and administrative crises. Nevertheless, Colombia remained capable of carrying out governing services and later overcame its perceptive, security, and administrative threats. Similarly, the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights labeled Lebanon a ’failing’ country, tantamount to our “Embattled State.” Beirut’s inability to rectify the prolonged economic downturn, contain Hezbollah militant activity, and alleviate poverty caused its decline from fragile to ‘failing.’ Lebanon’s physical security is mostly intact, but its administrative departments show increased strain to the point of collapse, particularly after the 2020 Beirut Port Explosion. Accordingly, the “Embattled” State” offers the only viable explanation for Colombia and Lebanon’s predicaments as both countries demonstrated fragility outside the contours of fragile and failed states, agency-determined declines, and dissonant domestic compositions that have had significant projections of public skepticism of the viability of the state in the recent past. While South Africa has not declined to the level of collapse present in Colombia and Lebanon, its trajectory and public perceptions indicate the potential trajectory.

Our ‘Embattled State’ thesis offers valuable insight into other states’ post-independence malaise. Brazil provides a valuable mirror to South Africa’s plight since it rose and fell for many of the same reasons and experienced similarly high levels of violence without armed groups and separatist movements. To take a step back, Brazil, like South Africa, fell victim to authoritarian rule during the Cold War. The South American nation suffered under a military junta characterized by anti-leftist purges for three decades. The junta’s complicity in Operation Condor paralleled the level of state-sanctioned violence in Apartheid-era South Africa. In 1985, after months of nationwide protests demanding free and fair elections and transparency, the junta collapsed. The election of Tancredo Neves as the first post-junta President typified a period of optimism and flourishing democracy foretelling the election of Nelson Mandela a decade later. Now, over three decades later, Brazil is racked with corruption, ineffective political leadership, and widespread criminality. Anti-corruption campaigns, such as Operation Car Wash, have exposed graft at all levels of government and civil society. Political tensions reached a boiling point when supporters loyal to ex-President Jair Bolsonaro, repeating lies of a ‘stolen election’, attacked the Brazilian federal government buildings in an episode reminiscent of the US Capital Attack on January 6, 2021. Thus, the nexus of those events and more have led Brazilian academics and foreign pundits alike to consider their country a ‘failing’ state. The amalgamation of its unfulfilled potential and domestic strife, all exacerbated by Jair Bolsonaro’s divisive Presidency, have led these defeatist perspectives to enter mainstream political and academic dialogues. The 2023 Brazilian Congress Attacks displayed how many Brazilians are becoming increasingly disillusioned with the government. Most poignant is the creation of a vicious cycle reinforcing fragility and thus the “Embattled State” perception, a credibility crisis. While Brazil does not face the same structural security and governance pitfalls failed states suffer from, the dissonance between its once lauded potential and reality pushes the nation into the ‘Embattled’ state discussion. Through the ‘Embattled State’ thesis, Brazil’s decline mirrors that of South Africa: public perceptions of failure dovetailing political decline.

