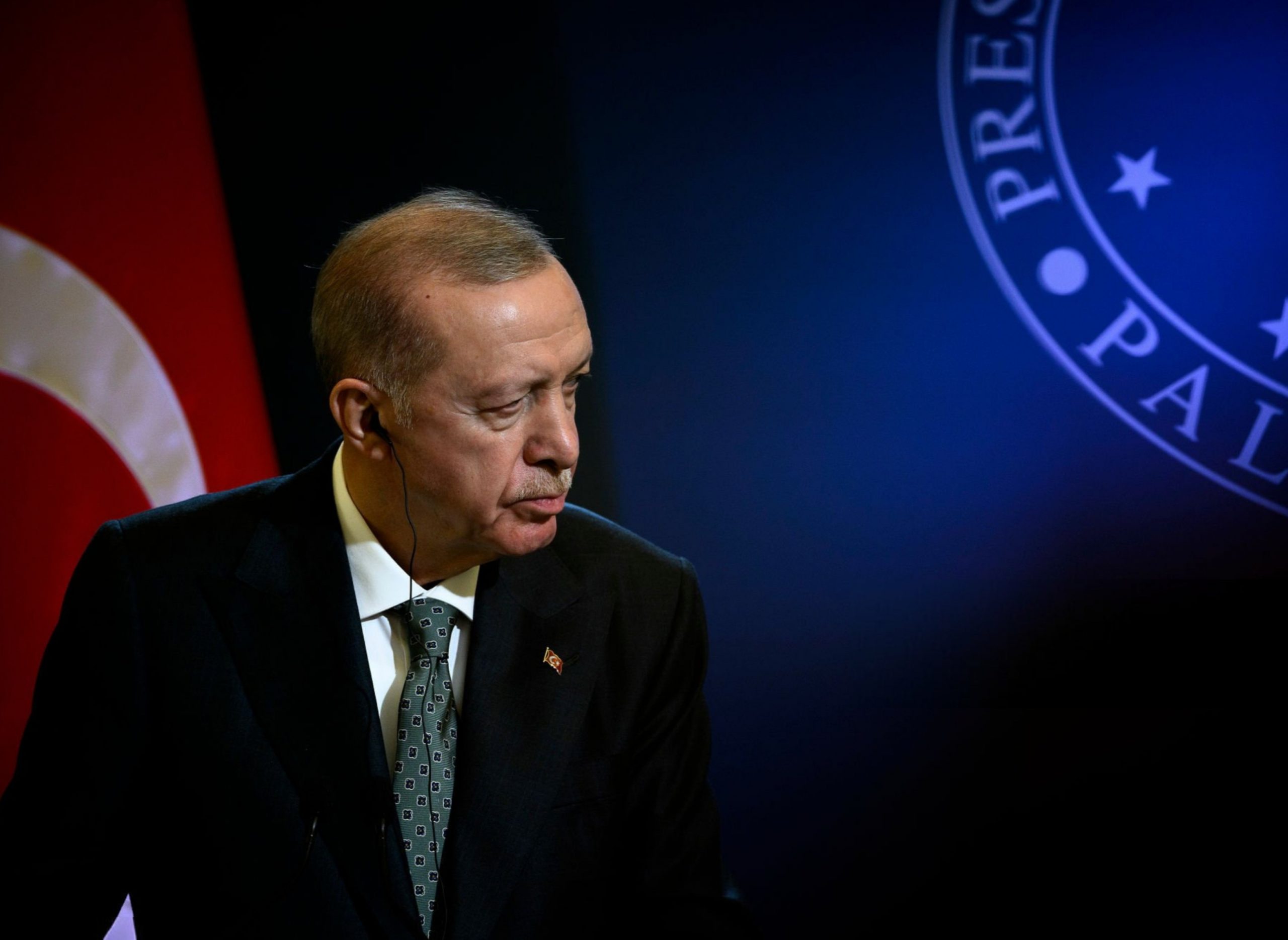

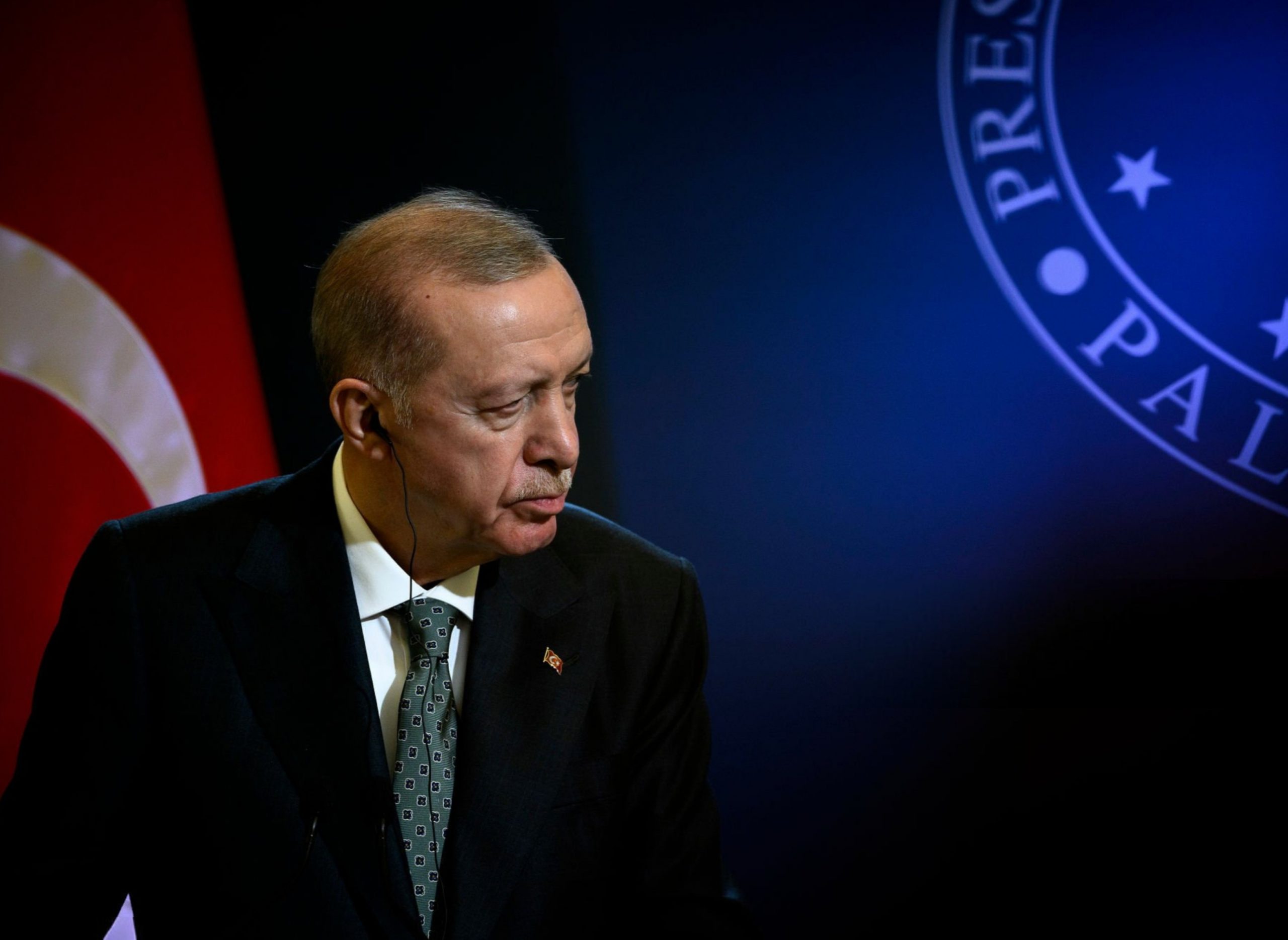

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni (not in picture) attend the press conference following their meeting at Villa Doria Pamphilj, on April 29, 2025 in Rome, Italy. (Photo by Antonio Masiello/Getty Images)

If we have to remember a date in the intricate world of geopolitics very recently, December 2024 could be the one. The sudden fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime following the resignation of the Butcher of Damascus on December 8th took many international observers, as well as Syrians themselves, by surprise. Indeed, for years, most specialists and media outlets analyzed the situation in Syria with great astonishment, observing the survival of the Assad regime despite the devastating civil war that had been ongoing since 2011. Most believed that the Syrian opposition and the West had missed their shot at overthrowing the “Lion” back in 2012. Most analysts expected the conflict to drag on for years, with the regime showing remarkable resilience against both internal and external opposition. Yet, here we are today, already beginning to describe Assad’s surprising fall. The once Arab Spring survivor is now gone and was overthrown in only a few weeks after years of bloody resistance at the head of Syria.

