Amid escalating tensions, China’s strategic military reforms under Xi Jinping focus on enhancing the PLA’s regional readiness and asserting its global military presence.

During the last decade, the People’s Republic of China has undertaken a series of structural and technological military reforms that suggest a willingness of Beijing to achieve combat readiness in order to pursue its main geopolitical and economic targets of the century. With the current geopolitical tensions with the West and the complex frontline situation of Moscow in the war in Ukraine, in the last two years, Xi Jinping has prioritized the restructuring and modernization of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), with the main goal of preparing Chinese troops for a possible need for the use of force in the Asia-Pacific regional context. In order to understand the core principles and logic of Beijing’s recent military reforms, an overview of the main strategic and regional priorities for the Chinese government needs to be taken into consideration.

First of all, militarily speaking, until now China remains a regional power, still incapable but also unwilling to project its military power worldwide like the US, whose core military strategy is to maintain the global dominance of the seas and the oceans to protect the American-led trade market and to contain its main geopolitical rivals in their regional spheres of influence. Unlike the US, China seeks to gain regional dominance in regions where Beijing has geopolitical and economic interests: mainly the East China Sea, the South China Sea, and the Taiwan Strait, all areas in which the main maritime routes of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) develop. Not by chance, the only official Chinese military base abroad up to 2024 is in Djibouti, a country located exactly in front of the Bab al-Mandab Strait, which connects the Gulf of Aden with the Red Sea, a crucial route for Chinese goods to arrive in the Mediterranean Sea through the Indian Ocean.

Secondly, Beijing has political issues of reunification with Taiwan and regional tensions with India, Japan, and the Philippines, all countries supported directly or indirectly by the US in its Indo-Pacific strategy, which may include a US direct military intervention in case of its allies conducting a war against China. Therefore, Beijing has a strong interest not to develop a great military force spread worldwide but to focus on building up an effective military capable of outclassing its adversaries, including the US, in limited regional theatres: for instance, in case of a Taiwan invasion or in the context of territorial disputes in the East and South China Seas against Japan, the Philippines, or the ASEAN countries. However, the main military rationale of the PLA forces remains the protection of Chinese trade routes and its territorial integrity and sovereignty, without aspiring to global military dominance.

According to these two main reasons, Beijing has developed a series of reforms of the PLA in the last decade, touching the budget, the doctrines, and the structure of the Chinese military. Regarding the military budget, Chinese military expenditure in 2024 has been ¥1.55 trillion, equivalent to $225 billion USD. It represents around 2% of China’s GDP, much lower compared to the ratio of other great powers, and yet still the second largest military expenditure worldwide after the US due to the massive dimension of the Chinese GDP. Compared to 2023, the increase in the Chinese military budget has been 7.2%, keeping up a long-term trend of annual increases in defense spending.

In order to be capable of competing and winning against any enemy force in the regional seas and regional theaters of war, Xi Jinping, through internal Party and national reforms, now holds the role of chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), the institution that directly supervises everything related to the PLA and commands the entire armed forces. This reform enables a direct and fast command chain, able to provide effective and immediate orders to the armed forces in case of war.

With this streamlined and more immediate command chain, under the Xi administration, the Chinese military has been able to develop its main military doctrine of “Active Defense,” aimed at combining a defensive strategic posture with offensive operational tactics, focused on fast, powerful, and coordinated pre-emptive attacks and defensive operations. This Active Defense doctrine comprises three main features: integrated joint operations, Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) weapons, and civil-military integration.

The integrated joint operations represent the first decisive update of the Chinese military in recent years: it consists of enhanced coordination between the different branches of the Chinese military. In 2015, there was the first major reform of the Chinese armed forces with the distinction of five main forces: the Army, the Navy, the Air Force, the Rocket Force, and the Strategic Support Force (SSF), with the latter having the goal of supporting all the other four in joint coordinated operations. Yet, with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the evident lack of coordination and command capability of the Russian Armed Forces in the first stage of the war, Beijing decided to strengthen the coordination capability of the PLA armed forces, developing the so-called “four services (军种) and four arms (兵种)” structure.

In the last few years, the Army, the Navy, the Air Force, and the Rocket Force (the four services) are now supported by four new “arms” derived from the SSF: the Aerospace Force, the Cyberspace Force, the Information Support Force, and the Joint Logistics Support Force. These new arms focus on space, cyber operations, intelligence, reconnaissance, and surveillance and have been split in order to maximize the coordination, effectiveness, and specificity of tasks during joint operations with the four services of the PLA, thus avoiding the waste of operational time and resources allocation during battle by an alone and ineffective SSF.

The second branch of the Active Defense doctrine is represented by the A2/AD weapons. These weapons are meant to block enemy air force and navy intervention in the Chinese areas of interest in the Western Pacific in case of Chinese involvement in regional conflicts: mainly the East China Sea, the South China Sea, and the Yellow Sea. These weapons include ground and air-launched cruise missiles, short and medium-range ballistic missiles, anti-ship ballistic missiles, hypersonic missiles such as the DF-ZF, advanced fighter aircraft and stealth aircraft like the J-20, naval vessels including aircraft carriers such as the Liaoning and the Shandong, together with submarines, air refueling capabilities, and integrated defense systems. The main priority of these A2/AD weapons is to contain US intervention in case of a Taiwan conflict.

Finally, the third branch of the Active Defense Doctrine is represented by the civil-military integration of the Chinese armed forces, strongly promoted by the CCP. This branch represents the concrete demonstration of the Chinese inheritance of old historical Chinese military doctrines such as The Art of War by Sun Tzu and Mao Zedong’s guerrilla warfare strategy. The core principle of these old war doctrines is to lead the enemy into unfamiliar situations and fight it while it is distracted or when its military capabilities cannot function due to prohibitive environmental and contextual conditions. In the current warfare context, these strategies translate into heavy, systematic, and precise use of civil-related technologies such as artificial intelligence and advanced robotics on the battlefield and elevated and wide use of cyber warfare to disturb, deceive, and disarm the enemy during specific phases and in crucial areas.

