Can a great power truly lead the world through moral vision rather than sheer force? This question has long defined American foreign policy. For many in diplomacy, development, and human rights, the answer once seemed clear: U.S. leadership meant advancing justice by building institutions, nurturing cooperation, and defending shared values. Yet this ideal, liberal internationalism, has always been in tension with Realpolitik, the pursuit of power by any means necessary. The realist impulse shaped nineteenth-century U.S. policy, where expansion and self-interest reigned. It never vanished. From Cold War proxy wars to post-9/11 interventions, American strategy has swung between the pull of ideals and the push of raw interests.

A turning point came with Woodrow Wilson, who envisioned America wielding influence as a moral force. The carnage of World War I, he argued, proved the bankruptcy of power politics. Lasting peace, he believed, must rest not on rival alliances but on law and shared values. His call for a League of Nations sought to institutionalize cooperation and justice over narrow ambition. As historian Arthur S. Link observed, “Wilson’s statesmanship was animated by a vision of a new international order based on law and morality, not power politics.”

Yet Wilson’s vision was riddled with contradiction. A staunch segregationist, he preached self-determination abroad but ignored colonial subjugation in Africa and Asia. At Versailles, he dismissed petitions from colonized peoples, including a young Ho Chi Minh, revealing the limits of his moral reach. As historian Erez Manela argues in The Wilsonian Moment, Wilson’s rhetoric inspired anti-colonial movements worldwide even as his own policies exposed American hypocrisy.

Still, Wilson’s ideas endured. The creation of the United Nations, NATO, and the Bretton Woods system reflected the belief that U.S. leadership was credible not when it served itself, but when it served something greater, the security and dignity of the international community. Today, that legacy is under strain. U.S. commitments to development, diplomacy, and cooperation have waned, replaced by a narrower “America First” posture that questions whether moral leadership still matters. Yet America’s greatest victories have rarely come from military might, but from building partnerships, turning rivals into allies, investing in development, and promoting human rights.

For all its flaws and double standards, from Vietnam to Iraq, and from backing dictators to tolerating abuses, the United States has remained, for many, a symbol of justice and freedom. Dissidents, reformers, and oppressed communities have long looked to Washington not for perfection, but for possibility. Its Constitution, civil rights legacy, and global advocacy for democracy, even inconsistently applied, made it a moral reference point for universal aspirations.

This paradox is Wilson’s enduring inheritance, a nation caught between power and principle. America has never fully lived up to the role of moral leader, yet the world still measures it against that ideal. That, in itself, speaks to the Wilsonian promise, that moral purpose, however imperfectly realized, remains essential to global order. The question is not whether values can guide foreign policy, but whether we still choose to let them. Indeed, the deeper question is not simply whether values can guide foreign policy at all, but whether any strategy can endure without justice at its core. The evidence suggests we can. From the U.S.-led coalition confronting Russia’s aggression in Ukraine to the life-saving reach of PEPFAR, America continues to prove that when it leads with values, it makes the world safer, freer, and more just.

The Moral Foundations of U.S. Leadership

Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points stood as one of the foundational documents of a new world order. When he unveiled them in 1918, Americans were stirred by his idealism, a vision of peace grounded in justice, transparency, and moral leadership. Progressives hailed his call for open diplomacy, disarmament, and moral cooperation as a turning point in U.S. foreign policy. As historian John Milton Cooper Jr. observed, Wilson’s rhetoric captured the nation’s desire to align moral principle with power, though it set expectations no peace treaty could meet. Yet enthusiasm soon gave way to skepticism. Henry Kissinger later argued that Wilson’s moral universalism “collided with the realities of power politics,” dividing Americans between idealism and pragmatism.

is a former USAID Foreign Service Officer, a UNESCO Policy Lab Expert, and a graduate instructor at NYU’s Center for Global Affairs, specializing in post-conflict development, human rights, and transitional justice.

At home, isolationists condemned the League of Nations as a threat to sovereignty. Historian Thomas A. Bailey noted that many in Congress saw it as a “trap that would shackle American independence,” while diplomatic historian George F. Kennan described public sentiment as leaning “toward withdrawal rather than crusade.” Across the Atlantic, European leaders admired Wilson’s vision but dismissed it as naïve. French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau mocked, “God himself was content with Ten Commandments, but Wilson insists on fourteen.” As Margaret MacMillan recounts in Paris 1919, Clemenceau and Lloyd George prioritized security and empire over Wilson’s universalist ideals.