The opposition forces, led by the Islamists of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), launched a well-coordinated offensive at the end of November 2024, seizing Aleppo on November 29th, followed by Hama on December 5th and Homs on December 8th, opening the way to Damascus. But was this sudden regime change a real surprise? Not really. In fact, it seems that many signs were indicating the regime’s weakness, and moreover, the numerous changes in the regional context suggested that Assad’s grip over Syria was at risk. For some context, we will now briefly examine some of the key factors that may have led to the downfall of five decades of Baath rule over Syria.

First, it is important to remember how Syria is ethnically and religiously split, often aligning with long-standing political divisions, adding to the very fractured nature of the country. Indeed, all of these divisions were exacerbated by years of civil war, territorial partitions, and a long economic crisis, which had profoundly weakened Assad’s support base. The military, primarily composed of conscripts, also began to falter, with reports of soldiers fleeing their posts and abandoning the fight. This internal erosion was further compounded by a significant loss of public support, particularly among the Alawite community (making up most of the regime loyalist forces), which had traditionally been loyal to Assad.

On the other hand, the situation of the regime increasingly worsened with the rise of regional tensions, influenced by the war in Ukraine and the October 7th event. Russia had been a prominent supporter of the regime, backing up its forces on the ground, but the Russian invasion of Ukraine starting in February 2022 forced Moscow to considerably withdraw its forces from Syria and lighten its presence in the country. The events following October 7th also had a major impact on Syria. With the Israeli incursion in South Lebanon and the weakening of Hezbollah, an Iranian-backed Shia proxy, the Baath regime lost one of its major allies in controlling the Assad-ruled territory. All of these events had probably played a major role in weakening the regime, prophesying the fall of Damascus.

Finally, the mortal blow came with the offensive led by HTS and its leader, Ahmed al-Sharaa (also known as Abu Mohammad al-Julani), in November 2024. Their ability to mobilize and capitalize on Assad’s military fatigue and the defection of regime forces truly played a crucial role in the rapid disintegration of Assad’s control. Furthermore, the population’s massive hatred towards the regime, now only supported by the Alawite minority, facilitated the rebels’ successful offensive.

Behind Assad’s Collapse

But another factor played a huge role in the fall of the Assad regime in Syria: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s unwavering support for the rebels, without which nothing could have happened. For some, such support did not come out of nowhere, with the hostility between Ankara and Damascus being ancient. However, things could have gone a different way, as Erdogan tried to reconcile with Bashar al-Assad many times in recent years, seeking to facilitate the repatriation of millions of Syrian refugees and to ease growing domestic discontent within Türkiye. Yet this attempt at reconciliation remained a dead letter, as Assad rejected all overtures and demanded a complete Turkish military withdrawal from northern Syria as a prerequisite for reconciliation. Probably frustrated at such a diplomatic deadlock, Erdogan finally decided to revert to the traditional Turkish hostility towards the Baath regime and thus intensified Türkiye’s partnership with Syrian rebel factions, such as HTS.

holding a Master’s degree in International Relations from the American University School of International Service. His research focuses on global governance, international politics, political economy, and Middle Eastern affairs.

If we have to remember a date in the intricate world of geopolitics very recently, December 2024 could be the one. The sudden fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime following the resignation of the Butcher of Damascus on December 8th took many international observers, as well as Syrians themselves, by surprise. Indeed, for years, most specialists and media outlets analyzed the situation in Syria with great astonishment, observing the survival of the Assad regime despite the devastating civil war that had been ongoing since 2011. Most believed that the Syrian opposition and the West had missed their shot at overthrowing the “Lion” back in 2012. Most analysts expected the conflict to drag on for years, with the regime showing remarkable resilience against both internal and external opposition. Yet, here we are today, already beginning to describe Assad’s surprising fall. The once Arab Spring survivor is now gone and was overthrown in only a few weeks after years of bloody resistance at the head of Syria.

The opposition forces, led by the Islamists of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), launched a well-coordinated offensive at the end of November 2024, seizing Aleppo on November 29th, followed by Hama on December 5th and Homs on December 8th, opening the way to Damascus. But was this sudden regime change a real surprise? Not really. In fact, it seems that many signs were indicating the regime’s weakness, and moreover, the numerous changes in the regional context suggested that Assad’s grip over Syria was at risk. For some context, we will now briefly examine some of the key factors that may have led to the downfall of five decades of Baath rule over Syria.

First, it is important to remember how Syria is ethnically and religiously split, often aligning with long-standing political divisions, adding to the very fractured nature of the country. Indeed, all of these divisions were exacerbated by years of civil war, territorial partitions, and a long economic crisis, which had profoundly weakened Assad’s support base. The military, primarily composed of conscripts, also began to falter, with reports of soldiers fleeing their posts and abandoning the fight. This internal erosion was further compounded by a significant loss of public support, particularly among the Alawite community (making up most of the regime loyalist forces), which had traditionally been loyal to Assad.

On the other hand, the situation of the regime increasingly worsened with the rise of regional tensions, influenced by the war in Ukraine and the October 7th event. Russia had been a prominent supporter of the regime, backing up its forces on the ground, but the Russian invasion of Ukraine starting in February 2022 forced Moscow to considerably withdraw its forces from Syria and lighten its presence in the country. The events following October 7th also had a major impact on Syria. With the Israeli incursion in South Lebanon and the weakening of Hezbollah, an Iranian-backed Shia proxy, the Baath regime lost one of its major allies in controlling the Assad-ruled territory. All of these events had probably played a major role in weakening the regime, prophesying the fall of Damascus.

Finally, the mortal blow came with the offensive led by HTS and its leader, Ahmed al-Sharaa (also known as Abu Mohammad al-Julani), in November 2024. Their ability to mobilize and capitalize on Assad’s military fatigue and the defection of regime forces truly played a crucial role in the rapid disintegration of Assad’s control. Furthermore, the population’s massive hatred towards the regime, now only supported by the Alawite minority, facilitated the rebels’ successful offensive.

Behind Assad’s Collapse

But another factor played a huge role in the fall of the Assad regime in Syria: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s unwavering support for the rebels, without which nothing could have happened. For some, such support did not come out of nowhere, with the hostility between Ankara and Damascus being ancient. However, things could have gone a different way, as Erdogan tried to reconcile with Bashar al-Assad many times in recent years, seeking to facilitate the repatriation of millions of Syrian refugees and to ease growing domestic discontent within Türkiye. Yet this attempt at reconciliation remained a dead letter, as Assad rejected all overtures and demanded a complete Turkish military withdrawal from northern Syria as a prerequisite for reconciliation. Probably frustrated at such a diplomatic deadlock, Erdogan finally decided to revert to the traditional Turkish hostility towards the Baath regime and thus intensified Türkiye’s partnership with Syrian rebel factions, such as HTS.

holding a Master’s degree in International Relations from the American University School of International Service. His research focuses on global governance, international politics, political economy, and Middle Eastern affairs.

