Biden’s America’s foreign policy has evolved from Trump’s unilateralism to multilateralism. Revitalizing the transatlantic world is important, but the United States still faces challenges.

“We stand, in my view, at an inflection point in history. Instead of continuing to fight the wars of the past, we are fixing our eyes on devoting our resources to the challenges that hold the keys to our collective future: ending this pandemic; addressing the climate crisis; managing the shifts in global power dynamics; shaping the rules of the world on vital issues like trade, cyber, and emerging technologies; and facing the threat of terrorism as it stands today.” This excerpt is from President Joe Biden’s first speech to the United Nations General Assembly in September 2021, emphasizing his administration’s intention to shift away from the unilateral and nationalist “America First” foreign policy observed during the presidency of Donald Trump into a foreign policy guided by multilateralism to address pressing global challenges. Indeed, surveys such as those conducted by the Pew Research Centre between 2017-2020 consistently found that confidence in American leadership in international issues during the Trump era had been significantly dented compared to the years of the Obama presidency.

Consequently, returning America’s foreign policy to a state of ‘normalcy’ by rescinding policies percieved as erratic under Trump, recommitting Washington’s obligations to allies and international institutions, and restoring the country’s standing and credibility as a reliable leader and partner at the global stage, constituted Biden’s most immediate foreign policy priorities. However, with approximately one year left before the next presidential elections in 2024, has the Biden administration’s foreign policy succeeded in reinstating America to a leadership position in international affairs?

The earliest demonstration of Biden’s departure from his predecessor’s policies was his immediate executive action that paved the way for the United States to rejoin the Paris Climate Agreement on his first day in office. His decision to appoint John Kerry, a veteran diplomat as a special presidential envoy for climate, was equally of great impetus for observers seeking to situate the vitality of climate change in Biden’s foreign policy agenda. Top of FormHenceforth, Biden has backed America’s commitment to international climate change action by among other things, organizing a Leaders Summit on Climate in 2021 that brought 40 leaders to rally around the climate crisis, and taking leading roles in the subsequent meetings of Conference of Parties (COP). In COP26 and COP27, the United States was integral to the completion of Paris Agreement Rulebook, establishment of the Loss and Damage Fund, and co-leading the Forest and Climate Leaders’ Partnership. These initiatives are integral to mitigating the climate crisis by mobilizing stronger climate action from government, philanthropic, and multilateral finance institutions.Top of Form

However, in as much as Biden administration’s approach to climate action may be characterized as cooperative, the inclusion of interstate strategic competition into the US national security strategy policy documents has meant that competing for opportunities arising from climate change has been an important aspect of US foreign policy.Top of Form Specifically, the competitive aspects of Biden’s climate action policies is indicative of the strategic response to China’s expanding support for its domestic clean-energy industries and foreign energy projects. Thus, the passage of the ambitious Inflation Reduction Act, which contains provisions worth USD 369 billion in climate change mitigation through investment in energy innovation and green manufacturing, should be seen as partial, yet strategic response, to counter China’s contemporary dominance. Indeed, Secretary of State Blinken reiterated this competitiveness when he acknowledged that the United States will not be in a position to win the long-term strategic competition with China if they cannot lead the renewable energy revolution.