Despite opposition, Wilson pressed on, believing that democracy, law, and multilateralism were not luxuries but necessities for peace. Yet in the end, the U.S. Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles, and America never joined the League of Nations. Though his plan failed, Wilson’s ideals endured. As historian Alan Brinkley observed, his internationalism collapsed at home but its moral legacy shaped American diplomacy throughout the twentieth century. Wilson’s ideas helped lay the intellectual and ethical foundations for later supranational institutions, from the United Nations to NATO, the European Union, and the African Union, all reflections of the enduring Wilsonian belief that democracy, law, and cooperation remain essential to global stability.

The notion of leading through moral legitimacy and principle became one of the United States’ greatest strategic assets, especially as it entered a bipolar world and competed with the Soviet Union for global influence and the hearts and minds of emerging nations. In the aftermath of World War II, the United States launched a series of initiatives to rebuild war-torn regions and stabilize the international order, efforts that advanced democracy, self-determination, and respect for human rights. Chief among these was the Marshall Plan, a sweeping economic recovery program announced by Secretary of State George C. Marshall in 1947. Through this initiative, the United States provided more than $13 billion in aid to Western European countries, not only to rebuild infrastructure and revive economies, but also to prevent the spread of communism by fostering prosperity and democratic stability. The plan reflected the enduring Wilsonian belief that peace depended on justice, cooperation, and shared economic security, principles that would come to define the postwar liberal order and anchor U.S. leadership in the twentieth century. The United States also leveraged this moral legitimacy as it confronted autocrats and totalitarian regimes around the world, establishing, just as Wilson had envisioned, the moral and political standards by which democracy, justice, and human rights would be judged in the modern era.

Along these lines, the United States maintained protocols in its foreign policy and development practice that reinforced these values. It established policies to restrict lending and development assistance to known human rights abusers, implemented sanctions against regimes responsible for atrocities, and required annual human rights reports through the Department of State to assess global conditions. Over time, additional mechanisms such as the Global Magnitsky Act, the Foreign Assistance Act, and U.S. participation in multilateral institutions like the World Bank, IMF, and UN Human Rights Council further embedded human rights considerations into economic and diplomatic decision-making. These frameworks reflected a continuing effort to align American power with moral purpose, echoing Wilson’s conviction that legitimacy in global affairs rests not merely on strength, but on principle.

In the end, the U.S. presidency came to be known as the leader of the free world precisely for embodying these Wilsonian ideals in both principle and practice. Over time, the office itself came to wield a unique form of moral power, one that positioned the president as a global broker for peace, a defender of democracy, and at times, the conscience of the international community. From Wilson to Obama, each administration carried forward some dimension of this moral legacy, using American power not only to defend national interests but to promote a vision of justice and human dignity. While far from perfect or wholly commendable, political agendas and shifting priorities often influenced how this moral legitimacy was exercised or ignored. Even so, this legacy materialized in the creation of institutions such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the Peace Corps, and an expanding framework for humanitarian intervention and global development assistance. The United States became not just a superpower, but a standard-bearer of moral responsibility, shaping a world order that sought to balance power with purpose.

Justice as Foreign Policy

The international organizations that have grown and expanded over the decades, such as NATO, the European Union, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), are not merely partnerships established to maintain or protect security. They are communities of nations committed to what might be called a shared gospel, united in common ideals of democracy, human rights, good governance, and economic prosperity. These shared norms and values have done more than strengthen alliances. They have cultivated a way of life and a new collective identity. Across borders, citizens increasingly recognize one another as participants in a common pursuit of something larger and greater than the nation-state: the enduring project of peace, dignity, and mutual progress.

At home, isolationists condemned the League of Nations as a threat to sovereignty. Historian Thomas A. Bailey noted that many in Congress saw it as a “trap that would shackle American independence,” while diplomatic historian George F. Kennan described public sentiment as leaning “toward withdrawal rather than crusade.” Across the Atlantic, European leaders admired Wilson’s vision but dismissed it as naïve. French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau mocked, “God himself was content with Ten Commandments, but Wilson insists on fourteen.” As Margaret MacMillan recounts in Paris 1919, Clemenceau and Lloyd George prioritized security and empire over Wilson’s universalist ideals.

Despite opposition, Wilson pressed on, believing that democracy, law, and multilateralism were not luxuries but necessities for peace. Yet in the end, the U.S. Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles, and America never joined the League of Nations. Though his plan failed, Wilson’s ideals endured. As historian Alan Brinkley observed, his internationalism collapsed at home but its moral legacy shaped American diplomacy throughout the twentieth century. Wilson’s ideas helped lay the intellectual and ethical foundations for later supranational institutions, from the United Nations to NATO, the European Union, and the African Union, all reflections of the enduring Wilsonian belief that democracy, law, and cooperation remain essential to global stability.