In general, one should realize one thing: Türkiye has always been a key external player in the Syrian civil war from the very beginning, using its border proximity to provide material and logistical support to opposition groups seeking to topple Assad. Already accused by many external observers of hidden support to the so-called Islamic State, Türkiye has in reality always been a supporter of diverse rebel groups, such as the Free Syrian Army, but also, to a lesser extent, HTS. Such support must be examined in the light of Ankara’s long-standing goal in Syria: first, preventing the establishment of an autonomous entity in northern Syria under Kurdish authority, as Türkiye would perceive such an entity as an existential security threat; and second, to shape a post-Assad Syria in a manner that serves its strategic interests, notably by securing Türkiye’s dominant role in the country’s reconstruction. Thereby, the November offensive led by HTS and its allies provided Erdogan with an unprecedented opportunity to fulfill these objectives.

According to most observers and experts, it is very likely that Türkiye was at first planning on delaying HTS’s offensive, only supporting an extension of the HTS-controlled area around Idlib. Indeed, it seems that Erdogan initially preferred a negotiated settlement with Assad. However, the initial loss of Turkish support to what was supposed to be a light offensive aiming at threatening Assad ended up with a power switch and the fall of Assad’s rule over Syria. As explained above, Ankara ultimately allowed the group to proceed further when Moscow failed to restrain Assad’s aggression in Idlib.

But is this regime switch in Damascus a “victory” for Erdogan? Could he frame this as a political or strategic win? At first glance, many would be tempted to respond to such a question affirmatively, as the collapse of Assad’s regime appears to be a geopolitical victory for Türkiye in many aspects. In fact, Erdogan’s years of support towards opposition factions look to have paid off, and Ankara now holds significant leverage in shaping Syria’s political future. As proof, the fall of Assad has been celebrated by large segments of the Turkish population, particularly among the millions of Syrian refugees living in Türkiye and eager to return home. However, Erdogan’s triumph is very far from being absolute. While it is true that the Turkish backing of opposition groups played a role in Assad’s downfall, Türkiye did not entirely dictate the course of events, and HTS’s unexpected level of success has probably introduced new uncertainties for Ankara.

Hence, the answer to the above question is certainly not as straightforward as people would think. Türkiye has certainly achieved key strategic objectives: the removal of Assad, the weakening of Kurdish forces, and an expanded role in Syria’s future. Yet, Ankara has also inherited significant challenges. As this article will explore, Türkiye’s position in post-Assad Syria is very complex and must be closely analyzed before concluding on Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s absolute victory in Syria.

Influence, But Not Command

When it comes to Türkiye’s position in the region, things seem to be going pretty well for Erdogan’s diplomacy. In this new post-Assad era, Türkiye certainly holds a unique position to influence Syria’s reconstruction and political future. Indeed, Ankara’s proximity to the rebels and its long-standing support for opposition groups place it in a dominant role, with many specialists agreeing that HTS’s success greatly depended on Erdogan’s support, who likely gave the green light for the November offensive, which ultimately overthrew the “Butcher of Damascus.” With the fall of the Assad dynasty, Türkiye’s hands are now free to facilitate the return of millions of Syrian refugees and assert its control over the majority Kurdish regions in the north, notably by countering the influence of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and preventing the establishment of a Kurdish autonomous entity in Rojava.

In general, one should realize one thing: Türkiye has always been a key external player in the Syrian civil war from the very beginning, using its border proximity to provide material and logistical support to opposition groups seeking to topple Assad. Already accused by many external observers of hidden support to the so-called Islamic State, Türkiye has in reality always been a supporter of diverse rebel groups, such as the Free Syrian Army, but also, to a lesser extent, HTS. Such support must be examined in the light of Ankara’s long-standing goal in Syria: first, preventing the establishment of an autonomous entity in northern Syria under Kurdish authority, as Türkiye would perceive such an entity as an existential security threat; and second, to shape a post-Assad Syria in a manner that serves its strategic interests, notably by securing Türkiye’s dominant role in the country’s reconstruction. Thereby, the November offensive led by HTS and its allies provided Erdogan with an unprecedented opportunity to fulfill these objectives.

According to most observers and experts, it is very likely that Türkiye was at first planning on delaying HTS’s offensive, only supporting an extension of the HTS-controlled area around Idlib. Indeed, it seems that Erdogan initially preferred a negotiated settlement with Assad. However, the initial loss of Turkish support to what was supposed to be a light offensive aiming at threatening Assad ended up with a power switch and the fall of Assad’s rule over Syria. As explained above, Ankara ultimately allowed the group to proceed further when Moscow failed to restrain Assad’s aggression in Idlib.

But is this regime switch in Damascus a “victory” for Erdogan? Could he frame this as a political or strategic win? At first glance, many would be tempted to respond to such a question affirmatively, as the collapse of Assad’s regime appears to be a geopolitical victory for Türkiye in many aspects. In fact, Erdogan’s years of support towards opposition factions look to have paid off, and Ankara now holds significant leverage in shaping Syria’s political future. As proof, the fall of Assad has been celebrated by large segments of the Turkish population, particularly among the millions of Syrian refugees living in Türkiye and eager to return home. However, Erdogan’s triumph is very far from being absolute. While it is true that the Turkish backing of opposition groups played a role in Assad’s downfall, Türkiye did not entirely dictate the course of events, and HTS’s unexpected level of success has probably introduced new uncertainties for Ankara.

Hence, the answer to the above question is certainly not as straightforward as people would think. Türkiye has certainly achieved key strategic objectives: the removal of Assad, the weakening of Kurdish forces, and an expanded role in Syria’s future. Yet, Ankara has also inherited significant challenges. As this article will explore, Türkiye’s position in post-Assad Syria is very complex and must be closely analyzed before concluding on Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s absolute victory in Syria.

Influence, But Not Command

When it comes to Türkiye’s position in the region, things seem to be going pretty well for Erdogan’s diplomacy. In this new post-Assad era, Türkiye certainly holds a unique position to influence Syria’s reconstruction and political future. Indeed, Ankara’s proximity to the rebels and its long-standing support for opposition groups place it in a dominant role, with many specialists agreeing that HTS’s success greatly depended on Erdogan’s support, who likely gave the green light for the November offensive, which ultimately overthrew the “Butcher of Damascus.” With the fall of the Assad dynasty, Türkiye’s hands are now free to facilitate the return of millions of Syrian refugees and assert its control over the majority Kurdish regions in the north, notably by countering the influence of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and preventing the establishment of a Kurdish autonomous entity in Rojava.

Moreover, with Russia and Iran both experiencing significant setbacks in Syria, Türkiye seems to have emerged as the most influential foreign power in the post-Assad environment. Russia, distracted by its conflict in Ukraine and unable to intervene effectively in Syria’s rapid power shift, and Iran, whose inability to provide decisive support to Assad led to his downfall, have both seen their influence wane. On the other hand, Türkiye, initially cautious about HTS’s rise, has now managed to secure key advantages in Syria, positioning itself as a dominant actor moving forward, as pointed out by many experts. So, is Türkiye’s influence in this new Syrian configuration absolute? Things may not be as easy. Indeed, Türkiye’s position in Syria remains fragile, as its influence could be tempered by the rising prominence of HTS, whose dependence on Erdogan’s support has diminished since the Islamist group took control of Damascus.

