The text underlines how Russia, the European Union, and the United States lack a coherent long-term strategy in Central Asia, potentially leading to increased Chinese and Russian influence and missed economic opportunities in the region.

Written By; Eldaniz Gusseinov – Sep17, 2023

Prior to the inaugural summit in the “Central Asia + US” format, discussions have intensified regarding the necessity for the US to amplify its foothold in Central Asia. While prevalent narratives suggest Russia’s diminishing influence in the region, with China poised to take its place, Kazakhstan stands as a counterexample. Contrary to popular belief, Russia’s influence in Kazakhstan remains robust. Historically, both the U.S. and the European Union have enjoyed a more pronounced influence in Kazakhstan compared to Russia and China. However, this influence seems to be waning. A critical concern underlying this dynamic is the apparent absence of a cohesive long-term strategy by the U.S. and the European Union in Central Asia. Often, their engagement appears reactionary, moving from one crisis to the next.

Is Russia really losing influence in Central Asia?

The diminishing influence of Russia in Central Asia is frequently exemplified by Kazakhstan’s stance, notably its non-recognition of the so-called LNR and DNR, coupled with its adherence to anti-Russian sanctions. Yet, this perspective offers only a partial view of Russia’s waning prominence in Kazakhstan. Delving into the economic aspects of international engagements with Kazakhstan, many assert the European Union stands as its principal trading ally. The ongoing conflict in Ukraine has spurred Russia to bolster its economic ties with Central Asian nations. By 2022, Russia emerged as Kazakhstan’s preeminent exporter. In contrast, China holds a comparatively subdued role in Kazakhstan’s export landscape. Analyzing the 2022 data against the prior year reveals a growth in both imports and exports for all major stakeholders, with Russia as the sole exception. A nearly 3% contraction in Russia’s trade share, primarily stemming from reduced imports, suggests a subtle decline in absolute monetary terms. This trend underscores the significance of Kazakhstan as a conduit for parallel imports destined for Russia.

During the initial eight months of 2022, a surge in exports from the European Union to Kazakhstan was observed, with pharmaceuticals seeing a 25.6% uptick, tractors by 90.5%, automobiles close to 100%, and computer equipment approximately 50%. Simultaneously, nearly 90% of Kazakhstan’s exports to the EU in 2022 comprised petroleum products and oil. Intriguingly, the monetary value of these exports mirrored the 2021 figures, hinting at a reduction in Kazakhstan’s actual export volumes to the EU compared to the previous year. This shift in trade dynamics is likely attributed to escalating energy prices. In the same year, Kazakhstan dispatched 65.2 million tonnes of oil and gas condensate, valued at US$46.9 billion — a slight volume decrease of 0.7 percentage points, yet a notable 51% surge in value compared to 2021. Concurrently, Kazakhstan augmented its energy consignments to both China and Türkiye..

The influence of the US and EU in Kazakhstan was higher than that of Russia and China

To gauge the influence, or more aptly, the “capacity to influence” one external actor over another, one can utilize the Foreign Bilateral Capacity Influence metric. This data is derived from the Formal Bilateral Influence Capacity produced by both the Atlantic Council and the Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures at the University of Denver’s Josef Korbel School of International Studies. Hence, every reference to “influence” in this context should be interpreted as “influence capacity.”

The calculation of the influence capacity of one country on another is based on sub- indicators such as 1) trade in goods, 2) foreign aid, 3) arms trade, 4) diplomatic exchanges (i.e., the presence of embassies), 5) joint membership in intergovernmental organizations, 6) trade agreements, and 7) military alliances. The FBIC index also uses country-level data on 8) GDP and 9) military expenditures as denominators for dependence indicators. All these indices are proportionally related, ranging between values of 0 (minimum) and 1 (maximum). The relative weightage of each indicator was established through expert consultations.

