This illustration has been creaed by AI to use only in this article.

On April 26, 2007, former Senator Mike Gravel, while running for president within the Democratic primaries, was asked what his potential administration’s policies would be towards Iraq. Up until this point, America had been occupying portions of Iraq following our 2003 invasion of the country, with thousands of American soldiers being stationed in areas which were rather dangerous and insecure.

Quagmire and insurgency had become a rather persistent problem since our initial victory over Saddam Hussein, and despite new goals, tactics, and even military leaders, all of these attempted solutions failed to mitigate any of the region’s underlying structural issues. We were not greeted as liberators, democracy had not been swiftly delivered, and thousands of Americans had died for very little material gain. Many Americans were outraged, and some of this brewing anger eventually managed to find itself being expressed on a debate stage. Gravel’s response was blunt: “I gotta tell you, we should just plain get out—it’s their country, they’re asking us to leave, and we insist on staying there! And why not get out?”

Most of the hand-selected audience wasn’t interested in Gravel’s argument for more restraint, nor were any of the major candidates on stage. Smiles and laughs followed Gravel’s comments rather than open rejection or debate, conveying a deep sense of shared humor and skepticism for Gravel’s vision of limited foreign intervention. No major candidate, be it Republican or Democratic, was interested in what Gravel and other gadflies had to say, and by the end of the election cycle, very little of the anti-war fervor had moved beyond temporal backlash against the Iraq War. International intervention wasn’t the problem; rather, it was just the way it was being led and delivered.

Jump forward to today, and Gravel’s comments no longer seem so silly or humorous. Americans are increasingly against foreign interventions, such as with the current opposition to a potential war in Venezuela. Similarly, growing numbers of Americans have found themselves opposing aid to both Ukraine and Israel, signaling yet another area of discontent and frustration.

The United States, in a multipolar world, cannot limitlessly expand its commitments and interventions. Eventually, something will give as imperial fatigue sets in, and as foreign adventurism yet again turns into a series of crises and disasters. Put simply, what is occurring among the U.S. population is not exactly new, but it is indeed taking on an interesting flavor.

is a freelance writer who received his Master’s in International Affairs from Indiana University. His areas of focused are comparative political economy, US foreign policy, and international governance.

On April 26, 2007, former Senator Mike Gravel, while running for president within the Democratic primaries, was asked what his potential administration’s policies would be towards Iraq. Up until this point, America had been occupying portions of Iraq following our 2003 invasion of the country, with thousands of American soldiers being stationed in areas which were rather dangerous and insecure.

Quagmire and insurgency had become a rather persistent problem since our initial victory over Saddam Hussein, and despite new goals, tactics, and even military leaders, all of these attempted solutions failed to mitigate any of the region’s underlying structural issues. We were not greeted as liberators, democracy had not been swiftly delivered, and thousands of Americans had died for very little material gain. Many Americans were outraged, and some of this brewing anger eventually managed to find itself being expressed on a debate stage. Gravel’s response was blunt: “I gotta tell you, we should just plain get out—it’s their country, they’re asking us to leave, and we insist on staying there! And why not get out?”

Most of the hand-selected audience wasn’t interested in Gravel’s argument for more restraint, nor were any of the major candidates on stage. Smiles and laughs followed Gravel’s comments rather than open rejection or debate, conveying a deep sense of shared humor and skepticism for Gravel’s vision of limited foreign intervention. No major candidate, be it Republican or Democratic, was interested in what Gravel and other gadflies had to say, and by the end of the election cycle, very little of the anti-war fervor had moved beyond temporal backlash against the Iraq War. International intervention wasn’t the problem; rather, it was just the way it was being led and delivered.

Jump forward to today, and Gravel’s comments no longer seem so silly or humorous. Americans are increasingly against foreign interventions, such as with the current opposition to a potential war in Venezuela. Similarly, growing numbers of Americans have found themselves opposing aid to both Ukraine and Israel, signaling yet another area of discontent and frustration.

The United States, in a multipolar world, cannot limitlessly expand its commitments and interventions. Eventually, something will give as imperial fatigue sets in, and as foreign adventurism yet again turns into a series of crises and disasters. Put simply, what is occurring among the U.S. population is not exactly new, but it is indeed taking on an interesting flavor.

is a freelance writer who received his Master’s in International Affairs from Indiana University. His areas of focused are comparative political economy, US foreign policy, and international governance.