As pointed out by the Council on Foreign Relations, HTS maintains rather pragmatic cooperation with Ankara, operating independently, and is not directly controlled by Türkiye, as are other rebel groups, such as the Syrian National Army (SNA), with HTS even manufacturing its own arms. Another obstacle is Türkiye’s diplomatic ability to sustain its influence in a very fractured Syrian political landscape. HTS’s role complicates Türkiye’s ability to shape Syria’s future, as it seeks a balance between engaging with the group led by Ahmed al-Sharaa and maintaining its broader goals. Furthermore, the potential emergence of a new, stronger Syrian government will likely challenge Türkiye’s influence, especially if the new leadership becomes more independent or resistant to Turkish involvement, particularly regarding the future reconstruction and political restructuring of the country. As pointed out previously, HTS’s dependence on Erdogan’s support has diminished, and what used to be a rather marginalized group now enjoys broad popular support among Syrians as well as international benevolence.

Friends Turned Foes

But what about the other regional actors – and possibly competitors to Türkiye’s influence? Very surprisingly, yesterday’s friends have become today’s enemies. Indeed, foreign powers who supported Assad’s regime now find themselves on the other side of the Rubicon, namely, Russia and Iran. Continuing the long-lasting Soviet friendship with the Assads, Russia has been a key player in the Syrian civil war, saving the regime both politically—notably at the UN by hampering numerous UN peacekeeping missions—and, of course, militarily by sustaining Assad’s power on the ground. Yet, the Kremlin, which used Syria as a strategic foothold in the Eastern Mediterranean, now faces the possibility of losing its military base in Tartous and its influence over the Syrian government.

Similarly, the Iranian godfather has also lost most of its influence in Syria since the fall of Assad. Syria had always been the masterpiece of the Iranian strategy in the Middle East as part of its Shia axis, Assad being used as an Iranian proxy to secure its influence in the Levant and serving as a corridor to Hezbollah in Lebanon. Leveraging its military power through Hezbollah, the Iranian alliance used to be crucial in maintaining Assad in power as well. However, the fall of the Assad regime and its replacement at the head of Syria by a Sunni Muslim group hostile to the Iranian presence has certainly annihilated Tehran’s influence for good. Whatever their roles in Syrian contemporary history, neither Russia nor Iran intervened decisively as Assad’s regime crumbled, signaling either a strategic retreat or an inability to support the Syrian government.

For the Western powers, things are less clear. The U.S. is in historical support of the Kurdish forces in northern Syria, notably backing up the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) as part of its broader strategy against ISIS. With Assad’s regime ousted, the U.S. and European powers will need to recalibrate their strategies. Although the U.S. remains committed to countering ISIS and its resurgence, the collapse of Assad’s government could see a shift in U.S. foreign policy, with the choice of either supporting the new leadership in Damascus or focusing on stabilizing northern Syria. The future of the SDF will be crucial here, as the U.S. faces increased pressure from Türkiye to abandon support for Kurdish groups, which Ankara views as terrorist affiliates of the PKK. Much like Türkiye, some European countries such as Germany or Sweden have been hosting millions of Syrian refugees since 2012 and could then opt for a rapprochement with this new Syrian regime to facilitate their repatriation. Moreover, Europeans are generally interested in stabilizing the region and have always been fierce opponents of Assad, which could also foster a new dynamic in European-Syrian relations.

Post-Assad Syria resembles less a strategic playground and more a political minefield.

The role of Gulf states, particularly Saudi Arabia and Qatar, will be pivotal in shaping Syria’s future. This is also true for the new government in Damascus, whose capacity to attract funds from Gulf countries will be crucial to finance the reconstruction of the country. Saudi Arabia traditionally seeks to limit Iranian influence in the region and thus may align itself with Türkiye to fill the gap left by Tehran’s declining influence in Syria. Likewise, Qatar’s ideological proximity with the new power in Damascus and long-standing alliance with Erdogan might serve Doha’s interests in Syria and facilitate the securing of Qatari funds for the new regime. Hence, it can be argued that the fall of Assad has dramatically reshaped the regional power balance, with Türkiye emerging as a key beneficiary. However, the complexities introduced by HTS’s rise and the uncertain future of Syria’s political landscape pose challenges for Ankara’s long-term influence.

A Border Redrawn

In terms of gains, one should first observe the reduction—some would even speak about “elimination”—of the YPG threat. Türkiye has long viewed the Syrian Kurdish forces, and particularly the YPG, as an extension of the PKK, which Ankara labels as a terrorist organization and enemy number one of the Republic. For the new “Sultan” of Ankara, supporting rebel forces such as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and the Syrian National Army (SNA) is seen as a very practical step to eliminate Kurdish autonomy in northern Syria. Indeed, some consider that with the fall of the regime, as well as the recent election of Donald Trump in Washington, Erdogan is now freer than ever to seize the opportunity of achieving a strategic victory by eliminating Kurdish autonomy in northern Syria and preventing the Kurds from making the junction between the sides of the Syrian/Turkish border.

Moreover, Erdogan believes that the fall of the Baathist regime set the conditions for the return of millions of Syrian refugees living in Türkiye since the civil war. In fact, the Turkish president has set the return of Syrian refugees currently residing in Türkiye as one of his primary goals, especially in view of the upcoming elections in 2028, as the subject remains an important preoccupation among the population. Hence, the fall of Assad gives Türkiye an opportunity to stabilize Syria and create the necessary conditions for these refugees to feel safe and hopeful enough about the future economic conditions in Syria to return home. Moreover, it is clear that many Syrians have already started to return home, while others are seriously considering doing the same, proving the Turkish president a little more right.

Finally, Türkiye may find it easier to establish security zones along its border and strengthen its control over northern Syria with an allied regime being in place in Damascus for the first time since the fall of the Ottoman Empire. These zones are expected to provide greater protection against insurgent groups and Kurdish fighters. Hence, the securitization of its southern border, rid of the presence of a hostile regime in Damascus, can be seen as one of the greatest achievements of this regime change for Türkiye, further contributing to its national security—something that the president can claim as a political benefit for Erdogan.

The Syrian Bill

However, the picture is not entirely rosy either, and the fall of the Baathist regime in Damascus could lead to further destabilization of the country after a few years of relative calm, thus negatively impacting Türkiye. In general, it would be wiser for Erdogan to also expect a downside behind this apparent victory. So, first, let us talk numbers—not the kind politicians throw around in press briefings, but the kind that quietly bleed through national budgets and haunt long-term strategy. Syria’s reconstruction is not going to come cheap. And guess who is footing part of the bill? Türkiye. Türkiye is not just a neighbor peering over the fence; it is hosting millions of Syrian refugees, and like it or not, that places it squarely in the reconstruction hot seat.

Ankara has already signaled a willingness to help rebuild its war-ravaged neighbor—cue Erdogan’s latest diplomatic overtures—but this is more than a goodwill gesture. It is a high-stakes balancing act. Supporting infrastructure, managing the logistics of refugee return, and fostering sustainable development in the volatile northern regions? That is not a weekend project—it is a generational one. And make no mistake, it will test both Türkiye’s wallet and its political stamina. Rebuilding Syria may also mean rebuilding trust. Or, more likely, bracing for a cold diplomatic standoff. Türkiye has played a long game in Syria, backing opposition forces and carving out influence zones, especially in Idlib. But the political terrain is shifting fast. HTS’s growing prominence, coupled with the emergence of a potentially less Türkiye-friendly government in Damascus, could spell trouble. A Syria that is more autonomous—and less receptive to Ankara’s military footprint or its alliances with rebel groups—could ignite diplomatic tensions that are anything but theoretical.

Let us not forget: Türkiye is not the only power eyeing a post-Assad Syria. The U.S. is still firmly in play, backing Kurdish forces in the north—forces Ankara sees as a threat wrapped in a flag. And the Gulf monarchies? They may have their own plans, their own checkbooks, and perhaps their own preferred partners in Damascus. If Riyadh or Doha start cozying up to the new Syrian leadership, Türkiye’s regional strategy could quickly feel more like a solo than a symphony. So, Türkiye may dream of a secure southern border, a weakened Kurdish push for autonomy, and a streamlined refugee return. But dreams come with invoices. Between the steep costs of reconstruction, rising friction with Damascus, and geopolitical elbowing from the U.S. and Gulf players, Ankara’s post-Assad playbook is anything but straightforward. This is not just a question of whether Türkiye can win influence in Syria, but whether it can afford the price tag.