The notion of leading through moral legitimacy and principle became one of the United States’ greatest strategic assets, especially as it entered a bipolar world and competed with the Soviet Union for global influence and the hearts and minds of emerging nations. In the aftermath of World War II, the United States launched a series of initiatives to rebuild war-torn regions and stabilize the international order, efforts that advanced democracy, self-determination, and respect for human rights. Chief among these was the Marshall Plan, a sweeping economic recovery program announced by Secretary of State George C. Marshall in 1947. Through this initiative, the United States provided more than $13 billion in aid to Western European countries, not only to rebuild infrastructure and revive economies, but also to prevent the spread of communism by fostering prosperity and democratic stability. The plan reflected the enduring Wilsonian belief that peace depended on justice, cooperation, and shared economic security, principles that would come to define the postwar liberal order and anchor U.S. leadership in the twentieth century. The United States also leveraged this moral legitimacy as it confronted autocrats and totalitarian regimes around the world, establishing, just as Wilson had envisioned, the moral and political standards by which democracy, justice, and human rights would be judged in the modern era.

Along these lines, the United States maintained protocols in its foreign policy and development practice that reinforced these values. It established policies to restrict lending and development assistance to known human rights abusers, implemented sanctions against regimes responsible for atrocities, and required annual human rights reports through the Department of State to assess global conditions. Over time, additional mechanisms such as the Global Magnitsky Act, the Foreign Assistance Act, and U.S. participation in multilateral institutions like the World Bank, IMF, and UN Human Rights Council further embedded human rights considerations into economic and diplomatic decision-making. These frameworks reflected a continuing effort to align American power with moral purpose, echoing Wilson’s conviction that legitimacy in global affairs rests not merely on strength, but on principle.

In the end, the U.S. presidency came to be known as the leader of the free world precisely for embodying these Wilsonian ideals in both principle and practice. Over time, the office itself came to wield a unique form of moral power, one that positioned the president as a global broker for peace, a defender of democracy, and at times, the conscience of the international community. From Wilson to Obama, each administration carried forward some dimension of this moral legacy, using American power not only to defend national interests but to promote a vision of justice and human dignity. While far from perfect or wholly commendable, political agendas and shifting priorities often influenced how this moral legitimacy was exercised or ignored. Even so, this legacy materialized in the creation of institutions such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the Peace Corps, and an expanding framework for humanitarian intervention and global development assistance. The United States became not just a superpower, but a standard-bearer of moral responsibility, shaping a world order that sought to balance power with purpose.

Justice as Foreign Policy

The international organizations that have grown and expanded over the decades, such as NATO, the European Union, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), are not merely partnerships established to maintain or protect security. They are communities of nations committed to what might be called a shared gospel, united in common ideals of democracy, human rights, good governance, and economic prosperity. These shared norms and values have done more than strengthen alliances. They have cultivated a way of life and a new collective identity. Across borders, citizens increasingly recognize one another as participants in a common pursuit of something larger and greater than the nation-state: the enduring project of peace, dignity, and mutual progress.

One of the key buzzwords I encountered while working in the Balkans was the notion of Euro-Atlantic integration, a process through which states of the former Yugoslavia and Soviet Union were drawn into the broader Euro-Atlantic space of values and institutions. At the end of the Cold War, this integration represented both a political and moral reward for countries that prioritized democracy, human rights, and free-market economies. It symbolized entry into a community defined not merely by treaties and defense pacts, but by a shared belief in liberal democracy as the cornerstone of peace and prosperity. And, for the most part, this has proven true. As the democratic peace theory suggests, democratic states bound by shared values and mutual interests are far less likely to go to war with one another, reinforcing the notion that cooperation and common ideals remain the surest safeguards of lasting peace.

Maintaining these values, and ensuring that those who belong to these communities remain genuinely committed to them, is essential to their strength and credibility. This is precisely why membership in NATO and the European Union involves such a rigorous and often prolonged process. Every member must demonstrate a true dedication to the shared principles of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. When these values erode, alliances begin to fracture. For instance, Serbia’s ongoing interest in joining NATO illustrates this tension. While the country has expressed aspirations toward Euro-Atlantic integration, its continued political and military closeness with Russia raises questions about its alignment with NATO’s core democratic and security principles. Similarly, within the European Union, countries such as Poland and Hungary have faced growing criticism and even formal rebuke for democratic backsliding, politicized judiciaries, and restrictions on media freedom. These challenges have strained their relationships with Brussels, highlighting how the erosion of shared values can undermine not only trust but the very cohesion of the alliances themselves. Upholding these principles is therefore not a symbolic exercise. It is the moral and political glue that keeps the liberal international order intact.

