Not a geopolitical task, but the survival of Russian statehood. Russia’s military adventures from the 1990s to 2025 and probably into the future cast an impression of a “forever war” driven by civilizationalist neo-imperialism. In Western discourse, the conversation focuses on the Kremlin’s unprovoked actions for the Kremlin’s own sake. This seems logical considering the way Russia used manufactured pretexts to sell to the Russian public a justification for aggression. In addition, the ideological legacies from the Cold War live on as the U.S. used tropes of a clash between democracy and autocracy. Yet the broad-brush stroke of labels of “forever war” solely on Russia is problematic. Upon closer inspection, through different perspectives, a more complex reality is revealed. Rather than endless wars, which could be compared to the percentages, Russia and the U.S. have been at peace in their existence; Russian aggression can be presented as a tool for regime security and elite cohesion domestically. By creating narratives and performing certain actions, the Kremlin can preserve its rule, maintain elite loyalty, and maintain domestic order.

This essay seeks to present regime security through a realist-constructivist lens. While constructivists typically use structural realism as a punching bag due to its rationalist assumptions, other scholars have noted that there is quite a bit of overlap between classical realism and constructivism. They synthesize classical realism’s focus on power and security with constructivism’s attention on ideas and identity. This allows one to focus on emotions, values, and externalized beliefs. The thesis presented here is that Russian aggression is about regime security. A comparison of behavior from liberal democratic countries’ own military behavior reveals the role that identity and emotions play in democracies’ engagement in wars with non-democracies. This highlights a double standard in how wars are presented, even when Western military actions are proactive and far-reaching. By reviewing these issues, we can assess that Russian actions are not some unique ideological menace, but a familiar strategy of regime security by a garrison state.

From a realist-constructivist view, it acknowledges that states seek power, and historical narratives, domestic politics, and the perception of cultural threats shape security. This allows us to move beyond the simplistic notion of “just an aggressor.” Sure, Russia is the aggressor. Yet, this perspective recognizes that the Kremlin is attempting to safeguard its regime by using and responding to ideas and narratives. While Russia’s military interventions expand its influence, they are driven not by territorial expansion but by regime preservation, filtered through narratives of threats and national greatness. This approach is taken from works by J. Samuel Barkin, who recognized that classical realism and constructivism share similar assumptions about politics. While realism is associated with material power, realist-constructivists remind us that power is also nonmaterial. This means regimes like Russia’s can legitimize themselves through stories, such as “Russia is a besieged fortress,” encircled by hostile forces, compelled to assert itself. The result is an assertive strategy using ideological justifications for suppression and military action. This allows us to see Russia’s conflicts in a different light by considering they are connected to internal fears and interests, which means the Kremlin’s need to maintain power, order, and loyalty at home.

is doing his PhD at Vytautas Magnus University and teach at LCC International University. His research focuses on grand strategy and foreign policy analysis of Central and Eastern Europe, the USA and Russia.

In addition to the narrative aspect of Russia, the concept of the “garrison state” also gives us insight into how to view Russia. This term refers to when a state feels like it is under constant external threat, it can adapt or adjust its internal politics by concentrating power within the military and security elites. Within a garrison state, political leaders tend to inflate external threats, sell mobilisation, and tighten control. In the case of Russia, there is this siege mentality which refers to NATO expansion, color revolutions, sanctions, and foreign agents as examples of how Russia is threatened and justifies a tighter grip on society. The “forever war” position that Russia and its rhetoric as a civilizational state is not necessarily a grand plan of empire but a reflection of leaders’ determination to survive; essentially, they use war as a means to fortify their regime.