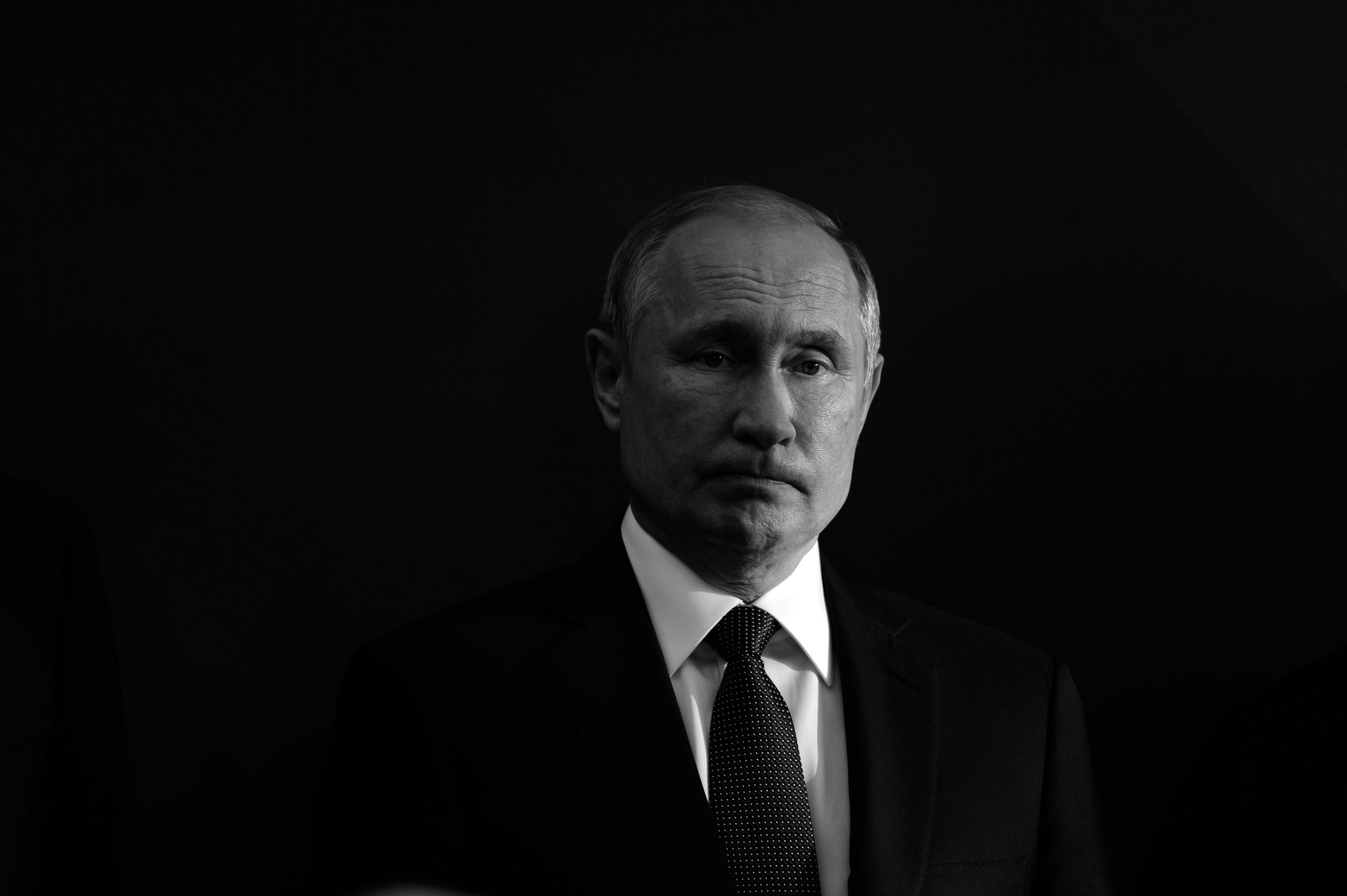

Lastly, but not less importantly, Beijing is intensifying its joint military exercises with important regional allies, especially with Russia. The joint exercises are improving in coordination capabilities, such as the recent coordinated joint air exercise between Russian and Chinese jets and bombers flying in the proximity of the US border in Alaska. Furthermore, China is constantly engaging in combat simulations by organizing drills over the Taiwan Strait, thus improving the combat readiness of the Chinese Air Force.

In conclusion, the Chinese military has witnessed several great reforms in the last decade of Xi Jinping’s presidency: command chain restructure, armed forces reforms, and economic support are all variables to take into account in order to understand the extent of the Chinese military buildup. However, an important point to consider is that China, unlike Russia, is traditionally a conflict-avoiding power: the Active Defense Doctrine represents a mirror of a great power that is not willing to intervene in great and risky war theaters, also shown by the unwillingness of Beijing to use nuclear weapons except in the case of a globally extended conflict that can jeopardize the survival of the state. Nevertheless, China is preparing itself to effectively defend its geopolitical interests in case of external intervention in its domestic and regional priority affairs, such as the BRI, Taiwan, and the de facto control of regional maritime areas in the Western Pacific.

Riccardo Nachtigal is a Master Student in East Asian Studies at University of Groningen, Netherlands. His main fields of studies are Chinese Foreign Policy, Sino-Russian relations, EU-China relations and the Asia-Pacific region.