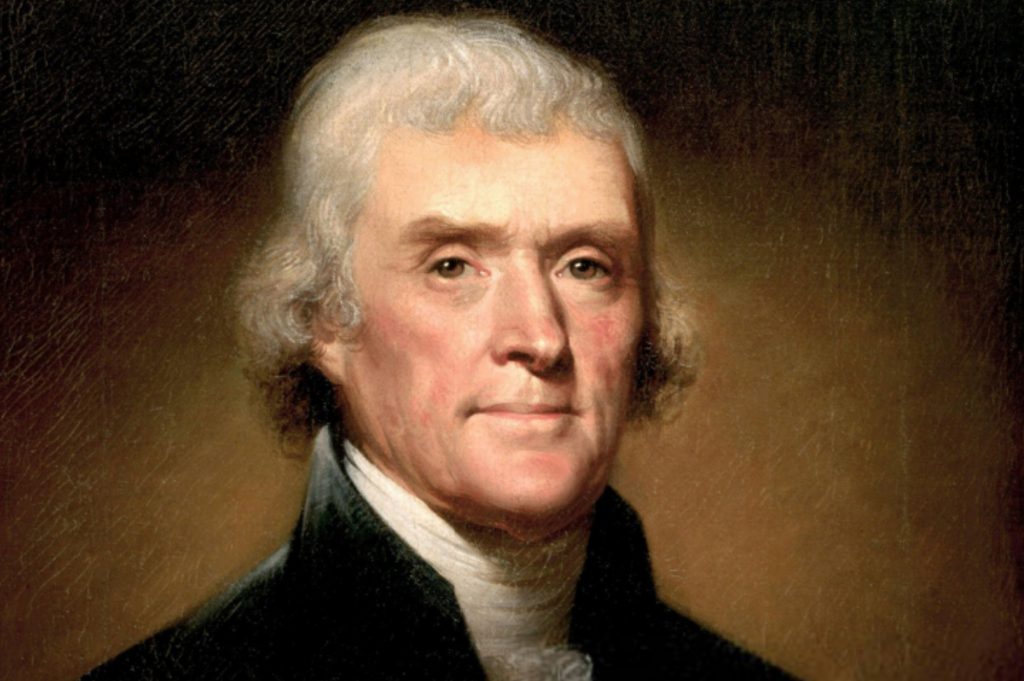

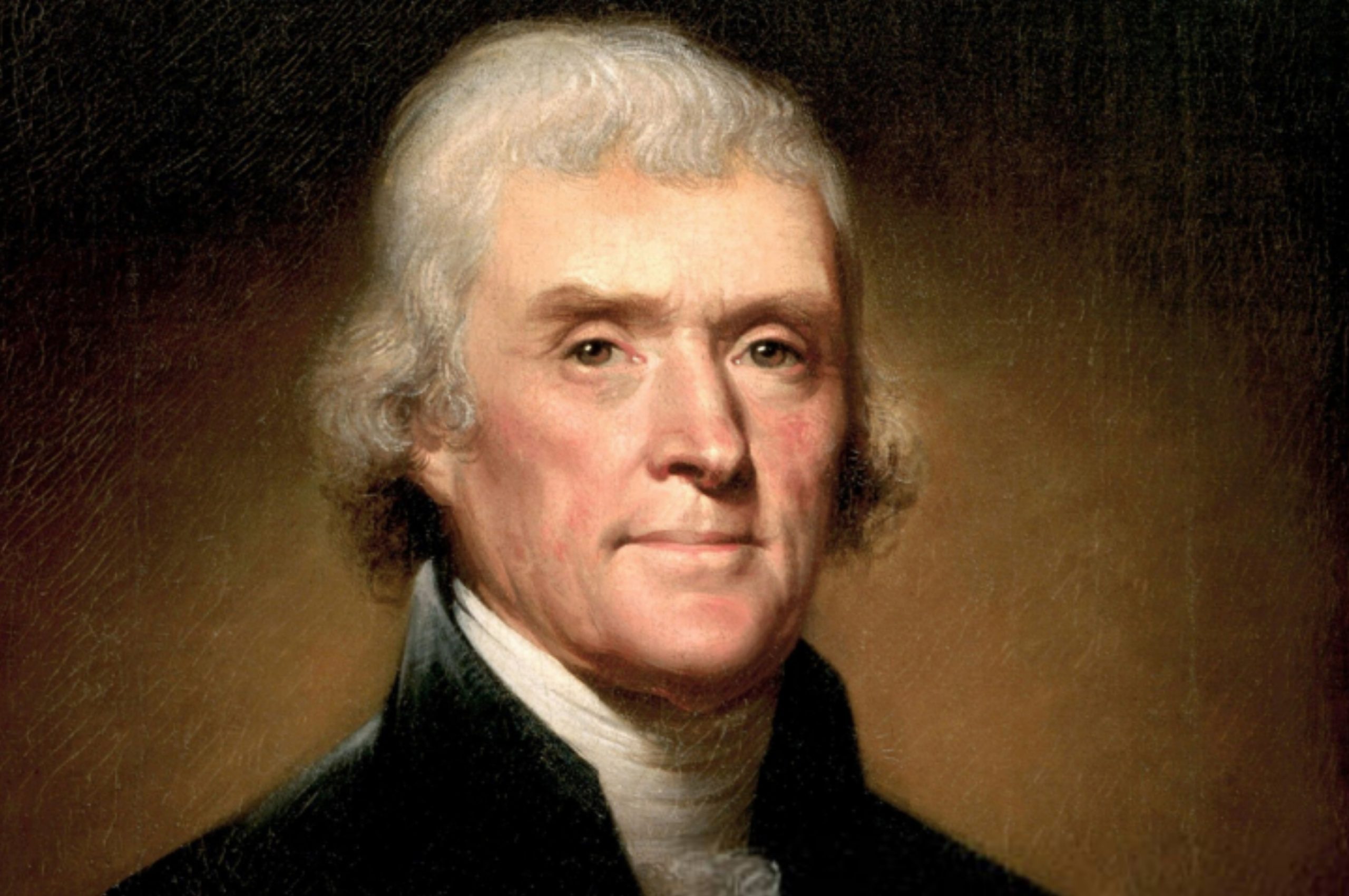

Our growing desire for restraint and focus on the homefront is yet another example of America’s on-again-off-again relationship with Jeffersonian foreign policy. This reemergence of Jefferson’s tradition, passed down through various parties, groups, and individuals, is indeed significant, as are its potential consequences for foreign policymaking writ large. Further, in our increasingly competitive world, something different will eventually have to drive U.S. foreign policy as conditions change and sources of power no longer hold as strong. As we delve deeper into the 21st century, change is indeed occurring, and in the United States, it is a Jeffersonian vision which is seemingly gaining ground faster than any of its competitors.