Humanitarian intervention embodies one of international relations’ enduring paradoxes, the clash between moral responsibility and political self-interest. One of the key ideas that evolved from Wilsonian philosophy, it sought to elevate human rights above the sovereignty of states and to enshrine moral duty as a cornerstone of global order. After World War II, interventions justified on humanitarian grounds, from Bosnia and Herzegovina to Libya, revealed both the promise and the peril of this idealism. While intended to prevent atrocities, such actions often exposed deep contradictions over legitimacy and selectivity. Who decides when to intervene, and whose suffering merits protection?

The later emergence of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine reflects a modern extension of Wilsonian ideals, asserting that the international community has a moral duty to act when states fail to protect their citizens. Yet even with R2P in effect, the practice of humanitarian intervention continues to test the boundaries of the U.N. Charter’s commitment to state sovereignty and non-interference, and remains constrained by realpolitik, where doing the right thing often clashes with national interest. The Clinton administration’s reluctance to act during the 1994 Rwandan genocide, shaped by the loss of U.S. soldiers in Somalia, underscored this tension. Similarly, the United States’ continued support for Israel amid the bombardment of Gaza, and Russia’s repeated vetoes blocking U.N. action in Syria, reveal how political calculations still determine when, and for whom, humanity intervenes. This uneven application reflects an enduring hierarchy of human suffering, where some lives are deemed more “intervenable” than others.

Taken together, Rwanda represents the failure to act when intervention was morally essential, Gaza reflects the tendency to shield allies despite grave humanitarian costs, and Syria illustrates how geopolitical rivalry can paralyze collective action even as atrocities mount. And as I write this, with genocide again unfolding in Darfur, the international community remains largely silent, proof that moral resolve continues to yield to political convenience. Until moral responsibility outweighs political expedience, the promise of Wilsonian idealism will remain just that, a promise unfulfilled.

The international legal mechanisms for justice and human rights, anchored in the principles of international law and embodied by institutions such as the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, UN treaty bodies, the International Criminal Court (ICC), and the International Court of Justice (ICJ), are not merely procedural forums. They represent a noble pursuit to uphold accountability and preserve peace and order across the globe. These institutions lay the foundation for a moral order and civility within the international community.

When accountability becomes selective, justice devolves into political theater.

In 2025, they are more vital than ever as the world once again confronts war and war crimes across the globe. Without them, where and how would we preserve our shared sense of humanity? Though often entangled in politics, international justice mechanisms remain essential for holding both states and non-state actors accountable. History offers powerful reminders of their necessity. Without the Nuremberg Trials, countless Nazi perpetrators would have escaped justice for committing some of humanity’s darkest crimes. Without the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), many victims of genocide in Bosnia and Herzegovina would never have known the fate of their children, spouses, siblings, or parents.

American leadership depends on defending, not bypassing, these institutions, for they embody the very ideals of justice, dignity, and the rule of law that the United States claims to champion. The U.S. played a central role in shaping this global architecture of accountability, from leading the Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials to supporting the establishment of the ICTY and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), both precursors to the International Criminal Court (ICC). While Washington has yet to fully embrace ICC membership, its historical commitment to justice helped lay the groundwork for the Court’s creation under the Rome Statute in 2002.

However, in recent years, the United States has backtracked on many of these efforts, at times even undermining the very institutions it helped build. By rejecting the authority of international courts, sanctioning ICC officials, and applying double standards in accountability, America risks eroding the credibility of the global justice system it once championed. After all, why should perpetrators of war crimes in Sudan, such as Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemedti) and other Rapid Support Forces commanders accused of orchestrating atrocities in Darfur and across Sudan, be held accountable if U.S. allies like Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and senior Israeli defense officials are not? When accountability becomes selective, justice devolves into political theater. Justice that is uneven or lopsided is not justice at all. Delegitimizing these institutions weakens the very international order that Wilsonians sought to sustain, an order rooted in law, moral leadership, and shared responsibility. To preserve that order, nations must recommit to universal principles of justice and accountability, ensuring that international law applies not only to the weak, but to the powerful as well. That is global primacy, not selective application.