Ankara’s Fragile Leverage

Now that the dust is settling in Damascus and HTS’s black-and-white banners have been hastily swapped for tailored suits and diplomatic jargon, Ankara is finding itself in an increasingly ambiguous dance with Syria’s new leadership. On paper, Erdogan should be basking in vindication—after all, Türkiye’s long bet on the opposition has paid off. However, beneath the surface, the situation is far more complex. While Türkiye has undoubtedly been instrumental in shaping the post-Assad order, notably by supporting the rebel coalition that led the charge to Damascus, it does not fully control the monster it helped create.

HTS and its leader, Ahmad al-Sharaa (who now presides over Syria’s transition government), were once officially branded a terrorist group by Ankara itself. Now, a fragile, pragmatic cooperation binds the two: a relationship defined more by tactical alignment than ideological harmony. Still, Türkiye has not given up its ambitions to mold the new Syria. Turkish officials, including Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan, have wasted no time swooping into Damascus with grand offers: military training, reconstruction funds, and even help building a new national army.

These overtures, however, come with clear strings attached—namely, the expectation that the new regime clamps down on Kurdish autonomy and keeps Ankara’s interests front and center. Idlib remains a sticking point. Türkiye’s military footprint there is not only symbolic but strategic. The area has long served as a buffer zone against Kurdish forces and Assad loyalists alike. But as the new Syrian leadership consolidates power, questions arise: Will Ankara’s presence be tolerated as a necessary security umbrella or resented as foreign meddling? As El País reported, Türkiye’s sprawling network of intelligence, police, and media in Syria’s capital may feel more like occupation than cooperation to some within HTS’s orbit.

And therein lies the rub: HTS is not the Syrian National Army. It is not built to be Türkiye’s puppet. As Chatham House cautions, Ankara’s newfound leverage comes with equally weighty responsibilities and potential blowback. HTS may grow increasingly assertive, its leaders emboldened by popular support and their newfound legitimacy. If the governance style in Damascus begins to diverge too far from Ankara’s preferences—such as veering too Islamist or too independent—friction is inevitable. So, is Türkiye the new kingmaker in Syria? Perhaps. But if Erdogan hoped for a pliable ally in Damascus, he may find himself instead navigating a precarious alliance with a regime that owes him gratitude, but not obedience. And in Middle Eastern politics, that distinction makes all the difference.

Erdoğan’s Grand Narrative

For Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the fall of Assad is more than a geopolitical trophy; it is a golden political script, handed to him just in time for the next domestic chapter. In classic Erdogan fashion, the narrative is already being spun: Türkiye stood firm, played the long game, and emerged with moral authority and regional leverage. And now? Now comes the payback at home. As Dareen Khalifa from The Guardian notes, Ankara is walking a “victory lap,” with Turkish officials promptly planting their flag over the reopened embassy in Damascus just days after Assad’s departure. This is why the Turkish intelligence chief, Ibrahim Kalin’s high-profile visit can be seen as the first signal that Erdogan intends to capitalize on the moment to its fullest extent.

Moreover, with Russia and Iran both experiencing significant setbacks in Syria, Türkiye seems to have emerged as the most influential foreign power in the post-Assad environment. Russia, distracted by its conflict in Ukraine and unable to intervene effectively in Syria’s rapid power shift, and Iran, whose inability to provide decisive support to Assad led to his downfall, have both seen their influence wane. On the other hand, Türkiye, initially cautious about HTS’s rise, has now managed to secure key advantages in Syria, positioning itself as a dominant actor moving forward, as pointed out by many experts. So, is Türkiye’s influence in this new Syrian configuration absolute? Things may not be as easy. Indeed, Türkiye’s position in Syria remains fragile, as its influence could be tempered by the rising prominence of HTS, whose dependence on Erdogan’s support has diminished since the Islamist group took control of Damascus.

As pointed out by the Council on Foreign Relations, HTS maintains rather pragmatic cooperation with Ankara, operating independently, and is not directly controlled by Türkiye, as are other rebel groups, such as the Syrian National Army (SNA), with HTS even manufacturing its own arms. Another obstacle is Türkiye’s diplomatic ability to sustain its influence in a very fractured Syrian political landscape. HTS’s role complicates Türkiye’s ability to shape Syria’s future, as it seeks a balance between engaging with the group led by Ahmed al-Sharaa and maintaining its broader goals. Furthermore, the potential emergence of a new, stronger Syrian government will likely challenge Türkiye’s influence, especially if the new leadership becomes more independent or resistant to Turkish involvement, particularly regarding the future reconstruction and political restructuring of the country. As pointed out previously, HTS’s dependence on Erdogan’s support has diminished, and what used to be a rather marginalized group now enjoys broad popular support among Syrians as well as international benevolence.

Friends Turned Foes

But what about the other regional actors – and possibly competitors to Türkiye’s influence? Very surprisingly, yesterday’s friends have become today’s enemies. Indeed, foreign powers who supported Assad’s regime now find themselves on the other side of the Rubicon, namely, Russia and Iran. Continuing the long-lasting Soviet friendship with the Assads, Russia has been a key player in the Syrian civil war, saving the regime both politically—notably at the UN by hampering numerous UN peacekeeping missions—and, of course, militarily by sustaining Assad’s power on the ground. Yet, the Kremlin, which used Syria as a strategic foothold in the Eastern Mediterranean, now faces the possibility of losing its military base in Tartous and its influence over the Syrian government.

Similarly, the Iranian godfather has also lost most of its influence in Syria since the fall of Assad. Syria had always been the masterpiece of the Iranian strategy in the Middle East as part of its Shia axis, Assad being used as an Iranian proxy to secure its influence in the Levant and serving as a corridor to Hezbollah in Lebanon. Leveraging its military power through Hezbollah, the Iranian alliance used to be crucial in maintaining Assad in power as well. However, the fall of the Assad regime and its replacement at the head of Syria by a Sunni Muslim group hostile to the Iranian presence has certainly annihilated Tehran’s influence for good. Whatever their roles in Syrian contemporary history, neither Russia nor Iran intervened decisively as Assad’s regime crumbled, signaling either a strategic retreat or an inability to support the Syrian government.

For the Western powers, things are less clear. The U.S. is in historical support of the Kurdish forces in northern Syria, notably backing up the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) as part of its broader strategy against ISIS. With Assad’s regime ousted, the U.S. and European powers will need to recalibrate their strategies. Although the U.S. remains committed to countering ISIS and its resurgence, the collapse of Assad’s government could see a shift in U.S. foreign policy, with the choice of either supporting the new leadership in Damascus or focusing on stabilizing northern Syria. The future of the SDF will be crucial here, as the U.S. faces increased pressure from Türkiye to abandon support for Kurdish groups, which Ankara views as terrorist affiliates of the PKK. Much like Türkiye, some European countries such as Germany or Sweden have been hosting millions of Syrian refugees since 2012 and could then opt for a rapprochement with this new Syrian regime to facilitate their repatriation. Moreover, Europeans are generally interested in stabilizing the region and have always been fierce opponents of Assad, which could also foster a new dynamic in European-Syrian relations.