No Monsters to Destroy

Jeffersonianism began within the mind of the 3rd President of the United States, Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson, who wrote the Declaration of Independence and served as a fundamental figure in early American politics, was a son of the planter class and received an education and upbringing which was different from most Americans. He was well-read, having studied history, mathematics, and philosophy during his time at William and Mary, and was also well-traveled, especially from his ventures in France and Western Europe. Jefferson, the man, was indeed impressive, as was the titular ideology he constructed through his various writings and publications. But it is important to note that Jeffersonianism was not purely based around Jefferson and his career.

Just as with any individual, Jefferson’s outlook for the world was shaped by material conditions and a plethora of entrenched narratives. He stood on the shoulders of both planters and philosophers, statesmen and revolutionaries, and came to develop a worldview that adapted these realities to changing political events. Jefferson’s philosophy, while influential, was not exactly unique just to himself and instead represented a broad and rather inevitable elite political backlash against the excesses of British imperialism in North America.

America’s colonial gentry, composed largely of planters and merchants, led this backlash and witnessed firsthand just how disruptive imperial conflicts could be for both business and general tranquility. Vast imperial wars were followed by economic coercion, mercantilist policies, and an ever more expansive state presence. Taxes were high, western expansion was halted, trade was constricted, and slavery’s survival as an institution seemed to be in question. What were once fundamentals of colonial political economy now seemed quite tenuous, and as these conditions only became more restrictive, this helped to further push American elites toward different ends.

It is within these conditions where Jefferson and his ilk developed their views on political economy and foreign policy. Domestically, they longed for a country where strong individual rights, especially those around property, would be guaranteed by a limited federal government which was to be regulated by various checks and balances. Government, above all else, needed to be restricted in its ability to impose restrictions on individuals and their right to engage in commerce. The end goal of this project, beyond just political independence from Britain, was to cement in place a polity where individual farmers and planters could venture out west in search of abundant land and self-sufficiency. It was to be a country free of monarchs, aristocrats, mercantilist monopolies, and any other form of state-sanctioned hierarchy. It was, put simply, to be a country of free men, free land, and free expansion.

With regard to foreign relations, Jefferson and his class demanded an end to foreign entanglements, alliances, and proxies. Rather than asserting imperial domains or claims, America was to become a global vehicle for freedom. It would soon morph into an “empire of liberty,” focused on delivering republicanism, agricultural freedom, and examples of good governance to all nearby imperials or political ne’er-do-wells.

Our growing desire for restraint and focus on the homefront is yet another example of America’s on-again-off-again relationship with Jeffersonian foreign policy. This reemergence of Jefferson’s tradition, passed down through various parties, groups, and individuals, is indeed significant, as are its potential consequences for foreign policymaking writ large. Further, in our increasingly competitive world, something different will eventually have to drive U.S. foreign policy as conditions change and sources of power no longer hold as strong. As we delve deeper into the 21st century, change is indeed occurring, and in the United States, it is a Jeffersonian vision which is seemingly gaining ground faster than any of its competitors.

No Monsters to Destroy

Jeffersonianism began within the mind of the 3rd President of the United States, Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson, who wrote the Declaration of Independence and served as a fundamental figure in early American politics, was a son of the planter class and received an education and upbringing which was different from most Americans. He was well-read, having studied history, mathematics, and philosophy during his time at William and Mary, and was also well-traveled, especially from his ventures in France and Western Europe. Jefferson, the man, was indeed impressive, as was the titular ideology he constructed through his various writings and publications. But it is important to note that Jeffersonianism was not purely based around Jefferson and his career.

Just as with any individual, Jefferson’s outlook for the world was shaped by material conditions and a plethora of entrenched narratives. He stood on the shoulders of both planters and philosophers, statesmen and revolutionaries, and came to develop a worldview that adapted these realities to changing political events. Jefferson’s philosophy, while influential, was not exactly unique just to himself and instead represented a broad and rather inevitable elite political backlash against the excesses of British imperialism in North America.

America’s colonial gentry, composed largely of planters and merchants, led this backlash and witnessed firsthand just how disruptive imperial conflicts could be for both business and general tranquility. Vast imperial wars were followed by economic coercion, mercantilist policies, and an ever more expansive state presence. Taxes were high, western expansion was halted, trade was constricted, and slavery’s survival as an institution seemed to be in question. What were once fundamentals of colonial political economy now seemed quite tenuous, and as these conditions only became more restrictive, this helped to further push American elites toward different ends.