The Crisis of Wilsonianism

After the Cold War, the United States embarked on what became known as the freedom agenda, a sweeping vision to promote democracy, free markets, and human rights as the cornerstones of a stable world order. Rooted in the belief that democratic governance would naturally lead to peace and prosperity, it reflected America’s conviction that its model could and should be replicated globally. In theory, it was a moral mission; in practice, it often blurred the line between idealism and interventionism. In the wake of 9/11, this agenda took on a militant edge, manifesting most visibly in Iraq and Afghanistan. The effort to implant democracy in societies fractured by conflict, colonial legacies, and sectarian divides proved both ill-timed and ill-prepared. What followed was not the triumph of liberty, but a sobering lesson in overreach.

Washington’s vision became clouded by arrogance and moral hegemony, the assumption that democracy could be imposed from above and would automatically take hold once authoritarian regimes were removed. The U.S. congressional reports that followed the Iraq invasion exposed these failures in stark detail: faulty intelligence, poor post-war planning, and a deep misunderstanding of Iraq’s political and social fabric. Toppling Saddam Hussein did not bring democracy; it unleashed chaos, sectarianism, and widespread disillusionment with the very ideals America sought to promote.

The tragic return of the Taliban in Afghanistan stands as an equally harsh reminder of what happens when democracy is imposed rather than cultivated. After two decades of war, nation-building, and promises of freedom, Afghanistan reverted to authoritarian rule almost overnight, revealing the fragility of institutions built on foreign scaffolding rather than local legitimacy.

After all, democracy is not an exportable commodity but a lived conviction, one that can only endure when people themselves desire it, nurture it, and fight for it. This truth is evident in the Arab Spring, when citizens across the Middle East and North Africa rose up to demand dignity, justice, and reform. Their courage proved that the yearning for freedom must come from within, yet their struggles also showed how fragile democracy remains when hope outpaces institutions. This tension is often at the heart of criticism directed at U.S. democracy and governance programs. Skeptics argue that initiatives funded by USAID, the State Department’s DRL Bureau, and other Western donors can cross the line into social engineering or political interference. These critiques gain traction in places where local histories are marked by colonialism, foreign interventions, or Cold War proxy battles. But the deeper truth is that no external actor can impose democracy where people do not want it, and no external actor can extinguish it where they do.

This lesson is deeply germane to the American experience, born of struggle, dissent, and a collective insistence on self-governance. Even with a Constitution in place, women’s rights and civil rights for all were not granted easily; they had to be fought for, won through persistence, protest, and sacrifice. The enduring truth is clear. Democracy cannot be delivered by drone or decree. It must be demanded, defended, and defined by the people themselves.

This question lies at the heart of America’s modern identity crisis. The United States has long defined its leadership through the language of freedom, human rights, and democracy, yet its credibility gap has widened as it grapples with internal divisions and authoritarian impulses that mirror the very forces it claims to oppose abroad. The January 6th insurrection, rising corruption, deep racial and partisan polarization, and persistent voter suppression have exposed cracks in America’s democratic foundation. These are not isolated issues but signs of institutional fragility and moral drift. The attack on the Capitol was more than an assault on a building. It was an assault on the peaceful transfer of power, revealing how disinformation, extremism, and populist rage can erode democracy from within. Even more alarming, efforts to pardon or glorify January 6th insurrectionists further normalize political violence and contempt for democratic accountability. When acts of sedition are recast as patriotism, the rule of law is not merely weakened; it is inverted.

Meanwhile, the influence of money in politics, gerrymandering, and restrictive voting laws has further undermined public trust, as once-neutral institutions like the courts, press, and electoral system have become partisan battlegrounds. This climate of division and fear has created fertile ground for authoritarian tendencies to take root, replacing dialogue with resentment and democratic compromise with contempt.

This erosion of integrity underscores the danger of performative moralism, a foreign policy that preaches justice abroad while failing to uphold it at home. When moral rhetoric is not matched by institutional consistency, it becomes hollow, a performance rather than a principle. The defunding of USAID and the U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP), the downgrading of the State Department’s Human Rights Report, and politically motivated claims of genocide, such as those leveled against South Africa while ignoring actual genocides elsewhere, only deepen this hypocrisy. When ideals are wielded for convenience, values become slogans, and leadership turns into theater. To reclaim credibility, America must restore institutional integrity and live by the same moral standards it demands of others, leading not by proclamation, but through principled example.