When discussing “forever wars,” it is essential to note that regime security is not just applicable to nondemocracies. Russia is far from the only type of state to engage in proactive military operations justified by grand ideological narratives. Liberal democracies, often the critics of Putin’s wars, have their own history of using force abroad. As Aris Roussinos notes in his article “What Putin and Liberals Share: Both Are Willing to Sacrifice the Nation-State,” he notes that Putin has a liberal reading of nationalist history: “Ukrainian elites, through the logic of seeking their own advancement, created a Ukrainian nation where none had existed before, just as Gellner characterises the ideal nationalism of his fictional Ruritania.” Madison Schramm’s recent study Why Democracies Fight Dictators finds that liberal democracies show a distinct propensity to engage in conflicts with personalist dictatorships. In most cases, it is the liberal democracy that chooses to employ force. We see wars of regime change and nation-building. In addition, with selectorate theory research, liberal democratic leaders can bolster their public opinion and moral narratives by confronting tyrants abroad.

In both cases of Russia and liberal wars, there is a portrayal of the “other” as threatening, irrational, and immoral. The cognitive biases and domestic political narratives shape this view. Leaders and the public are predisposed to respond to authoritarian aggressors with moral outrage and even anger, an emotional response that can increase risk-taking and aggression. Just as democracies see a Hitler in every leader who has authoritarian tendencies or features, in their mind a tyrant must be stopped before it’s too late. This emotional response can be similar to how a state may seek to preserve its ontological security, as previously written about. This mindset can lead to escalation and the initiation of force even when other options exist, because democratic publics rally behind the idea of confronting evil. In particular, these wars are wars of choice against regimes deemed rogue or repressive, in which liberal democracies or Russia are on a mission to save the repressed.

The role of the public in these wars of choice is key. In Russia’s Foreign Policy, Andrei Tsygankov notes the consistent domestic responses of the Russian Federation and how the Kremlin responded to the public. In Serbia (1999), Afghanistan (2001), Iraq (2003), Libya (2011) and other wars illustrate how democracies project force abroad, often framing it as upholding international norms, protecting human rights, spreading democracy, stopping atrocities, or preempting security threats like terrorism or weapons of mass destruction. It is important to recognize that domestic politics and perceptions play a huge role in democratic decisions to go to war. Take for example the Falklands Islands War between the Military Junta in Argentina and the United Kingdom. At the time when the Argentinian military captured the island, Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party was behind in the domestic polls.

In addition to the narrative aspect of Russia, the concept of the “garrison state” also gives us insight into how to view Russia. This term refers to when a state feels like it is under constant external threat, it can adapt or adjust its internal politics by concentrating power within the military and security elites. Within a garrison state, political leaders tend to inflate external threats, sell mobilisation, and tighten control. In the case of Russia, there is this siege mentality which refers to NATO expansion, color revolutions, sanctions, and foreign agents as examples of how Russia is threatened and justifies a tighter grip on society. The “forever war” position that Russia and its rhetoric as a civilizational state is not necessarily a grand plan of empire but a reflection of leaders’ determination to survive; essentially, they use war as a means to fortify their regime.

When discussing “forever wars,” it is essential to note that regime security is not just applicable to nondemocracies. Russia is far from the only type of state to engage in proactive military operations justified by grand ideological narratives. Liberal democracies, often the critics of Putin’s wars, have their own history of using force abroad. As Aris Roussinos notes in his article “What Putin and Liberals Share: Both Are Willing to Sacrifice the Nation-State,” he notes that Putin has a liberal reading of nationalist history: “Ukrainian elites, through the logic of seeking their own advancement, created a Ukrainian nation where none had existed before, just as Gellner characterises the ideal nationalism of his fictional Ruritania.” Madison Schramm’s recent study Why Democracies Fight Dictators finds that liberal democracies show a distinct propensity to engage in conflicts with personalist dictatorships. In most cases, it is the liberal democracy that chooses to employ force. We see wars of regime change and nation-building. In addition, with selectorate theory research, liberal democratic leaders can bolster their public opinion and moral narratives by confronting tyrants abroad.