It is within these conditions where Jefferson and his ilk developed their views on political economy and foreign policy. Domestically, they longed for a country where strong individual rights, especially those around property, would be guaranteed by a limited federal government which was to be regulated by various checks and balances. Government, above all else, needed to be restricted in its ability to impose restrictions on individuals and their right to engage in commerce. The end goal of this project, beyond just political independence from Britain, was to cement in place a polity where individual farmers and planters could venture out west in search of abundant land and self-sufficiency. It was to be a country free of monarchs, aristocrats, mercantilist monopolies, and any other form of state-sanctioned hierarchy. It was, put simply, to be a country of free men, free land, and free expansion.

With regard to foreign relations, Jefferson and his class demanded an end to foreign entanglements, alliances, and proxies. Rather than asserting imperial domains or claims, America was to become a global vehicle for freedom. It would soon morph into an “empire of liberty,” focused on delivering republicanism, agricultural freedom, and examples of good governance to all nearby imperials or political ne’er-do-wells.

From its inception, Jeffersonianism, beyond the mere thoughts or criticisms of just one man, was a regional class project, designed by elite planters and shaped by a vehement reaction against British colonial overreach. In essence, it was an attempt to construct a new paradigm where state power was limited, agriculture was king, expansion was fundamental, and foreign relations were solved through “peaceable coercion[s].”

George Washington emerged from this milieu and quite famously gave a speech where he warned of entangling alliances and the threats of partisanship. Once in office, Jefferson also grew to adopt Washington’s line, especially as his once-admired France became plagued by Napoleon Bonaparte’s despotism. President after president came to adopt these Jeffersonian class principles in stride, and as America emerged into the 1810s and 1820s, alliances were largely avoided in favor of expansion and internal improvements.

As Jeffersonianism came to be interpreted by new generations of elites and political actors, however, mutations began to occur. Domestically, the growing desire for western expansion and yeoman farming became increasingly bogged down by a growing divide between America’s sectional economies. Northern farmers viewed Jeffersonianism’s promise as being anti-slavery and pro-free labor; Southerners viewed slavery and the protection of their property as being a fundamental purpose of government. Soon, Jeffersonianism’s promise of tight-knit rural communities became increasingly impossible as both sectional conflict and growing industrialization came to define 19th-century development.

Concurrently, on the foreign front, Jeffersonianism’s aversion to imperial war and foreign entanglement remained quite present and also rather pertinent as America continued to expand westward. Anti-war sentiment first emerged as America’s conquest of the west brought war with both Mexico and various Native American tribes. It was during the buildup to these contentious decades and conflicts where John Quincy Adams famously stated that “But she [America] goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.”

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, these Jeffersonian reactions repeatedly emerged during moments of intense polarization and imperial conquest. It emerged during our war with Mexico; it emerged as the Gilded Age generated vast domestic inequality and increasing foreign intervention; and it emerged during the 1890s and 1910s, as America engaged in rapid territorial expansion, gobbling up Hawaii, Guam, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, the Panama Canal Zone, and various other small islands in the Pacific.

This anti-interventionist tradition again emerged during World War One, being led by various pacifist and socialist organizations who opposed the American government’s ongoing crackdowns on political and civil liberties. Thousands were jailed during this period, including famous socialist organizer Eugene Debs, who described America’s anti-democratic activity and foreign interventions quite bluntly: “They tell us that we live in a great free republic; that our institutions are democratic; that we are a free and self-governing people. That is too much, even for a joke. … Wars throughout history have been waged for conquest and plunder… And that is war in a nutshell. The master class has always declared the wars; the subject class has always fought the battles.”

War, beyond just being a racket, is now a fundamental part of our political economy.

As America emerged further into the 20th century, now having conquered various territories and peoples, the anti-interventionists found themselves trying to halt a forward march which seemed almost inexorable. While isolationist sentiment grew during this period, the birth of fascism and Soviet totalitarianism abroad forced many Americans to come to terms with what non-interventionist restraint—or even isolationism—would look like in a world littered with authoritarianism and violence.

The Great Depression and then World War Two eventually forced America’s hand and subsequently led to the undermining of Jeffersonian foreign policy. In the new world of the 20th century, restraint and non-interventionism could not survive the interwar period or the post-WW2 order. Fascism had to be defeated; genocides abroad could not be ignored; and entire regions of the world had to be reoriented and re-developed following intense conflict. Government, and especially the American one, could not be limited or restrained in its approach to the world. Following 1945, the world was now entirely different, shaped by new paradigms, new rules, and new assumptions about the role of American foreign policymaking.

The Incremental Return

Jeffersonian restraint had some resurgences throughout the latter half of the 20th century. Its climax emerged largely during the anti-war movement, as millions of Americans came together to oppose our country’s proxy wars in Indochina. But this movement, for all its publicity and moxie, eventually caved in on itself as domestic pressures and elite domination of foreign policy rendered its motors inactive. Despite bouts of domestic protest and opposition, America from 1945 to now has repeatedly engaged in wars and operations which have directly expanded our commitments and wars abroad.

Countless coups, civil wars, assassinations, rigged elections, and other covert operations have been launched by our intelligence services and militaries. Millions have died as a result of our conflicts, with Vietnam and Iraq serving as the worst examples of overreach. And much like the British before us, America since 1945 has found itself leading a global order which requires more and more resources. Trillions have been spent on these interventions, and all while domestically, American institutions and democratic strength have continued to decline.