This is no small matter. With over 3.2 million Syrian refugees inside Turkish borders, Erdogan is threading the needle between his image as a protector of the ummah and his nationalist allies’ less charitable view of displaced Syrians. Now, with Syria inching toward stability, Erdogan can claim the moral high ground while quietly facilitating returns. His strategy is plain and simple: turning a political liability into a triumph. In this context, Assad’s downfall gives Erdogan the opportunity to “bolster his brand” as the leader who both sheltered Syrians and orchestrated their dignified return. Such an outcome would likely soothe domestic tensions while polishing his legacy.

And indeed, public opinion is watching closely. As Chatham House points out, Turks remain divided. While some may be wary of repatriation promises, others demand quicker returns amid economic woes. Erdogan understands this balancing act all too well. He is relying on the optics of diplomacy in Damascus and reconstruction in Syria to calm internal dissent, rally nationalist pride, and reinforce his message to voters. From his perspective, the strategy has succeeded against the odds: he played the regional game and won. But with every political win comes expectation. Now, he must deliver.

At the Table—or on It?

Now that Assad is finally out of the picture, the international stage surrounding Syria is being re-scripted. In this new context, Türkiye is not just rewriting its role but vying for top billing. While other regional powers scramble to recalibrate, Ankara has made its position unmistakably clear: this post-Assad Syria will be navigated on Turkish terms—or at least under heavy Turkish influence. As prophesied by Erdogan, his allies would one day pray in the courtyards of the Umayyad Mosque after Assad’s fall, and this vision now appears to be edging toward reality.

Kalin was recently spotted strolling through the streets of Damascus like a man surveying new real estate. Not particularly subtle, but certainly strategic. Türkiye’s clout in Syria is no accident; it is the result of a long game—a mixture of ideological ambition, hard power, and cold pragmatism. With HTS consolidating control and forming a provisional government, Türkiye is not only the dominant external actor in Syria but can arguably be seen as the broker of what comes next. Through a careful dance of cooperation and containment, Ankara has turned HTS from a terrorist-designated entity into a de facto gatekeeper: helping curb drug trafficking, controlling ISIS infiltration, and detaining those Ankara wants removed.

In this new chapter, the central question is how Türkiye will maneuver its relationships with the real titans of geopolitics, such as the U.S., Russia, and Iran. Moscow and Tehran come first. Their influence was tethered to Assad’s survival. With him gone, Ankara has seized the momentum. Russia, preoccupied and overstretched, is unlikely to reassert itself decisively in northern Syria. Iran, whose support for Damascus had always been more ideological than strategic, now finds itself sidelined—especially in Sunni-majority areas where Turkish-backed groups hold sway. And the United States? That relationship remains far more complicated.

Despite being NATO allies, Ankara and Washington remain deeply divided on the Kurdish question. The U.S. continues to support the SDF, whose backbone, the YPG, is anathema to Türkiye. Erdogan’s policy is unambiguous: dismantle any form of Kurdish autonomy near the southern border, with or without U.S. approval. With a planned U.S. withdrawal from Syria by 2026, Ankara senses opportunity. The departure of American forces may translate into increased Turkish influence—not just physically, but diplomatically, economically, and ideologically. In short, Syria’s power vacuum has become Türkiye’s geopolitical feast, and Erdogan is already carving out his preferred portions. Whether other global actors will find themselves at the table—or on the menu—remains to be seen.

Not the Endgame Yet

So, has Recep Tayyip Erdogan truly won in Syria? That depends on how “victory” is defined—and whose scoreboard is being used. If success is measured purely in geopolitical terms, Türkiye has clearly advanced several key positions on the chessboard: Assad is out, HTS is in (with Ankara’s tacit approval), and Turkish officials are already shaking hands in Damascus while planning border security zones. Not bad for a player once accused of overreach. However, if Erdogan was hoping for a pliable, pro-Türkiye government that would resolve the refugee crisis, eliminate Kurdish threats, and grant Ankara veto power over Syria’s future, it may be premature to declare “mission accomplished.”

The role of Gulf states, particularly Saudi Arabia and Qatar, will be pivotal in shaping Syria’s future. This is also true for the new government in Damascus, whose

capacity to attract funds from Gulf countries will be crucial to finance the reconstruction of the country. Saudi Arabia traditionally seeks to limit Iranian influence in the region and thus may align itself with Türkiye to fill the gap left by Tehran’s declining influence in Syria. Likewise, Qatar’s ideological proximity with the new power in Damascus and long-standing alliance with Erdogan might serve Doha’s interests in Syria and facilitate the securing of Qatari funds for the new regime. Hence, it can be argued that the fall of Assad has dramatically reshaped the regional power balance, with Türkiye emerging as a key beneficiary. However, the complexities introduced by HTS’s rise and the uncertain future of Syria’s political landscape pose challenges for Ankara’s long-term influence.

A Border Redrawn

In terms of gains, one should first observe the reduction—some would even speak about “elimination”—of the YPG threat. Türkiye has long viewed the Syrian Kurdish forces, and particularly the YPG, as an extension of the PKK, which Ankara labels as a terrorist organization and enemy number one of the Republic. For the new “Sultan” of Ankara, supporting rebel forces such as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and the Syrian National Army (SNA) is seen as a very practical step to eliminate Kurdish autonomy in northern Syria. Indeed, some consider that with the fall of the regime, as well as the recent election of Donald Trump in Washington, Erdogan is now freer than ever to seize the opportunity of achieving a strategic victory by eliminating Kurdish autonomy in northern Syria and preventing the Kurds from making the junction between the sides of the Syrian/Turkish border.

Moreover, Erdogan believes that the fall of the Baathist regime set the conditions for the return of millions of Syrian refugees living in Türkiye since the civil war. In fact, the Turkish president has set the return of Syrian refugees currently residing in Türkiye as one of his primary goals, especially in view of the upcoming elections in 2028, as the subject remains an important preoccupation among the population. Hence, the fall of Assad gives Türkiye an opportunity to stabilize Syria and create the necessary conditions for these refugees to feel safe and hopeful enough about the future economic conditions in Syria to return home. Moreover, it is clear that many Syrians have already started to return home, while others are seriously considering doing the same, proving the Turkish president a little more right.

Finally, Türkiye may find it easier to establish security zones along its border and strengthen its control over northern Syria with an allied regime being in place in Damascus for the first time since the fall of the Ottoman Empire. These zones are expected to provide greater protection against insurgent groups and Kurdish fighters. Hence, the securitization of its southern border, rid of the presence of a hostile regime in Damascus, can be seen as one of the greatest achievements of this regime change for Türkiye, further contributing to its national security—something that the president can claim as a political benefit for Erdogan.

The Syrian Bill

However, the picture is not entirely rosy either, and the fall of the Baathist regime in Damascus could lead to further destabilization of the country after a few years of relative calm, thus negatively impacting Türkiye. In general, it would be wiser for Erdogan to also expect a downside behind this apparent victory. So, first, let us talk numbers—not the kind politicians throw around in press briefings, but the kind that quietly bleed through national budgets and haunt long-term strategy. Syria’s reconstruction is not going to come cheap. And guess who is footing part of the bill? Türkiye. Türkiye is not just a neighbor peering over the fence; it is hosting millions of Syrian refugees, and like it or not, that places it squarely in the reconstruction hot seat.

Ankara has already signaled a willingness to help rebuild its war-ravaged neighbor—cue Erdogan’s latest diplomatic overtures—but this is more than a goodwill gesture. It is a high-stakes balancing act. Supporting infrastructure, managing the logistics of refugee return, and fostering sustainable development in the volatile northern regions? That is not a weekend project—it is a generational one. And make no mistake, it will test both Türkiye’s wallet and its political stamina. Rebuilding Syria may also mean rebuilding trust. Or, more likely, bracing for a cold diplomatic standoff. Türkiye has played a long game in Syria, backing opposition forces and carving out influence zones, especially in Idlib. But the political terrain is shifting fast. HTS’s growing prominence, coupled with the emergence of a potentially less Türkiye-friendly government in Damascus, could spell trouble. A Syria that is more autonomous—and less receptive to Ankara’s military footprint or its alliances with rebel groups—could ignite diplomatic tensions that are anything but theoretical.