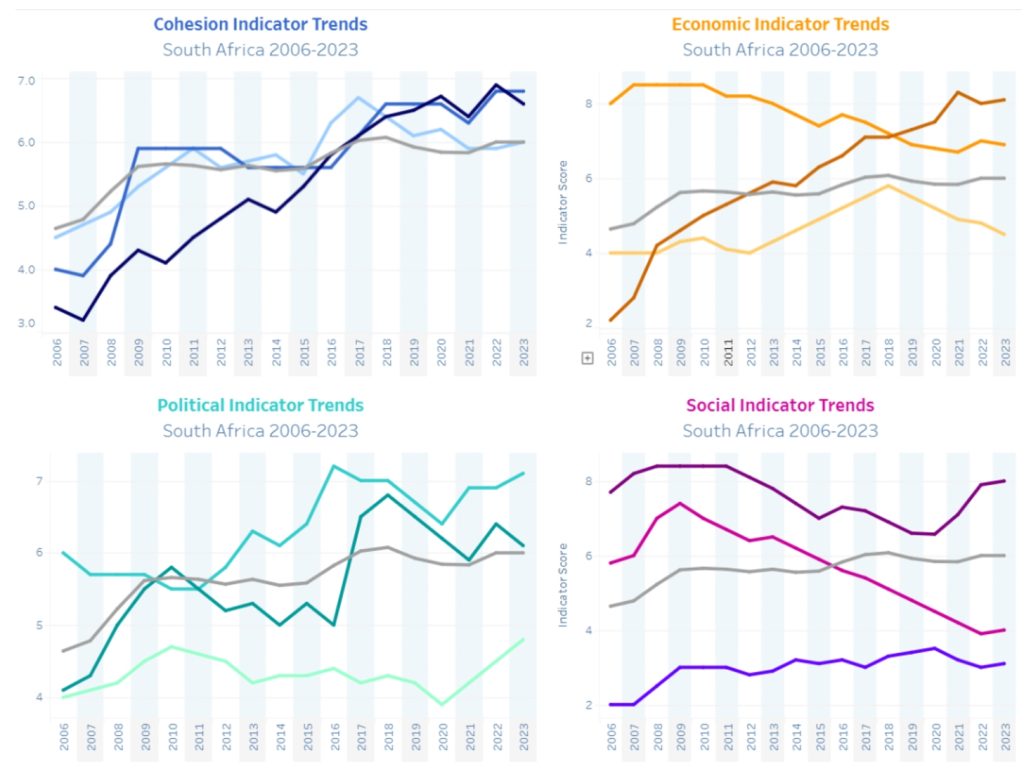

South Africa’s “dream deferred” is rooted in the consequences of Apartheid rule and economic discrimination. Those consequences have magnified since Mandela left office in 1999. Now, a confluence of malign economic factors including wealth concentration, income inequality, and corruption multiply the challenges facing the “rainbow nation’s” democratic and economic development. Specifically, a massive concentration of wealth, lack of investment in human capital, and general mismanagement of the economic structures led South Africa to weaken and thereby expose structural fissures. The 2023 Fragile States Index illustrates these cross-sector stresses in its portrayal of fragility across Cohesion, Economic, Political, and Social indicators.

Within the Cohesion indicator (top left), Factionalized Elites (C2) and the Security Apparatus (C1) indexes remain perpetually high. Neither has dropped below 6.0 since 2016. The implications of this trend are profound: they signal a country becoming increasingly disunited and insecure about its future. Additionally, steady increases in the Group Grievance (C3) and Demographic Pressure (S1) metrics signal rising racial and/or ethnic tensions. The motif of increased cross-sector fragility is reinforced in the indicator (top right). Despite experiencing a steady decrease since 2014 (8.8), Economic Inequality (E2) remains considerably high (6.9). Persistent rises in the Political Indicator Trends indicate South Africa is grappling with legitimacy and administrative stresses and mitigating neither. Fragility has gradually worsened in the Public Services (P2) and Human Rights (P3) metrics since 2019. These indicators describe growing dissatisfaction, pessimism, and the regime’s inability to balance crises at home. Given its state of erosion and defeatist perceptions, South Africa should be considered an “Embattled” state since it possesses characteristics of fragility and collapse to complement a bleak public narrative that is quite damning. As such, in May 2023, the Secretary General of the ANC, Fikile Mbalula lamented, “If certain things are not resolved, we will become a failed state.”

In addition to the fallout from Apartheid, Mandela’s immediate successors, Thabo Mbeki and Kgaleme Motlanthe, struggled to implement the vision underscoring the “Powerhouse of Africa” dream. Their tenures were bedeviled by mismanagement and corruption. Perhaps most damaging was Mbeki’s botched response to the HIV/AIDS Pandemic. Mbeki was very reluctant to employ Western medical means to combat the Pandemic, instead promoting traditional and unproven methods such as healers. The most poignant results were the deaths of 343,000 South Africans and deep distrust between the populace and the government. Mismanagement transcended the healthcare sector. Several of Mandela’s promises were at odds with the racist economic models and infrastructure inherited from the Apartheid regime. While well-intended and technocratic, in practice the Black Economic Empowerment Policy (BEE) exacerbated inequality for the millions that depended on it. The policy had a knock-on effect of aggrandizing a small cadre of elites which in turn accelerated corruption. James Vandrau of the University of Saint Andrews Law Faculty reflected, “Despite modest strides forward, considerable obstacles remain, including the rampant cronyism, nepotism and overarching malpolitics (sic) that has pervaded the program.” Inadequately combating the HIV/AIDS Pandemic and the consequences of ”staying the course” with the BEE heightened inequality and further tarnished the ANC’s legitimacy as a viable solution to the most pressing crises. The main byproducts of both of those policies were an augmented distrust between the populace and the regime and a dramatic decrease in foreign direct investment. The seeds for today’s “Embattled” state were laid.