In both cases of Russia and liberal wars, there is a portrayal of the “other” as threatening, irrational, and immoral. The cognitive biases and domestic political narratives shape this view. Leaders and the public are predisposed to respond to authoritarian aggressors with moral outrage and even anger, an emotional response that can increase risk-taking and aggression. Just as democracies see a Hitler in every leader who has authoritarian tendencies or features, in their mind a tyrant must be stopped before it’s too late. This emotional response can be similar to how a state may seek to preserve its ontological security, as previously written about. This mindset can lead to escalation and the initiation of force even when other options exist, because democratic publics rally behind the idea of confronting evil. In particular, these wars are wars of choice against regimes deemed rogue or repressive, in which liberal democracies or Russia are on a mission to save the repressed.

The role of the public in these wars of choice is key. In Russia’s Foreign Policy, Andrei Tsygankov notes the consistent domestic responses of the Russian Federation and how the Kremlin responded to the public. In Serbia (1999), Afghanistan (2001), Iraq (2003), Libya (2011) and other wars illustrate how democracies project force abroad, often framing it as upholding international norms, protecting human rights, spreading democracy, stopping atrocities, or preempting security threats like terrorism or weapons of mass destruction. It is important to recognize that domestic politics and perceptions play a huge role in democratic decisions to go to war. Take for example the Falklands Islands War between the Military Junta in Argentina and the United Kingdom. At the time when the Argentinian military captured the island, Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party was behind in the domestic polls.

Thatcher’s personal approval went from about 29% in February 1982 to 44% in May, peaking at 52% in July. Similarly, support for the Conservative Party grew from 27% to 41% after the conflict began. Before the war, the polling reflected economic dissatisfaction with her government, but Bueno de Mesquita’s literature shows that such war can act as a distraction from domestic troubles. This means international conflict can lead to a rally-around-the-flag effect and political reward at home. The Conservative Party won 42.4% of the national vote, securing 397 seats. Democratic leaders, answerable to voters, are keenly aware that standing up to a foreign dictator can boost their popularity at home. Being seen as appeasing or surrendering to a tyrant can be politically damaging. Thus, governments also sometimes find warfare useful for domestic cohesion or distraction, even if cloaked in noble language. With this context, Russia’s “forever war” is less about grand ideological expansion than it is about Vladimir Putin’s regime security. The Kremlin’s wars serve to shore up domestic control and legitimacy. The Russians constantly make references to the Second Patriotic War, which is the height of Russian status and recognition.

From the Kremlin’s perspective, the recurring external crises or wars are not unwanted accidents but politically useful tools. The Kremlin has repeatedly manufactured or inflated security threats to invoke a rally-around-the-flag effect in attempts to secure control. Some argue the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 was a preventive measure against domestic dissent. The war united the forces and brought unity among the elites, distracting the public from economic issues. Additionally, the war allows the Kremlin to tighten control domestically by justifying harsher internal measures and silencing opposition in the name of national survival. Websites and apps are banned, and messages are scanned for wrongthink. As the Wilson Center’s Timothy Frye notes: “In response, the United States levied economic sanctions against Russia on 6 March 2014.

Approval ratings for the Russian leadership then soared and remained high for more than four years… most groups increased their support for the Russian government when reminded about the annexation of Crimea, including respondents who were initially skeptical of President Putin and those who were experiencing economic hardship.” The Atlantic Council’s Maria Snegovaya notes how in 2022, “public optimism and pride soared. They have remained high, as evidenced by the finding that average Russians are now significantly more likely to believe their country is headed in the right direction. Furthermore, views of Russia’s economic, social, and political priorities shifted toward a siege mentality with a sense of grievance vis-à-vis the West.”