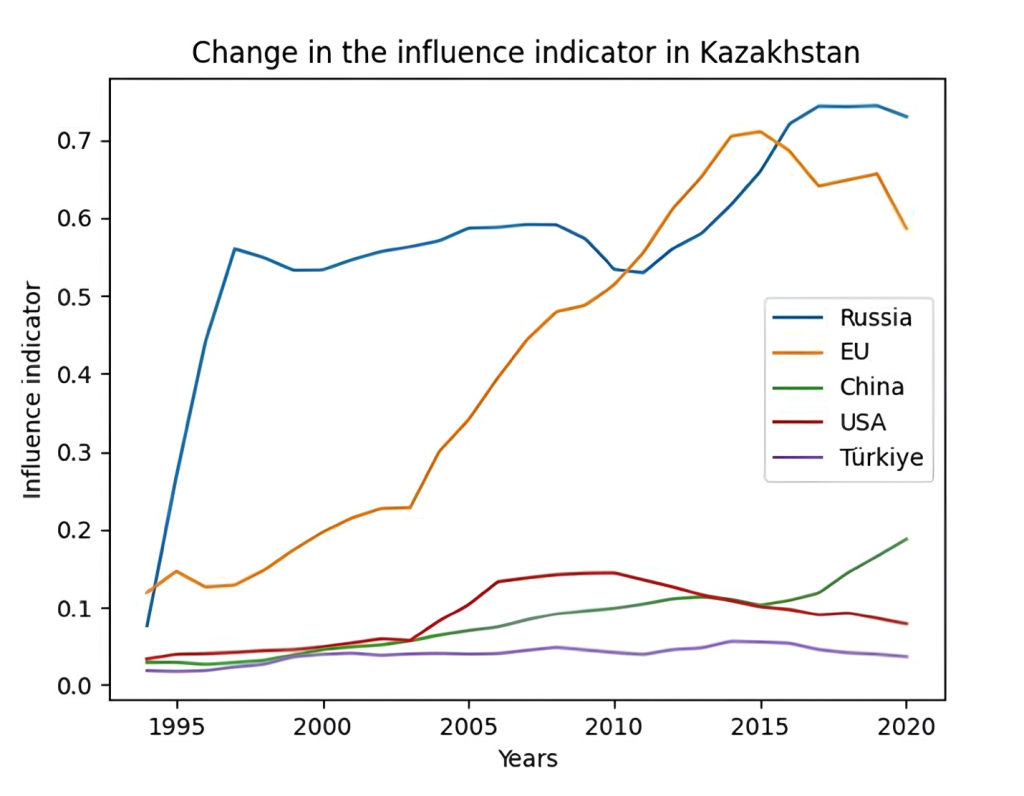

It’s feasible to gather all this data, adjust for changes in EU membership, and then visually represent the findings on a graph. This graphical representation reveals a growing potential of Russian influence on Kazakhstan from 1994 (0.07) to 2020 (0.73), indicating Russia’s dominant position among the studied nations. Interestingly, Russia’s influence dipped until 2010 before surpassing the European Union. The EU’s influence started dwindling since 2015, likely attributable to a decline in humanitarian aid and Kazakhstan’s heightened collaboration with Russia within frameworks like the EAEU and CSTO.

In 2020, the European Union followed Russia with an influence score of 0.64, up from 0.12 in 1994. The United States, while impactful, was less so than Russia or the EU, showing a growth from 0.03 in 1994 to 0.08 in 2020. Both Türkiye and China had minimal influence on Kazakhstan, but China’s footprint has grown recently, climbing from 0.03 in 1994 to 0.19 in 2020. Türkiye’s influence, however, remained under 0.06 throughout.

These statistics defy the conventional belief of China’s rising dominance in Central Asia. A closer look reveals a decline in the EU’s influence since 2016, countered by a surge in Russian influence. Concurrently, China’s influence spiked by 71% from 2016 to 2020, a unique trend compared to other actors. Türkiye’s influence remained consistent, whereas the U.S. influence dropped by 19.6% during the same period.

In summary, between 2016 and 2020, Kazakhstan appears most influenced by Russia and the EU, with China on the rise. Despite this, an economic examination from 2016 to 2020 highlights the EU’s dominance in the Kazakh economic sector, holding around 73% influence. In comparison, nations like Russia, China, and Türkiye don’t surpass 15% individually. This dominance suggests that Russia’s predominant influence in Kazakhstan primarily stems from alliances like the CSTO and the EAEU.