American overreach has led to hundreds of military bases abroad, an increasingly bloated military budget, increased surveillance, and a military-industrial complex which is one of the most powerful lobbies in the country. War, beyond just being a racket, is now a fundamental part of our political economy. Both humanitarian interventionism and neoconservative logic have both found themselves being drained and supplanted by the harsh reality of graft and cash. Imperial power and its profitability have now replaced any notion of political principle, and as this has occurred, America has finally reached the point where its external decline is indeed beginning to boomerang.

Many Americans have noticed these conditions, and as decline has continued to be represented by both political and economic inequality, Jeffersonian traditions have indeed begun to emerge. Especially following our escapades into the Middle East, many engaged foreign policy activists and elites have come to view restraint and non-intervention not as a weakness, but as a possible avenue for strength. In a global order increasingly defined by climatic shocks and shortages, resources are going to become harder to come by, and as America comes to terms with this crisis, more corrections will likely be geared toward these emerging realities.

Various businesspeople, academics, congresspeople, and policy wonks have indeed come to recognize this, and instead of trying to repeatedly smash the imperial button—as we see currently in Venezuela—they are simply trying to fight for a foreign policy that finally departs from the post-1945 order. Within both parties, whether it’s opposition to America’s support of Israel, more aid for Ukraine, or even just the Trump administration’s regional actions against Venezuela and Greenland, many figures have come to broadly oppose intervention and entanglement.

Restraint, no longer an albatross, is now a rallying cry among an emerging segment of our political and foreign policy elite. Partially tied to class and partially tied to ideology, these emerging neo-Jeffersonians are indeed gaining steam, and as our nation’s imperial ambition only continues to run out of steam, it is increasingly likely that our political system will have to eventually come to terms with the new world we find ourselves in.

Empire Comes Home

The Neo-Jeffersonians are a result rather than a precursory warning. Unlike the restrainers of the past, we have now lived through imperial overreach and its effects; we have seen firsthand, much like Jefferson and his ilk did with the British, how foreign entanglements and imperial ambition could harm domestic rights and democratic accountability. Since 2000, America’s political system has been rocked by a series of political crises which have harmed both our civil liberties and our overall ranking as a democratic state.

Freedom of the press, freedom of speech, academic freedom, the right to privacy, and freedom from unwarranted search and seizure have all been increasingly weakened by both the war on terror and growing illiberalism. Colleges and media companies are being extorted, as are the law firms and independent agencies which do not follow the President’s direct wishes. The same logic has been applied to immigrants and foreign students who speak out against the administration, with some being disappeared for months without any right to trial.

Economically, monopoly capitalism and graft now dominate our system. Wealth and income inequality are at their highest in well over a century, as is cronyism and the increasing use of the state to benefit private actors, both foreign and domestic. Budgetary deficits, many of which are tied to foreign commitments and expanded defense procurements, have become more constraining. Wages are broadly stagnant, inflation is still rather high, and price gouging has become more common. Small and medium-sized businesses are struggling, as are young workers who now find themselves graduating into an economy where hiring rates are low, AI is disruptive, and assistance is scant.

Put these dual crises together and neo-Jeffersonianism’s purpose becomes much clearer. Rather than an homage, modern day Jeffersonians are attempting to build a new paradigm for American foreign policy, one in which lessons will be learned from the failures of our unipolar moment. In their minds, no longer can domestic freedoms and industrial competitiveness be sacrificed for imperial competition with China, nor can foreign alliances and proxy conflicts come to define our nation’s overarching goals abroad. Fundamentally, it is a movement which clamors for restraint, realism, and strategic minimalism abroad, viewing foreign commitments and conflicts as burdens rather than opportunities.

From its inception, Jeffersonianism, beyond the mere thoughts or criticisms of just one man, was a regional class project, designed by elite planters and shaped by a vehement reaction against British colonial overreach. In essence, it was an attempt to construct a new paradigm where state power was limited, agriculture was king, expansion was fundamental, and foreign relations were solved through “peaceable coercion[s].”

George Washington emerged from this milieu and quite famously gave a speech where he warned of entangling alliances and the threats of partisanship. Once in office, Jefferson also grew to adopt Washington’s line, especially as his once-admired France became plagued by Napoleon Bonaparte’s despotism. President after president came to adopt these Jeffersonian class principles in stride, and as America emerged into the 1810s and 1820s, alliances were largely avoided in favor of expansion and internal improvements.

As Jeffersonianism came to be interpreted by new generations of elites and political actors, however, mutations began to occur. Domestically, the growing desire for western expansion and yeoman farming became increasingly bogged down by a growing divide between America’s sectional economies. Northern farmers viewed Jeffersonianism’s promise as being anti-slavery and pro-free labor; Southerners viewed slavery and the protection of their property as being a fundamental purpose of government. Soon, Jeffersonianism’s promise of tight-knit rural communities became increasingly impossible as both sectional conflict and growing industrialization came to define 19th-century development.

Concurrently, on the foreign front, Jeffersonianism’s aversion to imperial war and foreign entanglement remained quite present and also rather pertinent as America continued to expand westward. Anti-war sentiment first emerged as America’s conquest of the west brought war with both Mexico and various Native American tribes. It was during the buildup to these contentious decades and conflicts where John Quincy Adams famously stated that “But she [America] goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.”