There is potential here for an insecurity loop to form. The reason is that it creates a self-reinforcing cycle. Threats are inflated to gain support, and that support enables more aggressive actions that incur new threats. In the short term, the strategy strengthens the Kremlin and weakens the opposition. Even the opposition has supported Russia’s wars. It allows the regime to reshuffle elites and resources under wartime urgency while postponing any real political competition. Each foreign venture provides only temporary reprieve from domestic unease, requiring yet another conflict or confrontation to sustain the drumbeat of unity. As a result, the Russian state remains in perpetual mobilization mode. As mentioned in my last piece, there is an ontological security aspect to Russian security. Putin says, “For us, this is not a geopolitical task, but a task of the survival of Russian statehood…” This is framing the war as an existential battle for survival.

Like a feudal system, the ruler distributes rewards and resources to those who demonstrate loyalty.

To help with this narrative, the state deploys narratives that it is defending Russian culture, identity, and traditional values to justify the war economy and repression. This story paints Russia as being locked into a civilizational struggle against a predatory “collective West.” In addition, the state propaganda feeds off nostalgia for the Great Patriotic War. This links to a continuation of the heroic fight against fascism and annihilation. Within this logic, war is essential to national survival. If Russia doesn’t fight back, its unique civilization will be subsumed or destroyed by outside forces. To ground this narrative, the state propaganda links societal roles to patriotism. Schools have had students dress in white army uniforms and have added “patriotic” lessons to the school curriculum. In universities, there are lessons on the “Fundamentals of Russian Statehood.” This embedding of schooling, cultural, and even religious rhetoric (a holy war against satanic liberalism) helps construct a societal narrative and perception of the war in the public. The defense of the “Russian World,” Orthodox faith, traditional family, and ethnic Russians can be presented as a noble cause within the public’s eyes.

This appeal to patriotic duty coincides with law enforcement. Russia has a tight surveillance state that monitors online activity and is ready to be used against dissent or behavior that would be representative of the “collective West.” Laws similar to cancel-culture or hate-speech laws were created barring anything that discredits the military or spreads “false information” about the special military operation. These laws can have a punishment of up to 15 years. This makes sense within the context that the Kremlin is trying to project. It sees itself as a state under siege. This type of thinking is widespread amongst the law enforcement and security services. Like when the police can arrest someone for holding a blank sign. The coercive pressure on domestic life helps keep opposition atomized, muted, and at manageable levels. Social media is now limited to approved apps and is monitored. The state is seeking to normalize life on a war footing, which has them tolerate repressions and economic struggles. Suppressing dissent and instilling caution in the populace allows the state to avoid immediate scrutiny of its use of force.

Parallel to a tighter control, the Putin system wields the tool of ideological control to maintain unity in key institutions. Something similar to political commissars has returned; these were people who were embedded within the ranks to ensure everyone follows the party line. In 2018, a “military-political” directorate within the Russian army was formed to promote patriotism. This was due to “conditions of a global information and psychological confrontation (with the West) the role of political and moral unity within the army and society has drastically grown.” The main point is that the Kremlin revived the Soviet-style political officers to keep the army ideologically aligned.

Yet beneath these mechanisms to maintain control lies a more informal but no less powerful force, the blat system. This system is similar to that of feudal lords because it is about patronage and personal loyalty. Jeff Hawn at the New Lines Institute compared Putin’s system to that of House of Cards because it shows how overlapping informal networks of favors and influence saturate politics and business. Like a feudal system, the ruler distributes rewards and resources to those who demonstrate loyalty. This informal system allows the state to formally have budgets and sign contracts to regions and bureaucrats, to indirectly become lucrative kickbacks, sweetheart deals, and mutual back-scratching deals. By rewarding loyalty and removing people who do not demonstrate loyalty, this informal system forms a carrot-and-stick arrangement which keeps the elites and oligarchs invested in the status quo.