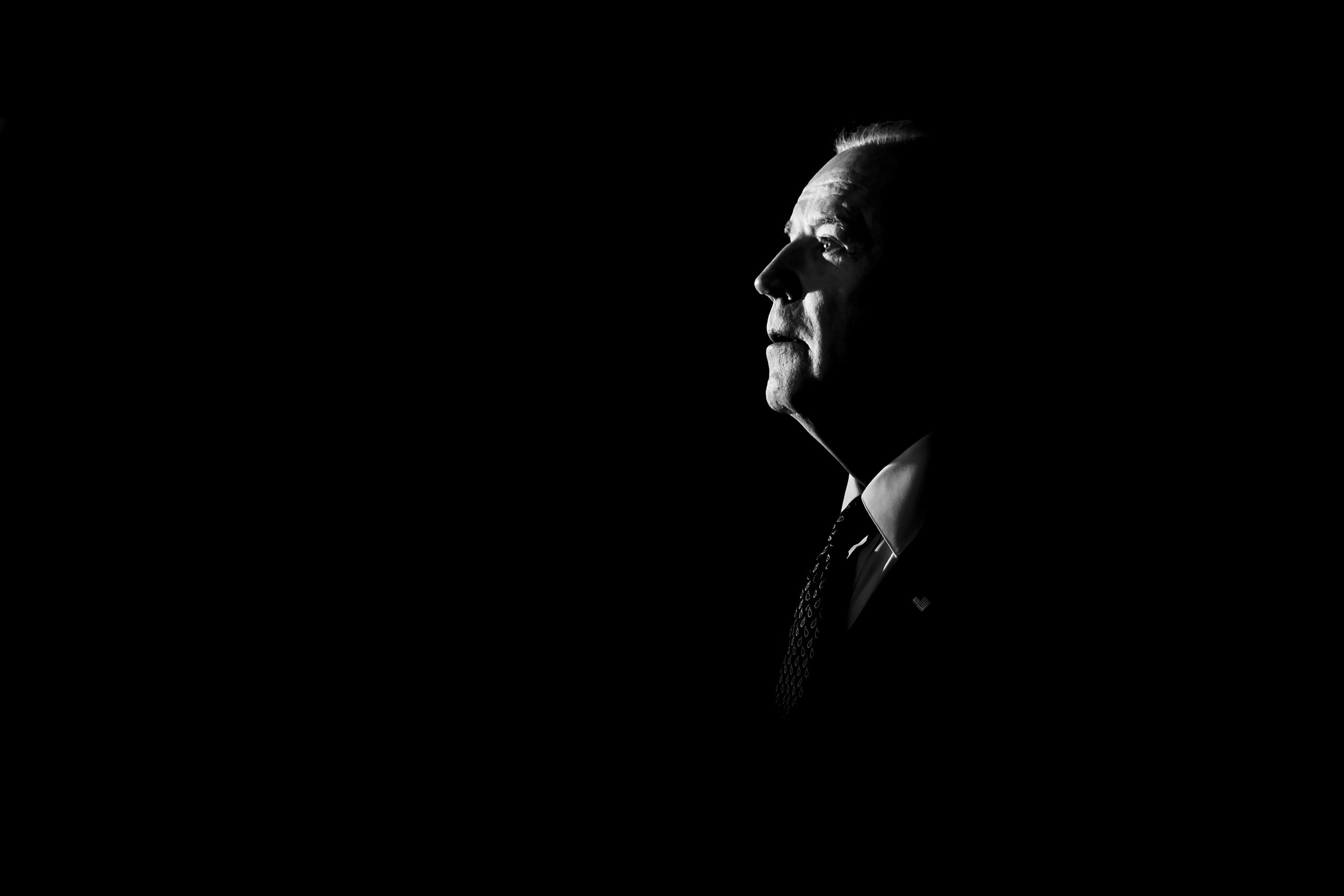

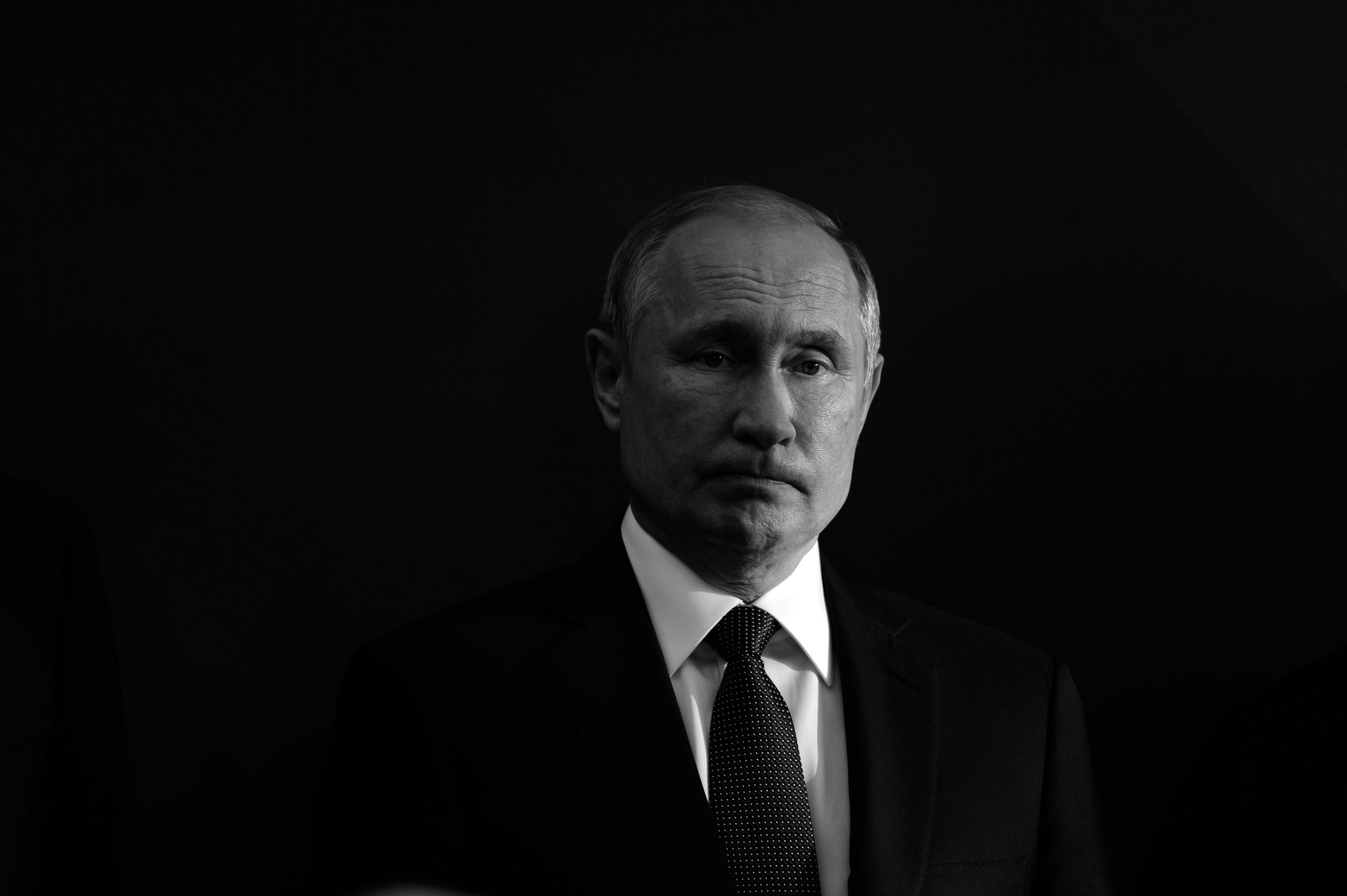

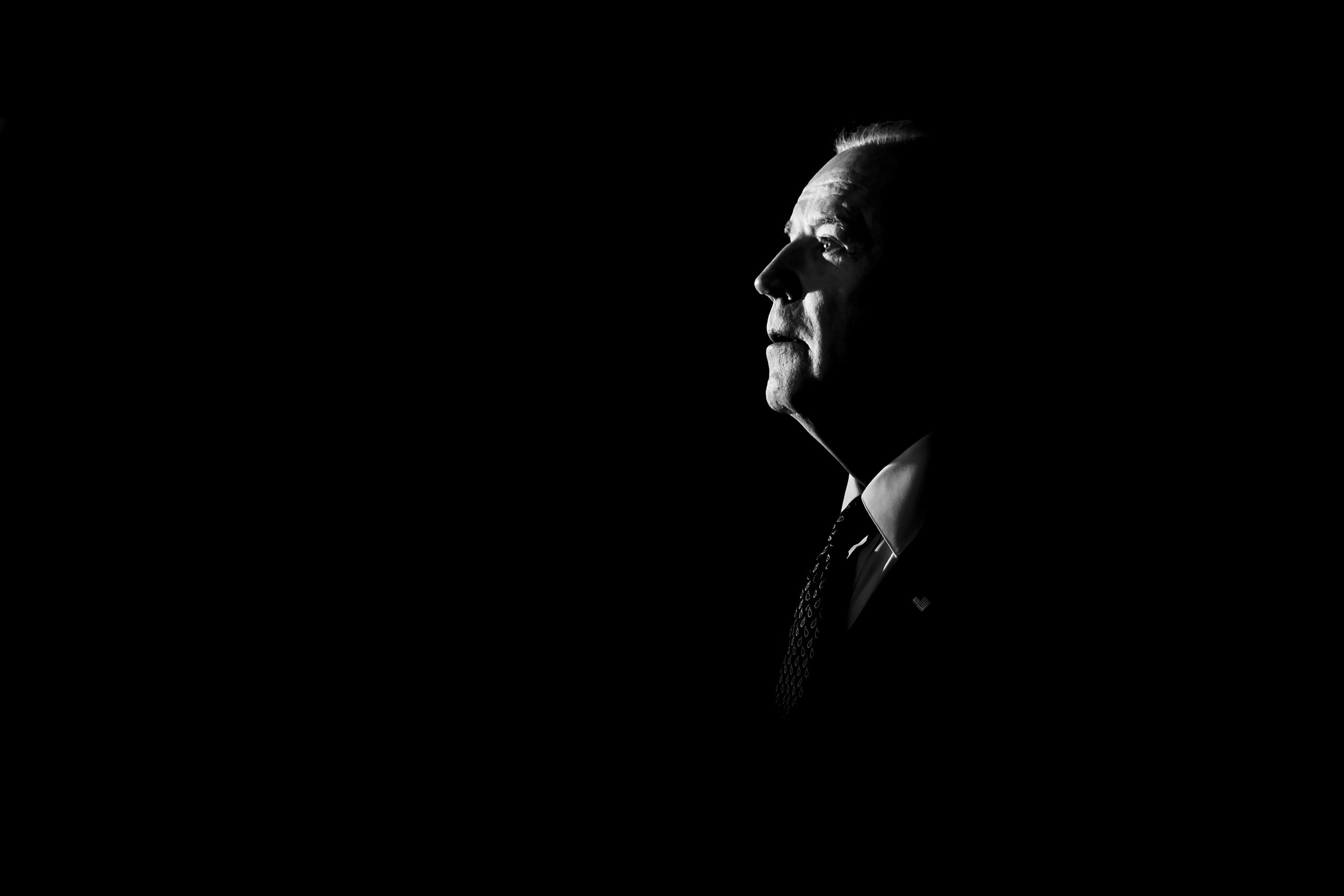

Although climate change has been an important entry point for the US attempt to reassert its leadership in global governance, Top of Form there has not been a bigger issue that invoked anticipation of Biden’s foreign policy than the question of revamping US-NATO relations. For the four years that Trump was in power, his rhetoric and actions put substantial constraints on the US-NATO relations. Trump not only criticized NATO countries for their limited military spending and threatened to end US membership in the alliance, but he also emphasized that continuous reliance on US military intervention or deterrence in conflicts by allies would no longer be sustainable—a policy he pursued, albeit unsuccessfully, through his plan to withdraw 12,000 US troops from Germany. Equally alarming was Trump’s dalliance with Putin who for the entirety of his leadership, has been perceived by NATO allies as not only having questionable democratic credentials but was also accused of meddling in the 2016 elections in the US. Mending the broken rifts in this relationship was therefore vital, and Biden’s foreign policy in contrast to Trump, has generously embraced the principles of multilateralism, emphasizing the essence of strengthening international coalitions. Indeed, nowhere has this been evident than in the Ukraine-Russia war and US support for Finland and Sweden’s membership to NATO.