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, these Jeffersonian reactions repeatedly emerged during moments of intense polarization and imperial conquest. It emerged during our war with Mexico; it emerged as the Gilded Age generated vast domestic inequality and increasing foreign intervention; and it emerged during the 1890s and 1910s, as America engaged in rapid territorial expansion, gobbling up Hawaii, Guam, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, the Panama Canal Zone, and various other small islands in the Pacific.

This anti-interventionist tradition again emerged during World War One, being led by various pacifist and socialist organizations who opposed the American government’s ongoing crackdowns on political and civil liberties. Thousands were jailed during this period, including famous socialist organizer Eugene Debs, who described America’s anti-democratic activity and foreign interventions quite bluntly: “They tell us that we live in a great free republic; that our institutions are democratic; that we are a free and self-governing people. That is too much, even for a joke. … Wars throughout history have been waged for conquest and plunder… And that is war in a nutshell. The master class has always declared the wars; the subject class has always fought the battles.”

As America emerged further into the 20th century, now having conquered various territories and peoples, the anti-interventionists found themselves trying to halt a forward march which seemed almost inexorable. While

isolationist sentiment grew during this period, the birth of fascism and Soviet totalitarianism abroad forced many Americans to come to terms with what non-interventionist restraint—or even isolationism—would look like in a world littered with authoritarianism and violence.

The Great Depression and then World War Two eventually forced America’s hand and subsequently led to the undermining of Jeffersonian foreign policy. In the new world of the 20th century, restraint and non-interventionism could not survive the interwar period or the post-WW2 order. Fascism had to be defeated; genocides abroad could not be ignored; and entire regions of the world had to be reoriented and re-developed following intense conflict. Government, and especially the American one, could not be limited or restrained in its approach to the world. Following 1945, the world was now entirely different, shaped by new paradigms, new rules, and new assumptions about the role of American foreign policymaking.

The Incremental Return

Jeffersonian restraint had some resurgences throughout the latter half of the 20th century. Its climax emerged largely during the anti-war movement, as millions of Americans came together to oppose our country’s proxy wars in Indochina. But this movement, for all its publicity and moxie, eventually caved in on itself as domestic pressures and elite domination of foreign policy rendered its motors inactive. Despite bouts of domestic protest and opposition, America from 1945 to now has repeatedly engaged in wars and operations which have directly expanded our commitments and wars abroad.

Countless coups, civil wars, assassinations, rigged elections, and other covert operations have been launched by our intelligence services and militaries. Millions have died as a result of our conflicts, with Vietnam and Iraq serving as the worst examples of overreach. And much like the British before us, America since 1945 has found itself leading a global order which requires more and more resources. Trillions have been spent on these interventions, and all while domestically, American institutions and democratic strength have continued to decline.

American overreach has led to hundreds of military bases abroad, an increasingly bloated military budget, increased surveillance, and a military-industrial complex which is one of the most powerful lobbies in the country. War, beyond just being a racket, is now a fundamental part of our political economy. Both humanitarian interventionism and neoconservative logic have both found themselves being drained and supplanted by the harsh reality of graft and cash. Imperial power and its profitability have now replaced any notion of political principle, and as this has occurred, America has finally reached the point where its external decline is indeed beginning to boomerang.

Many Americans have noticed these conditions, and as decline has continued to be represented by both political and economic inequality, Jeffersonian traditions have indeed begun to emerge. Especially following our escapades into the Middle East, many engaged foreign policy activists and elites have come to view restraint and non-intervention not as a weakness, but as a possible avenue for strength. In a global order increasingly defined by climatic shocks and shortages, resources are going to become harder to come by, and as America comes to terms with this crisis, more corrections will likely be geared toward these emerging realities.

Various businesspeople, academics, congresspeople, and policy wonks have indeed come to recognize this, and instead of trying to repeatedly smash the imperial button—as we see currently in Venezuela—they are simply trying to fight for a foreign policy that finally departs from the post-1945 order. Within both parties, whether it’s opposition to America’s support of Israel, more aid for Ukraine, or even just the Trump administration’s regional actions against Venezuela and Greenland, many figures have come to broadly oppose intervention and entanglement.

Restraint, no longer an albatross, is now a rallying cry among an emerging segment of our political and foreign policy elite. Partially tied to class and partially tied to ideology, these emerging neo-Jeffersonians are indeed gaining steam, and as our nation’s imperial ambition only continues to run out of steam, it is increasingly likely that our political system will have to eventually come to terms with the new world we find ourselves in.

Empire Comes Home

The Neo-Jeffersonians are a result rather than a precursory warning. Unlike the restrainers of the past, we have now lived through imperial overreach and its effects; we have seen firsthand, much like Jefferson and his ilk did with the British, how foreign entanglements and imperial ambition could harm domestic rights and democratic accountability. Since 2000, America’s political system has been rocked by a series of political crises which have harmed both our civil liberties and our overall ranking as a democratic state.

Freedom of the press, freedom of speech, academic freedom, the right to privacy, and freedom from unwarranted search and seizure have all been increasingly weakened by both the war on terror and growing illiberalism. Colleges and media companies are being extorted, as are the law firms and independent agencies which do not follow the President’s direct wishes. The same logic has been applied to immigrants and foreign students who speak out against the administration, with some being disappeared for months without any right to trial.