There are several takeaways from applying realist-constructivism to Russia’s quest for regime security. The first is that war is a tool for elite cohesion. Authoritarian regimes use war to tighten their inner circles. As military, security, and business figures feel invested in the system, they are less likely to defect from the regime. This cohesion keeps the elite tight enough to maintain the system. This allows for domestic legitimacy not just for the elites but for the domestic audience as well. By framing the invasion of Ukraine as an existential defense of Russia, the Kremlin can rally public support regardless of the financial costs and loss of life. The patriotic and civilizational narratives enable harsh sacrifices in the name of survival. External threats and sanctions may have little effect on a regime that utilizes the siege discourse. Sure, over time, there will be enough pain that some will not tolerate it. The Kremlin can spin the sanctions and NATO opposition into proof of an ongoing war against Russia. The long game against a system such as this involves patience, information strategies that counter false narratives, and reaching out to elites to change course.

In conclusion, Russia is engaging in a war for regime security, not as a grand ideological crusade or simple land-grab. Russia, as a garrison state, develops threats to justify military expansion and repression at home. The Kremlin frames conflicts as existential battles for the nation’s survival. This is a narrative that positions the Kremlin as the defender of the state against a siege. By looking through the regime security concept, we can explain Russia’s aggression. War is a tool of the Kremlin to fortify its rule and preempt vulnerabilities.

The combination of power politics and identity narrative is what J. Samuel Barkin’s realist-constructivist theory would assume. This theory bridges material and ideational explanations, which allows for the consideration of how ideas, norms, and identities influence states’ objectives. In Russia’s case, the quest for regime security is blended with ideological performance. By this I mean the Kremlin has material power in the form of tanks and a security apparatus, and it has discursive power with the use of historical myths. Power is not just a material object; it is also legitimacy, morale, and meaning. This combination of power allows the Kremlin to develop a narrative of Russia as a besieged fortress. This narrative allows the reinforcement of the domestic authority the state has, as well as justifying actions that would be otherwise aggressive.

Ultimately, viewing Russia as a garrison state through a realist-constructivist lens reveals a stark but useful truth. The state is fighting to secure its rule at all costs, with side quests being mystical destiny or opportunistic land grabs. Russian state power comes in two forms: a rifle barrel and a story. By understanding how material coercion and nationalistic mythmaking reinforce each other in Russia’s strategy, we can gain a deeper understanding of why this war, and others like it, persist. This reminds us that even in a world of high ideals, wars are fundamentally political acts, forged in a blend of fear, interest, and identity, by appreciating the logic of regime security in the Kremlin’s siege rhetoric, we can better grasp the roots of its behavior. That discourse means oppositional forces must address the vulnerabilities of the Russian state, provide a coherent dialogue about values with credibility, and avoid mirroring the very narratives we seek to dispel.

Thatcher’s personal approval went from about 29% in February 1982 to 44% in May, peaking at 52% in July. Similarly, support for the Conservative Party grew from 27% to 41% after the conflict began. Before the war, the polling reflected economic dissatisfaction with her government, but Bueno de Mesquita’s literature shows that such war can act as a distraction from domestic troubles. This means international conflict can lead to a rally-around-the-flag effect and political reward at home. The Conservative Party won 42.4% of the national vote, securing 397 seats. Democratic leaders, answerable to voters, are keenly aware that standing up to a foreign dictator can boost their popularity at home. Being seen as appeasing or surrendering to a tyrant can be politically damaging. Thus, governments also sometimes find warfare useful for domestic cohesion or distraction, even if cloaked in noble language. With this context, Russia’s “forever war” is less about grand ideological expansion than it is about Vladimir Putin’s regime security. The Kremlin’s wars serve to shore up domestic control and legitimacy. The Russians constantly make references to the Second Patriotic War, which is the height of Russian status and recognition.

From the Kremlin’s perspective, the recurring external crises or wars are not unwanted accidents but politically useful tools. The Kremlin has repeatedly manufactured or inflated security threats to invoke a rally-around-the-flag effect in attempts to secure control. Some argue the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 was a preventive measure against domestic dissent. The war united the forces and brought unity among the elites, distracting the public from economic issues. Additionally, the war allows the Kremlin to tighten control domestically by justifying harsher internal measures and silencing opposition in the name of national survival. Websites and apps are banned, and messages are scanned for wrongthink. As the Wilson Center’s Timothy Frye notes: “In response, the United States levied economic sanctions against Russia on 6 March 2014.