Let us not forget: Türkiye is not the only power eyeing a post-Assad Syria. The U.S. is still firmly in play, backing Kurdish forces in the north—forces Ankara sees as a threat wrapped in a flag. And the Gulf monarchies? They may have their own plans, their own checkbooks, and perhaps their own preferred partners in Damascus. If Riyadh or Doha start cozying up to the new Syrian leadership, Türkiye’s regional strategy could quickly feel more like a solo than a symphony. So, Türkiye may dream of a secure southern border, a weakened Kurdish push for autonomy, and a streamlined refugee return. But dreams come with invoices. Between the steep costs of reconstruction, rising friction with Damascus, and geopolitical elbowing from the U.S. and Gulf players, Ankara’s post-Assad playbook is anything but straightforward. This is not just a question of whether Türkiye can win influence in Syria, but whether it can afford the price tag.

Ankara’s Fragile Leverage

Now that the dust is settling in Damascus and HTS’s black-and-white banners have been hastily swapped for tailored suits and diplomatic jargon, Ankara is finding itself in an increasingly ambiguous dance with Syria’s new leadership. On paper, Erdogan should be basking in vindication—after all, Türkiye’s long bet on the opposition has paid off. However, beneath the surface, the situation is far more complex. While Türkiye has undoubtedly been instrumental in shaping the post-Assad order, notably by supporting the rebel coalition that led the charge to Damascus, it does not fully control the monster it helped create.

HTS and its leader, Ahmad al-Sharaa (who now presides over Syria’s transition government), were once officially branded a terrorist group by Ankara itself. Now, a fragile, pragmatic cooperation binds the two: a relationship defined more by tactical alignment than ideological harmony. Still, Türkiye has not given up its ambitions to mold the new Syria. Turkish officials, including Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan, have wasted no time swooping into Damascus with grand offers: military training, reconstruction funds, and even help building a new national army.

These overtures, however, come with clear strings attached—namely, the expectation that the new regime clamps down on Kurdish autonomy and keeps Ankara’s interests front and center. Idlib remains a sticking point. Türkiye’s military footprint there is not only symbolic but strategic. The area has long served as a buffer zone against Kurdish forces and Assad loyalists alike. But as the new Syrian leadership consolidates power, questions arise: Will Ankara’s presence be tolerated as a necessary security umbrella or resented as foreign meddling? As El País reported, Türkiye’s sprawling network of intelligence, police, and media in Syria’s capital may feel more like occupation than cooperation to some within HTS’s orbit.

And therein lies the rub: HTS is not the Syrian National Army. It is not built to be Türkiye’s puppet. As Chatham House cautions, Ankara’s newfound leverage comes with equally weighty responsibilities and potential blowback. HTS may grow increasingly assertive, its leaders emboldened by popular support and their newfound legitimacy. If the governance style in Damascus begins to diverge too far from Ankara’s preferences—such as veering too Islamist or too independent—friction is inevitable. So, is Türkiye the new kingmaker in Syria? Perhaps. But if Erdogan hoped for a pliable ally in Damascus, he may find himself instead navigating a precarious alliance with a regime that owes him gratitude, but not obedience. And in Middle Eastern politics, that distinction makes all the difference.

Erdoğan’s Grand Narrative

For Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the fall of Assad is more than a geopolitical trophy; it is a golden political script, handed to him just in time for the next domestic chapter. In classic Erdogan fashion, the narrative is already being spun: Türkiye stood firm, played the long game, and emerged with moral authority and regional leverage. And now? Now comes the payback at home. As Dareen Khalifa from The Guardian notes, Ankara is walking a “victory lap,” with Turkish officials promptly planting their flag over the reopened embassy in Damascus just days after Assad’s departure. This is why the Turkish intelligence chief, Ibrahim Kalin’s high-profile visit can be seen as the first signal that Erdogan intends to capitalize on the moment to its fullest extent.

This is no small matter. With over 3.2 million Syrian refugees inside Turkish borders, Erdogan is threading the needle between his image as a protector of the ummah and his nationalist allies’ less charitable view of displaced Syrians. Now, with Syria inching toward stability, Erdogan can claim the moral high ground while quietly facilitating returns. His strategy is plain and simple: turning a political liability into a triumph. In this context, Assad’s downfall gives Erdogan the opportunity to “bolster his brand” as the leader who both sheltered Syrians and orchestrated their dignified return. Such an outcome would likely soothe domestic tensions while polishing his legacy.

And indeed, public opinion is watching closely. As Chatham House points out, Turks remain divided. While some may be wary of repatriation promises, others demand quicker returns amid economic woes. Erdogan understands this balancing act all too well. He is relying on the optics of diplomacy in Damascus and reconstruction in Syria to calm internal dissent, rally nationalist pride, and reinforce his message to voters. From his perspective, the strategy has succeeded against the odds: he played the regional game and won. But with every political win comes expectation. Now, he must deliver.

At the Table—or on It?

Now that Assad is finally out of the picture, the international stage surrounding Syria is being re-scripted. In this new context, Türkiye is not just rewriting its role but vying for top billing. While other regional powers scramble to recalibrate, Ankara has made its position unmistakably clear: this post-Assad Syria will be navigated on Turkish terms—or at least under heavy Turkish influence. As prophesied by Erdogan, his allies would one day pray in the courtyards of the Umayyad Mosque after Assad’s fall, and this vision now appears to be edging toward reality.

Kalin was recently spotted strolling through the streets of Damascus like a man surveying new real estate. Not particularly subtle, but certainly strategic. Türkiye’s clout in Syria is no accident; it is the result of a long game—a mixture of ideological ambition, hard power, and cold pragmatism. With HTS consolidating control and forming a provisional government, Türkiye is not only the dominant external actor in Syria but can arguably be seen as the broker of what comes next. Through a careful dance of cooperation and containment, Ankara has turned HTS from a terrorist-designated entity into a de facto gatekeeper: helping curb drug trafficking, controlling ISIS infiltration, and detaining those Ankara wants removed.

In this new chapter, the central question is how Türkiye will maneuver its relationships with the real titans of geopolitics, such as the U.S., Russia, and Iran. Moscow and Tehran come first. Their influence was tethered to Assad’s survival. With him gone, Ankara has seized the momentum. Russia, preoccupied and overstretched, is unlikely to reassert itself decisively in northern Syria. Iran, whose support for Damascus had always been more ideological than strategic, now finds itself sidelined—especially in Sunni-majority areas where Turkish-backed groups hold sway. And the United States? That relationship remains far more complicated.

Despite being NATO allies, Ankara and Washington remain deeply divided on the Kurdish question. The U.S. continues to support the SDF, whose backbone, the YPG, is anathema to Türkiye. Erdogan’s policy is unambiguous: dismantle any form of Kurdish autonomy near the southern border, with or without U.S. approval. With a planned U.S. withdrawal from Syria by 2026, Ankara senses opportunity. The departure of American forces may translate into increased Turkish influence—not just physically, but diplomatically, economically, and ideologically. In short, Syria’s power vacuum has become Türkiye’s geopolitical feast, and Erdogan is already carving out his preferred portions. Whether other global actors will find themselves at the table—or on the menu—remains to be seen.

Not the Endgame Yet

So, has Recep Tayyip Erdogan truly won in Syria? That depends on how “victory” is defined—and whose scoreboard is being used. If success is measured purely in geopolitical terms, Türkiye has clearly advanced several key positions on the chessboard: Assad is out, HTS is in (with Ankara’s tacit approval), and Turkish officials are already shaking hands in Damascus while planning border security zones. Not bad for a player once accused of overreach. However, if Erdogan was hoping for a pliable, pro-Türkiye government that would resolve the refugee crisis, eliminate Kurdish threats, and grant Ankara veto power over Syria’s future, it may be premature to declare “mission accomplished.”