Economically, monopoly capitalism and graft now dominate our system. Wealth and income inequality are at their highest in well over a century, as is cronyism and the increasing use of the state to benefit private actors, both foreign and domestic. Budgetary deficits, many of which are tied to foreign commitments and expanded defense procurements, have become more constraining. Wages are broadly stagnant, inflation is still rather high, and price gouging has become more common. Small and medium-sized businesses are struggling, as are young workers who now find themselves graduating into an economy where hiring rates are low, AI is disruptive, and assistance is scant.

Put these dual crises together and neo-Jeffersonianism’s purpose becomes much clearer. Rather than an homage, modern day Jeffersonians are attempting to build a new paradigm for American foreign policy, one in which lessons will be learned from the failures of our unipolar moment. In their minds, no longer can domestic freedoms and industrial competitiveness be sacrificed for imperial competition with China, nor can foreign alliances and proxy conflicts come to define our nation’s overarching goals abroad. Fundamentally, it is a movement which clamors for restraint, realism, and strategic minimalism abroad, viewing foreign commitments and conflicts as burdens rather than opportunities.

Various groups, from both the left and right, now fear overreach and domestic illiberalism more than the power of China and Russia. Questions over our commitments abroad have become common, with Europe often receiving much of this ire and criticism. Foreign allies are

now expected to pick up slack in both military preparedness and procurement. Largely, it is an environment where multipolarity, rather than being viewed as an encroaching threat, is now viewed as a fact of global affairs that must be reconciled with, and this truly is a shift for DC.

Domestically, while varied, this realist reaction has called for an interest-first agenda focused on improving internal political-economic problems. Green industrialization, targeted industrial policy, wealth redistribution, expanded healthcare access, a cutting of the military budget, and infrastructural development are all examples of what has been presented as worth pursuing. Political freedoms have also been highlighted as something in need of protection, with many attempting to carve an agenda which both attacks the national security-military apparatus while not undermining civil service independence or civil liberties.

It is ultimately an ideological project which has energy and promise, both moxie and the ability to appeal to growing discontent among the American people. But much like previous Jeffersonians, it is not without its own shortcomings and contradictions.

Realism’s self-interest is often vague and shaped by partisan leaning. While libertarians and progressives may agree on eschewing war and international entanglement, they are very likely going to disagree on what must be done domestically to strengthen liberty and renewal. Concurrently, many conservative figures, while opposing military intervention, have had no problem interfering in regional and global affairs, such as in recent European and South American elections. Many of these same figures have also had no quarrels with the Trump administration’s ongoing attacks against the administrative state and civil liberties. While largely united on external affairs, these various political strands will inevitably find themselves disagreeing harshly over what our country’s domestic politics and interests should be oriented around. This will cause conflict, and no amount of anti-interventionism will paper over this reality.

Realism’s restraint bent is also going to face mountains of criticism as global affairs become more unruly and conflict-driven. As we see currently with the genocides in Gaza and Sudan, or with Russia’s war against Ukraine, symbolic leading by example can only take you so far. While reducing aid or engagement with global perpetrators may be a good first step, where would these actions go from here? Would America then work with international organizations to help oppose these countries through sanctions or embargoes? Would this increased international engagement be considered an entanglement or a threat against our liberty? Moreover, how would our country’s shining example even help to stop atrocities without any kind of enforcement mechanism?

To claim to support global democracy and liberty but then only back it up with symbolism is great in principle. But in reality, this worldview is bound to run headfirst against harsh realities which will demand much and provide little. The American population, while opposing intervention, will not stand idly by if global atrocities are committed and our country chooses to do nothing. They will not accept a government which, by trying to eschew the last 80 years of globalist development, inadvertently builds a new foreign policy which is reckless, isolationist, and antiquated. Change is being demanded, but the likelihood that this change will be led by a comprehensive neo-Jeffersonian movement without flaws or contradictions is highly unrealistic.

Why Less Can Be More

Jeffersonianism’s place within American politics has evolved countless times throughout our country’s history. Its foreign policy goals and views, while sometimes prominent, have instead often been sidelined as new conditions and conflicts demanded a far more interventionist and engaged America. Washington and Jefferson never could have predicted the rise of fascism or its ability to inflict such widespread destruction and killing. The founders and the framers never could have conceived of capitalism’s ability to rapidly industrialize and urbanize our society, nor did they have the clairvoyance to predict the emergence of a globalized world order where commerce, trade, diplomacy, and transportation would all be predicated on global engagement and interaction.

Isolationism and comprehensive American retrenchment are both unlikely in our globalized world, but what the neo-Jeffersonians have shown us is that the promises of less war and conflict are indeed possible. Americans are not clamoring for war with Venezuela, and many are taking growingly hostile stands against possible American intervention in Asia and the North Atlantic. Skepticism in Washington over foreign spending and alliances is also at its highest in well over 90 years, and the public’s demand for domestic renewal now triumphs any kind of commitment to international policing or intervention.