Approval ratings for the Russian leadership then soared and remained high for more than four years… most groups increased their support for the Russian government when reminded about the annexation of Crimea, including respondents who were initially skeptical of President Putin and those who were experiencing economic hardship.” The Atlantic Council’s Maria Snegovaya notes how in 2022, “public optimism and pride soared. They have remained high, as evidenced by the finding that average Russians are now significantly more likely to believe their country is headed in the right direction. Furthermore, views of Russia’s economic, social, and political priorities shifted toward a siege mentality with a sense of grievance vis-à-vis the West.”

There is potential here for an insecurity loop to form. The reason is that it creates a self-reinforcing cycle. Threats are inflated to gain support, and that support enables more aggressive actions that incur new threats. In the short term, the strategy strengthens the Kremlin and weakens the opposition. Even the opposition has supported Russia’s wars. It allows the regime to reshuffle elites and resources under wartime urgency while postponing any real political competition. Each foreign venture provides only temporary reprieve from domestic unease, requiring yet another conflict or confrontation to sustain the drumbeat of unity. As a result, the Russian state remains in perpetual mobilization mode. As mentioned in my last piece, there is an ontological security aspect to Russian security. Putin says, “For us, this is not a geopolitical task, but a task of the survival of Russian statehood…” This is framing the war as an existential battle for survival.

To help with this narrative, the state deploys narratives that it is defending Russian culture, identity, and traditional values to justify the war economy and repression. This story paints Russia as being locked into a

civilizational struggle against a predatory “collective West.” In addition, the state propaganda feeds off nostalgia for the Great Patriotic War. This links to a continuation of the heroic fight against fascism and annihilation. Within this logic, war is essential to national survival. If Russia doesn’t fight back, its unique civilization will be subsumed or destroyed by outside forces. To ground this narrative, the state propaganda links societal roles to patriotism. Schools have had students dress in white army uniforms and have added “patriotic” lessons to the school curriculum. In universities, there are lessons on the “Fundamentals of Russian Statehood.” This embedding of schooling, cultural, and even religious rhetoric (a holy war against satanic liberalism) helps construct a societal narrative and perception of the war in the public. The defense of the “Russian World,” Orthodox faith, traditional family, and ethnic Russians can be presented as a noble cause within the public’s eyes.

This appeal to patriotic duty coincides with law enforcement. Russia has a tight surveillance state that monitors online activity and is ready to be used against dissent or behavior that would be representative of the “collective West.” Laws similar to cancel-culture or hate-speech laws were created barring anything that discredits the military or spreads “false information” about the special military operation. These laws can have a punishment of up to 15 years. This makes sense within the context that the Kremlin is trying to project. It sees itself as a state under siege. This type of thinking is widespread amongst the law enforcement and security services. Like when the police can arrest someone for holding a blank sign. The coercive pressure on domestic life helps keep opposition atomized, muted, and at manageable levels. Social media is now limited to approved apps and is monitored. The state is seeking to normalize life on a war footing, which has them tolerate repressions and economic struggles. Suppressing dissent and instilling caution in the populace allows the state to avoid immediate scrutiny of its use of force.

Parallel to a tighter control, the Putin system wields the tool of ideological control to maintain unity in key institutions. Something similar to political commissars has returned; these were people who were embedded within the ranks to ensure everyone follows the party line. In 2018, a “military-political” directorate within the Russian army was formed to promote patriotism. This was due to “conditions of a global information and psychological confrontation (with the West) the role of political and moral unity within the army and society has drastically grown.” The main point is that the Kremlin revived the Soviet-style political officers to keep the army ideologically aligned.