While Mbeki and Molthanthe are responsible for much of the crisis, the lion’s share of culpability rests on Jacob Zuma. Zuma, often compared to Donald Trump, presided over what The Economist dubbed a “mountain of sleaze.” Zuma’s government enflamed tensions between the ANC and opposition groups, deepened corruption, ruled through patronage, and destroyed the ANC’s legitimacy. A paragon of Zuma’s mismanagement is his complicity in the Thales Group imbroglio. Zuma accepted roughly $34,000 in bribes from Thales in exchange for his pledge to protect the firm from an investigation into the $2 billion contract he negotiated as Deputy President. Considerable sums from the $2 billion contract later disappeared when Zuma ascended to the Presidency. This scandal was only the tip of the iceberg.

During the Zuma presidency, unemployment, crime, and violence soared. After his removal in 2018, many pundits lamented Zuma’s government as “having resembled an organized crime gang” and responsible for the “lost decade.” In essence, the vision of a ”Rainbow” nation and ”powerhouse of Africa” dreams rested on the foundation that South Africa had overcome its past, and forward-looking leaders would be responsible stewards in the democratization and economic development processes. However, both Mandela’s grandiose pledges and his successors’ direct and indirect mismanagement of his vision set the “rainbow nation” on a course destined for the “Embattled” state.

Despite the election of Cyril Ramaphosa in 2018, the country is yet to show signs of recovery. Zuma’s specter still haunts South African political society as the ANC struggles with infighting between supporters of the ousted president and Ramaphosa. Fears of the ANC splitting into two, three, or more parties are becoming more apparent when leaders seek to find novel ways to cultivate credibility and legitimacy in the eyes of the public. Divided and unable to target the most pressing issues, today’s “Embattled” state may only spiral further toward a failed state. Brian Levy, a contributor to The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, reports that Cyril Ramaphosa’s presidency “Has not been able to move decisively beyond a promise to stop the rot… the country’s deep-seated, underlying challenges remain, exacerbated by the economic consequences of the Coronavirus pandemic.” The sheer scale of the crisis will likely take at least a generation, if not more, of good governance to resuscitate the ”Rainbow Nation” and reignite the ”Powerhouse of Africa” vision. Due to pronounced cross-sector decay coupled with a tangible loss of public confidence in the ANC and democracy itself, it is becoming increasingly clear that the “Embattled” state is here to stay.

A curated seletion of FA’s must-read stories.

Written By: SHAGNIK BARMAN

Written By: BERK TUTTUP

Written By: ABBY L’BERT

Written By: BILLY AGWANDA

Written By: HIRA SARWAR

Written By: BATUHAN GUNES

Written By: LEON REED

Written By: DARSHAN GAJJAR

Alexander Bergh is a Master's student at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). He earned his Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Denver's Josef Korbel School of International Studies. Bergh previously worked for the US Defense Department's War Colleges and the Department of Health and Human Services in addition to two prominent American think tanks. From these industry and academic experiences, his main areas of study lie in American foreign policy, peace and conflict studies, and international security.

Written By: GABRIEL RAMIREZ

Written By: DILARA SAHIN

Written By: DILRUBA YILMAZ

Written By: NILAY CELIK

Written By: ELDANIZ GUSSEINOV

Written By: JOSEF SCHOEFL

Written By: SELCAN BEDIRHANOGLU

Written By: FATIH CEYLAN

FA’s flagship evening newsletter guilding you through the most important world streis ofthe day. Delivered weekdays.