Put simply, after nearly 80 years of an American-led global order, American politics is finally coming around to the idea that conditions and policies will have to change within the foreign policy realm. Some will attempt to repackage interventionism to make it more palatable and popular; others will try to supercharge our country toward a new cold war with China; and many will likely just end up following which way the short-term foreign policy winds are blowing. But in the long term, domestic fatigue and broad insecurity will help to reduce the amount of political capital that these groups are afforded. Now more than ever, both restraint and non-interventionism have an incredible opportunity to reshape American foreign policy. And if anyone can do it successfully, it will likely be within the age-old tradition which is as American as apple pie.

To claim to support global democracy and liberty but then only back it up with symbolism is great in principle.

Various groups, from both the left and right, now fear overreach and domestic illiberalism more than the power of China and Russia. Questions over our commitments abroad have become common, with Europe often receiving much of this ire and criticism. Foreign allies are now expected to pick up slack in both military preparedness and procurement. Largely, it is an environment where multipolarity, rather than being viewed as an encroaching threat, is now viewed as a fact of global affairs that must be reconciled with, and this truly is a shift for DC.

Domestically, while varied, this realist reaction has called for an interest-first agenda focused on improving internal political-economic problems. Green industrialization, targeted industrial policy, wealth redistribution, expanded healthcare access, a cutting of the military budget, and infrastructural development are all examples of what has been presented as worth pursuing. Political freedoms have also been highlighted as something in need of protection, with many attempting to carve an agenda which both attacks the national security-military apparatus while not undermining civil service independence or civil liberties.

It is ultimately an ideological project which has energy and promise, both moxie and the ability to appeal to growing discontent among the American people. But much like previous Jeffersonians, it is not without its own shortcomings and contradictions.

Realism’s self-interest is often vague and shaped by partisan leaning. While libertarians and progressives may agree on eschewing war and international entanglement, they are very likely going to disagree on what must be done domestically to strengthen liberty and renewal. Concurrently, many conservative figures, while opposing military intervention, have had no problem interfering in regional and global affairs, such as in recent European and South American elections. Many of these same figures have also had no quarrels with the Trump administration’s ongoing attacks against the administrative state and civil liberties. While largely united on external affairs, these various political strands will inevitably find themselves disagreeing harshly over what our country’s domestic politics and interests should be oriented around. This will cause conflict, and no amount of anti-interventionism will paper over this reality.

Realism’s restraint bent is also going to face mountains of criticism as global affairs become more unruly and conflict-driven. As we see currently with the genocides in Gaza and Sudan, or with Russia’s war against Ukraine, symbolic leading by example can only take you so far. While reducing aid or engagement with global perpetrators may be a good first step, where would these actions go from here? Would America then work with international organizations to help oppose these countries through sanctions or embargoes? Would this increased international engagement be considered an entanglement or a threat against our liberty? Moreover, how would our country’s shining example even help to stop atrocities without any kind of enforcement mechanism?

To claim to support global democracy and liberty but then only back it up with symbolism is great in principle. But in reality, this worldview is bound to run headfirst against harsh realities which will demand much and provide little. The American population, while opposing intervention, will not stand idly by if global atrocities are committed and our country chooses to do nothing. They will not accept a government which, by trying to eschew the last 80 years of globalist development, inadvertently builds a new foreign policy which is reckless, isolationist, and antiquated. Change is being demanded, but the likelihood that this change will be led by a comprehensive neo-Jeffersonian movement without flaws or contradictions is highly unrealistic.

Why Less Can Be More

Jeffersonianism’s place within American politics has evolved countless times throughout our country’s history. Its foreign policy goals and views, while sometimes prominent, have instead often been sidelined as new conditions and conflicts demanded a far more interventionist and engaged America. Washington and Jefferson never could have predicted the rise of fascism or its ability to inflict such widespread destruction and killing. The founders and the framers never could have conceived of capitalism’s ability to rapidly industrialize and urbanize our society, nor did they have the clairvoyance to predict the emergence of a globalized world order where commerce, trade, diplomacy, and transportation would all be predicated on global engagement and interaction.

Isolationism and comprehensive American retrenchment are both unlikely in our globalized world, but what the neo-Jeffersonians have shown us is that the promises of less war and conflict are indeed possible. Americans are not clamoring for war with Venezuela, and many are taking growingly hostile stands against possible American intervention in Asia and the North Atlantic. Skepticism in Washington over foreign spending and alliances is also at its highest in well over 90 years, and the public’s demand for domestic renewal now triumphs any kind of commitment to international policing or intervention.

Put simply, after nearly 80 years of an American-led global order, American politics is finally coming around to the idea that conditions and policies will have to change within the foreign policy realm. Some will attempt to repackage interventionism to make it more palatable and popular; others will try to supercharge our country toward a new cold war with China; and many will likely just end up following which way the short-term foreign policy winds are blowing. But in the long term, domestic fatigue and broad insecurity will help to reduce the amount of political capital that these groups are afforded. Now more than ever, both restraint and non-interventionism have an incredible opportunity to reshape American foreign policy. And if anyone can do it successfully, it will likely be within the age-old tradition which is as American as apple pie.

Recommended

Is a Common European Identity Still Possible?

China’s Post-Ideological Strategy of Power

Inside the World’s Most Enduring Dictatorship

How the War in Ukraine Redefined Europe?

From Democratic Promise to Authoritarian Reality