Yet beneath these mechanisms to maintain control lies a more informal but no less powerful force, the blat system. This system is similar to that of feudal lords because it is about patronage and personal loyalty. Jeff Hawn at the New Lines Institute compared Putin’s system to that of House of Cards because it shows how overlapping informal networks of favors and influence saturate politics and business. Like a feudal system, the ruler distributes rewards and resources to those who demonstrate loyalty. This informal system allows the state to formally have budgets and sign contracts to regions and bureaucrats, to indirectly become lucrative kickbacks, sweetheart deals, and mutual back-scratching deals. By rewarding loyalty and removing people who do not demonstrate loyalty, this informal system forms a carrot-and-stick arrangement which keeps the elites and oligarchs invested in the status quo.

There are several takeaways from applying realist-constructivism to Russia’s quest for regime security. The first is that war is a tool for elite cohesion. Authoritarian regimes use war to tighten their inner circles. As military, security, and business figures feel invested in the system, they are less likely to defect from the regime. This cohesion keeps the elite tight enough to maintain the system. This allows for domestic legitimacy not just for the elites but for the domestic audience as well. By framing the invasion of Ukraine as an existential defense of Russia, the Kremlin can rally public support regardless of the financial costs and loss of life. The patriotic and civilizational narratives enable harsh sacrifices in the name of survival. External threats and sanctions may have little effect on a regime that utilizes the siege discourse. Sure, over time, there will be enough pain that some will not tolerate it. The Kremlin can spin the sanctions and NATO opposition into proof of an ongoing war against Russia. The long game against a system such as this involves patience, information strategies that counter false narratives, and reaching out to elites to change course.

In conclusion, Russia is engaging in a war for regime security, not as a grand ideological crusade or simple land-grab. Russia, as a garrison state, develops threats to justify military expansion and repression at home. The Kremlin frames conflicts as existential battles for the nation’s survival. This is a narrative that positions the Kremlin as the defender of the state against a siege. By looking through the regime security concept, we can explain Russia’s aggression. War is a tool of the Kremlin to fortify its rule and preempt vulnerabilities.

The combination of power politics and identity narrative is what J. Samuel Barkin’s realist-constructivist theory would assume. This theory bridges material and ideational explanations, which allows for the consideration of how ideas, norms, and identities influence states’ objectives. In Russia’s case, the quest for regime security is blended with ideological performance. By this I mean the Kremlin has material power in the form of tanks and a security apparatus, and it has discursive power with the use of historical myths. Power is not just a material object; it is also legitimacy, morale, and meaning. This combination of power allows the Kremlin to develop a narrative of Russia as a besieged fortress. This narrative allows the reinforcement of the domestic authority the state has, as well as justifying actions that would be otherwise aggressive.

Ultimately, viewing Russia as a garrison state through a realist-constructivist lens reveals a stark but useful truth. The state is fighting to secure its rule at all costs, with side quests being mystical destiny or opportunistic land grabs. Russian state power comes in two forms: a rifle barrel and a story. By understanding how material coercion and nationalistic mythmaking reinforce each other in Russia’s strategy, we can gain a deeper understanding of why this war, and others like it, persist. This reminds us that even in a world of high ideals, wars are fundamentally political acts, forged in a blend of fear, interest, and identity, by appreciating the logic of regime security in the Kremlin’s siege rhetoric, we can better grasp the roots of its behavior. That discourse means oppositional forces must address the vulnerabilities of the Russian state, provide a coherent dialogue about values with credibility, and avoid mirroring the very narratives we seek to dispel.