Picture 1. Change in the FBIC-Index in Kazakhstan from 1994 to 2020 based on data from the Atlantic Council and Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures at the University of Denver’s Josef Korbel School of International Studies

Fluctuation of European and US interests in Central Asia

When discussions arise about the potential expansion of U.S. influence inCentral Asia, two pivotal questions surface: 1. What resources is the U.S. willing to allocate to augment its presence in Central Asia? 2. Do the U.S. and its EU allies possess a coherent long-term strategy for the region?

Addressing the first query, there’s an apparent reticence from the U.S. to heavily invest its resources for regional influence. The scheduled meeting with President Biden appears to be a belated gesture, especially when considering the active diplomacy of various European nations in Central Asia. Before U.S. Secretary of State Blinken’s visit, a slew of European dignitaries, ranging from Luxembourg to Finland, had already engaged with Central Asian nations. It’s also noteworthy that Blinken, during his tour, limited his visits to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Furthermore, during Kazakh President Tokayev’s U.S. visit in September 2022, he convened with numerous international leaders like UN Secretary-General António Guterres, European Council President Charles Michel, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, and Austrian President Alexander Van der Bellen. Notably absent from this list was a meeting with President Joe Biden.

This leads to the interpretation that, given the inaugural nature of the Central Asia-US summit, the U.S. lacks a definitive long-term vision for the region. The EU’s approach appears equally sporadic and lacks consistency, unlike the structured engagements of China and Russia. Oddly, the focus of these western powers seems erratic, often shifting abruptly during crises. After the 2014 Ukraine crisis, the Foreign Affairs Council of the European Union, in 2016, vowed to intensify its engagements with Central Asian nations. Yet, European diplomats have since lamented their inattention to the region. This sentiment prevails even after the EU rolled out a fresh Central Asia strategy in 2019, succeeding its last one from 2007. In a similar vein, the U.S. unveiled its mid-term strategy for Central Asia, spanning 2019-2025.

Potential Consequences of Crisis-to-Crisis Engagement in Central Asia

Central Asia, with its deep historical roots and complex geopolitical landscape, is increasingly capturing global attention. Yet, the engagement of major powers like the United States and the European Union appears sporadic, often spurred by crises rather than strategic foresight. Such inconsistent involvement might have profound implications, reshaping the regional power dynamics and beyond.

This intermittent focus by the US and the EU paves the way for other nations, notably China and Russia, to consolidate their influence. This creates a strategic void, often filled by the most opportunistic player, which may compromise the autonomy and self-determination of Central Asian countries. This piecemeal strategy can inadvertently make these nations disproportionately reliant on a select few dominant powers.

Furthermore, this “crisis-to-crisis”mode of engagement erodes the soft power of the US and the EU in Central Asia. Over time, Central Asian countries might drift away from Western democratic ideals, legal frameworks, and norms, gravitating towards the models presented by more steadfast allies. Security-wise, the evolving threats—ranging from extremist ideologies to territorial conflicts—necessitate a consistent diplomatic presence to grasp the nuanced regional dynamics. A sporadic engagement lacks this depth, impeding timely interventions or preemptive actions against threats.

Economically, Central Asia, blessed with abundant natural resources and a pivotal geographic position, holds immense potential. An inconsistent strategy misses out on lucrative trade, investment, and collaborative opportunities. Moreover, policies driven by immediate crises often lack a coherent, long-term vision, making the international stance unpredictable. Such unpredictability can undermine trust-building with Central Asian nations, inadvertently empowering rival powers or undermining global institutions. For instance, the U.S’s Medium-Term Strategy 2019-2025 articulates its commitment to Central Asian countries’ sovereignty through economic prosperity. Yet, during a consultative meeting of Central Asian leaders on September 14-15, it became evident from the discussions and agreements that prioritizing transportation and logistics is vital for the region’s ambition to emerge as a significant logistics hub. This aspect is conspicuously absent in the US strategy. For sustainable economic growth, Central Asia seeks crucial investments in transport and logistics, such as port modernization, road enhancements, and harmonizing customs systems. It’s highly probable that regional leaders will spotlight this topic at the imminent summit.

Eldaniz Gusseinov a specialist in European and International Studies at the HEARTLAND Expert Analytical Center based in Almaty