In Ukraine, the Biden administration has been fundamental in urging the Alliance to increase and sustain its support, both in quantity and capability to Kyiv. Furthermore, since the Russian invasion, the Biden administration has overseen the historic transfer of more than USD 71 billion in humanitarian, military, and financial assistance to Ukraine, according to Kiel Institute for the World Economy, making Ukraine the highest recipient of US aid. On the enlargement of NATO membership, Biden supported the candidacy of Finland and Sweden, and played a vital role in urging Turkey to sign the ascension agreement for Finland and drop its protracted objection to the membership of Sweden. While re-energizing NATO has been a key achievement, the establishment of the ambitious defense industrial partnership between Australia, United Kingdom, and United States (AUKUS), marked another key milestone for Washington’s long-term goals of shoring regional power balance as a deterrence against China in the Indo-Pacific region. In all aspects, Biden administration has been successful on the multilateral foreign policy front.

However, whereas Biden broke ranks with his predecessor on certain foreign policy issues, there has been some resemblance of continuity and to a greater extent, failure, particularly with regard to the global war on terror. Two years after his election, Biden acted on Trump’s commitment to end “America’s everlasting wars.” It is important to appreciate that Biden had little room to maneuver in Afghanistan because of the poorly negotiated Doha Agreement with Taliban which stipulated a specific time for complete withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan and little in holding Taliban into account apart from the promise of counterterrorism. As such, what is seen as Biden’s foreign policy failure in Afghanistan should be considered as having more to do with the chaotic and catastrophic manner in which the withdrawal was undertaken, rather than the whole idea of withdrawing from Afghanistan. Nonetheless, on a broader context of the global war on terror the threat of terrorism has expanded even further in regions such as Africa, yet under Biden, counterterrorism efforts have been reduced to few airstrikes, most of which are conducted on the basis of “self-defense.”

Yet, the biggest challenge to Biden’s foreign policy, in the form of the war in Gaza may yet become full-blown. Whereas Biden responded firmly by channeling aid and making a trip to Israel, his administration’s foreign policy has increasingly come under scrutiny with pressure amounting from both abroad and at home for more accountability on the part of the Israelis in their counterterrorism war on Hamas. Still, the war has the potential to embroil th broader Middle East region into the conflict, with US-Iran relations, the most likely to have far-reaching repercussions. Indeed, Iran has been accused of providing support to Hamas whose grotesque attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, has led to its designation as a terrorist organization by the United States, European Union, Israel, Canada, United Kingdom, and Australia. For Biden, taking a hard stance against Iran would mean scuttling any hopes for the revival of the Iran nuclear deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, that was conceived during the Obama and scuttled by the Trump administration.

All things considered, the Biden administration has done well to restore America’s active role in international issues and created a resemblance of order in a system that was rapidly decaying during the Trump administration. Yet, it cannot be emphasized any further, that the increased participation of the United States in international affairs need to be orchestrated in a cautious yet sufficient manner that fosters wider global cooperation in dealing with pressing global challenges. Over the last two decades since the turn of the third millennium, the structure of the international system has undergone significant changes that necessitate effective leadership of major powers without them having to become overly dominant. So far, Biden has shown effective statesmanship in crafting a foreign policy that has ensured for example, Ukraine has had access to support in its war with Russia, and at the same time, mitigating the chances of a direct conflict between the US and Russia, which in all measures, could be catastrophic for humanity. Thus, while Biden’s foreign policy has achieved positive results in revamping the western alliance and driving global efforts in combating climate change, there is still a need for America to seek out non-traditional allies and foes to try and mend relations through all available avenues for mutually beneficial engagements.

Agwanda is affiliated with the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution, George Mason and the Department of Political Science and International Relations, Marmara University. He holds a masters in International Relations and African Studies and a second masters degree in Conflict Analysis and Resolution. His research interests include conflict analysis and resolution, international security, foreign policy analysis, and critical terrorism studies. He has published several articles in leading international journals and contributed book chapters in edited volumes.