Fundamentally, Türkiye has made substantial progress on some of its long-standing objectives in Syria. According to the Alma Research and Education Center, Ankara’s strategy has consistently revolved

around three pillars: suppressing Kurdish autonomy in northern Syria, enabling the return of millions of Syrian refugees, and shaping a Sunni-friendly post-Assad state. With HTS now seated in Damascus and the YPG’s position weakened, two of these ambitions have taken tangible form. The Turkish military’s persistent operations against the SDF and the symbolic display of Turkish flags across rebel-held zones have given Erdogan the aura of a kingmaker in Syria’s emerging order. Still, Türkiye’s influence, while significant, is far from absolute.

As Chatham House aptly noted, Erdogan’s victory is “vindicated but not guaranteed,” and his government now faces a delicate balancing act between exerting power and managing new responsibilities. One major concern is whether HTS, emboldened by its lightning-fast offensive and growing popular legitimacy among segments of the Syrian population, will continue to heed Ankara’s guidance. The group’s leader, Ahmad al-Sharaa (also known as Abu Mohammad al-Julani), may owe tactical gratitude to Türkiye, but he does not take orders from it. As CEPA observes, “it is doubtful that Turkey was ever the HTS puppet-master in the first place,” and the militia may now drift further from Ankara’s orbit—particularly if Western powers begin to engage with it for the sake of regional stability. More critically, Türkiye may now be facing a paradox of its own making. While Erdogan’s inner circle celebrates a rare foreign policy achievement, his public posture has remained notably restrained.

Why the caution? Possibly because post-Assad Syria resembles less a strategic playground and more a political minefield. HTS’s Islamist foundations make it an uncomfortable partner for long-term cooperation—especially from the perspective of Türkiye’s Western allies. Moreover, Erdogan’s vision of an “AKP-style government in Damascus,” as described by CEPA, remains aspirational at best. Although the new leadership may share some ideological proximity with the Justice and Development Party, it does not imply a willingness to accept Turkish oversight. Then there is the refugee question. Turkish officials have already begun testing the waters for voluntary returns, and local media have reported a modest but growing flow of Syrians crossing back over the border. This is a development Erdogan is certain to highlight in the run-up to the 2028 elections.

Yet Chatham House tempers this optimism, noting that “conditions are still dire” in many parts of Syria, making mass returns improbable in the near future. A few thousand celebratory homecomings in Hatay province do not equate to the repatriation of 3.6 million people. Furthermore, the economic elephant in the room remains: reconstruction. Ankara may have re-entered Damascus in a black sedan, but it will not be long before it is expected to bring bulldozers and checkbooks. As HTS attempts to govern a fractured state, Türkiye will inevitably face pressure to support infrastructure, service delivery, and security—all while managing the perception risk of being seen not as a partner, but as an occupier. The Guardian notes that Türkiye’s initial reluctance to back the HTS offensive was driven in part by fears of precisely this outcome: a “catastrophic success” leaving Ankara responsible for a volatile post-war landscape.

Strategically, Erdogan has reasserted Türkiye’s influence in a region where Russia and Iran once held dominance. The Council on Foreign Relations accurately describes the current period as a “risky new chapter,” in which Ankara may find itself overstretched militarily, diplomatically, and financially. The international stage is closely observing: the U.S. remains entangled in the Kurdish question, Gulf states are eyeing Damascus for their own leverage, and European powers are recalibrating how best to engage through the lens of refugee returns. Within this tangled web, Erdogan may be the loudest voice—but he is far from the only one. In the end, Türkiye’s Syria campaign may be remembered not as a final checkmate, but as a high-stakes middle game. Erdogan has positioned.

Türkiye’s Syria campaign may be remembered not as a final checkmate, but as a high-stakes middle game.

Fundamentally, Türkiye has made substantial progress on some of its long-standing objectives in Syria. According to the Alma Research and Education Center, Ankara’s strategy has consistently revolved around three pillars: suppressing Kurdish autonomy in northern Syria, enabling the return of millions of Syrian refugees, and shaping a Sunni-friendly post-Assad state. With HTS now seated in Damascus and the YPG’s position weakened, two of these ambitions have taken tangible form. The Turkish military’s persistent operations against the SDF and the symbolic display of Turkish flags across rebel-held zones have given Erdogan the aura of a kingmaker in Syria’s emerging order. Still, Türkiye’s influence, while significant, is far from absolute.

As Chatham House aptly noted, Erdogan’s victory is “vindicated but not guaranteed,” and his government now faces a delicate balancing act between exerting power and managing new responsibilities. One major concern is whether HTS, emboldened by its lightning-fast offensive and growing popular legitimacy among segments of the Syrian population, will continue to heed Ankara’s guidance. The group’s leader, Ahmad al-Sharaa (also known as Abu Mohammad al-Julani), may owe tactical gratitude to Türkiye, but he does not take orders from it. As CEPA observes, “it is doubtful that Turkey was ever the HTS puppet-master in the first place,” and the militia may now drift further from Ankara’s orbit—particularly if Western powers begin to engage with it for the sake of regional stability. More critically, Türkiye may now be facing a paradox of its own making. While Erdogan’s inner circle celebrates a rare foreign policy achievement, his public posture has remained notably restrained.

Why the caution? Possibly because post-Assad Syria resembles less a strategic playground and more a political minefield. HTS’s Islamist foundations make it an uncomfortable partner for long-term cooperation—especially from the perspective of Türkiye’s Western allies. Moreover, Erdogan’s vision of an “AKP-style government in Damascus,” as described by CEPA, remains aspirational at best. Although the new leadership may share some ideological proximity with the Justice and Development Party, it does not imply a willingness to accept Turkish oversight. Then there is the refugee question. Turkish officials have already begun testing the waters for voluntary returns, and local media have reported a modest but growing flow of Syrians crossing back over the border. This is a development Erdogan is certain to highlight in the run-up to the 2028 elections.

Yet Chatham House tempers this optimism, noting that “conditions are still dire” in many parts of Syria, making mass returns improbable in the near future. A few thousand celebratory homecomings in Hatay province do not equate to the repatriation of 3.6 million people. Furthermore, the economic elephant in the room remains: reconstruction. Ankara may have re-entered Damascus in a black sedan, but it will not be long before it is expected to bring bulldozers and checkbooks. As HTS attempts to govern a fractured state, Türkiye will inevitably face pressure to support infrastructure, service delivery, and security—all while managing the perception risk of being seen not as a partner, but as an occupier. The Guardian notes that Türkiye’s initial reluctance to back the HTS offensive was driven in part by fears of precisely this outcome: a “catastrophic success” leaving Ankara responsible for a volatile post-war landscape.

Strategically, Erdogan has reasserted Türkiye’s influence in a region where Russia and Iran once held dominance. The Council on Foreign Relations accurately describes the current period as a “risky new chapter,” in which Ankara may find itself overstretched militarily, diplomatically, and financially. The international stage is closely observing: the U.S. remains entangled in the Kurdish question, Gulf states are eyeing Damascus for their own leverage, and European powers are recalibrating how best to engage through the lens of refugee returns. Within this tangled web, Erdogan may be the loudest voice—but he is far from the only one. In the end, Türkiye’s Syria campaign may be remembered not as a final checkmate, but as a high-stakes middle game. Erdogan has positioned.

Recommended

Soft Power, Hard Tactics, and U.S. Resistance

Is a Common European Identity Still Possible?

India’s Internal Challenges to Global Leadership

The Empire That Fights to Exist

How Jeffersonians See Foreign Burdens?