Recommended

How Warsaw and Kyiv Anchor Europe’s Defense

Trump’s America and the End of Global Trust

U.S. Foreign Policy as a Debate Without End

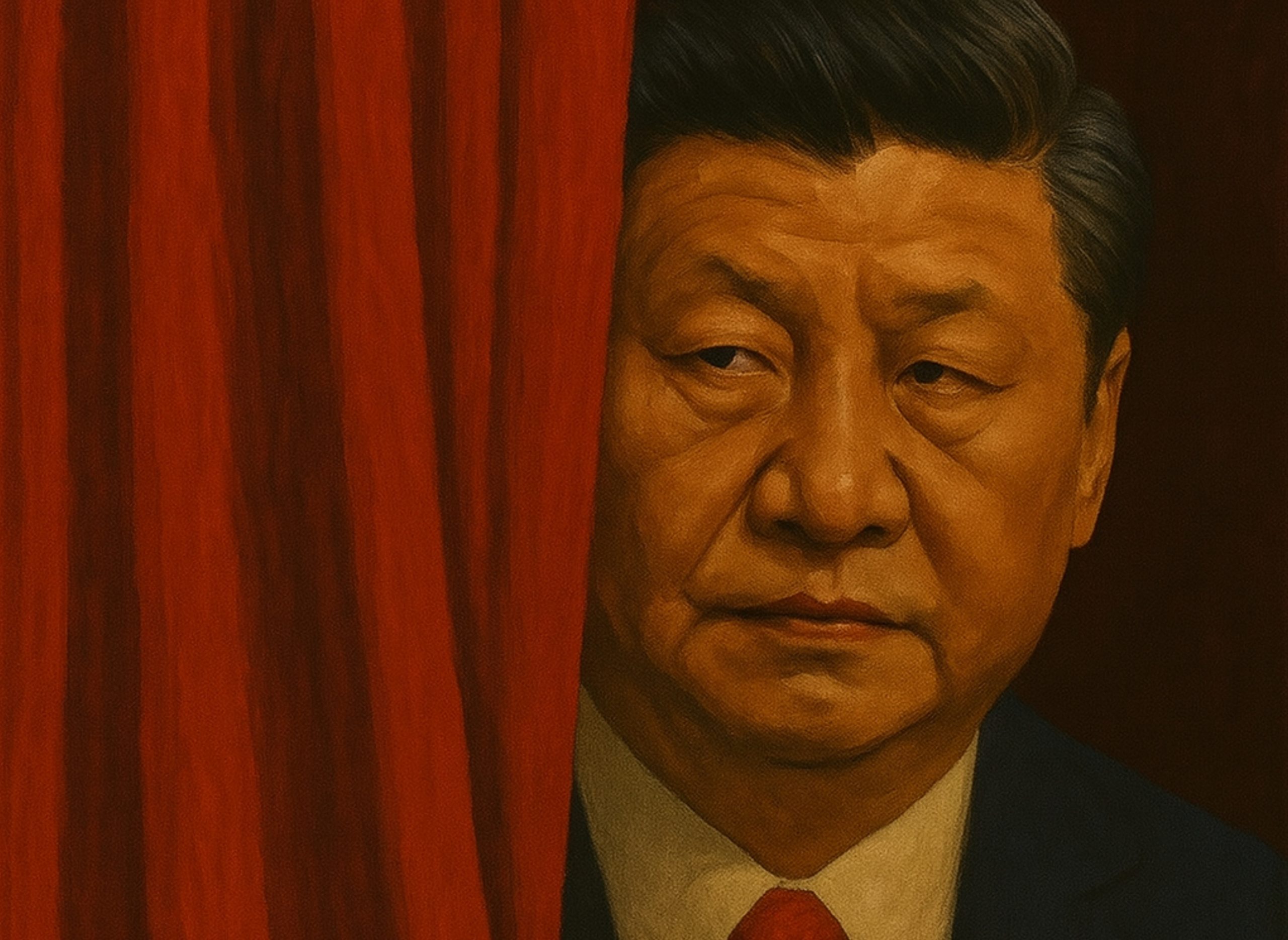

How Xi Jinping Is Shaping China and the World?

The Last Ayatollah