Predictably, this double standard and erosion of moral credibility have not gone unnoticed. Russia, China, and Iran have emerged as the loudest critics of Western hypocrisy, exploiting America’s contradictions to expand their global influence. They cast the West’s promotion of democracy and human rights as selective and self-serving, and too often, that narrative resonates. Having served in a country like Nicaragua, I witnessed firsthand how governments isolated by U.S. and EU sanctions sought political and economic refuge through alliances with Moscow and Beijing. For illiberal regimes, such partnerships provide both survival and legitimacy, filling the moral vacuum left by Western inconsistency.

One of the key buzzwords I encountered while working in the Balkans was the notion of Euro-Atlantic integration, a process through which states of the former Yugoslavia and Soviet Union were drawn into the broader Euro-Atlantic space of values and institutions. At the end of the Cold War, this integration represented both a political and moral reward for countries that prioritized democracy, human rights, and free-market economies. It symbolized entry into a community defined not merely by treaties and defense pacts, but by a shared belief in liberal democracy as the cornerstone of peace and prosperity. And, for the most part, this has proven true. As the democratic peace theory suggests, democratic states bound by shared values and mutual interests are far less likely to go to war with one another, reinforcing the notion that cooperation and common ideals remain the surest safeguards of lasting peace.

Maintaining these values, and ensuring that those who belong to these communities remain genuinely committed to them, is essential to their strength and credibility. This is precisely why membership in NATO and the European Union involves such a rigorous and often prolonged process. Every member must demonstrate a true dedication to the shared principles of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. When these values erode, alliances begin to fracture. For instance, Serbia’s ongoing interest in joining NATO illustrates this tension. While the country has expressed aspirations toward Euro-Atlantic integration, its continued political and military closeness with Russia raises questions about its alignment with NATO’s core democratic and security principles. Similarly, within the European Union, countries such as Poland and Hungary have faced growing criticism and even formal rebuke for democratic backsliding, politicized judiciaries, and restrictions on media freedom. These challenges have strained their relationships with Brussels, highlighting how the erosion of shared values can undermine not only trust but the very cohesion of the alliances themselves. Upholding these principles is therefore not a symbolic exercise. It is the moral and political glue that keeps the liberal international order intact.

Humanitarian intervention embodies one of international relations’ enduring paradoxes, the clash between moral responsibility and political self-interest. One of the key ideas that evolved from Wilsonian philosophy, it sought to elevate human rights above the sovereignty of states and to enshrine moral duty as a cornerstone of global order. After World War II, interventions justified on humanitarian grounds, from Bosnia and Herzegovina to Libya, revealed both the promise and the peril of this idealism. While intended to prevent atrocities, such actions often exposed deep contradictions over legitimacy and selectivity. Who decides when to intervene, and whose suffering merits protection?

The later emergence of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine reflects a modern extension of Wilsonian ideals, asserting that the international community has a moral duty to act when states fail to protect their citizens. Yet even with R2P in effect, the practice of humanitarian intervention continues to test the boundaries of the U.N. Charter’s commitment to state sovereignty and non-interference, and remains constrained by realpolitik, where doing the right thing often clashes with national interest. The Clinton administration’s reluctance to act during the 1994 Rwandan genocide, shaped by the loss of U.S. soldiers in Somalia, underscored this tension. Similarly, the United States’ continued support for Israel amid the bombardment of Gaza, and Russia’s repeated vetoes blocking U.N. action in Syria, reveal how political calculations still determine when, and for whom, humanity intervenes. This uneven application reflects an enduring hierarchy of human suffering, where some lives are deemed more “intervenable” than others.

Taken together, Rwanda represents the failure to act when intervention was morally essential, Gaza reflects the tendency to shield allies despite grave humanitarian costs, and Syria illustrates how geopolitical rivalry can paralyze collective action even as atrocities mount. And as I write this, with genocide again unfolding in Darfur, the international community remains largely silent, proof that moral resolve continues to yield to political convenience. Until moral responsibility outweighs political expedience, the promise of Wilsonian idealism will remain just that, a promise unfulfilled.

The international legal mechanisms for justice and human rights, anchored in the principles of international law and embodied by institutions such as the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, UN treaty bodies, the International Criminal Court (ICC), and the International Court of Justice (ICJ), are not merely procedural forums. They represent a noble pursuit to uphold accountability and preserve peace and order across the globe. These institutions lay the foundation for a moral order and civility within the international community.

America’s challenge is no longer simply to outspend or outmaneuver its rivals; it is to reclaim the moral credibility that once made its leadership aspirational.

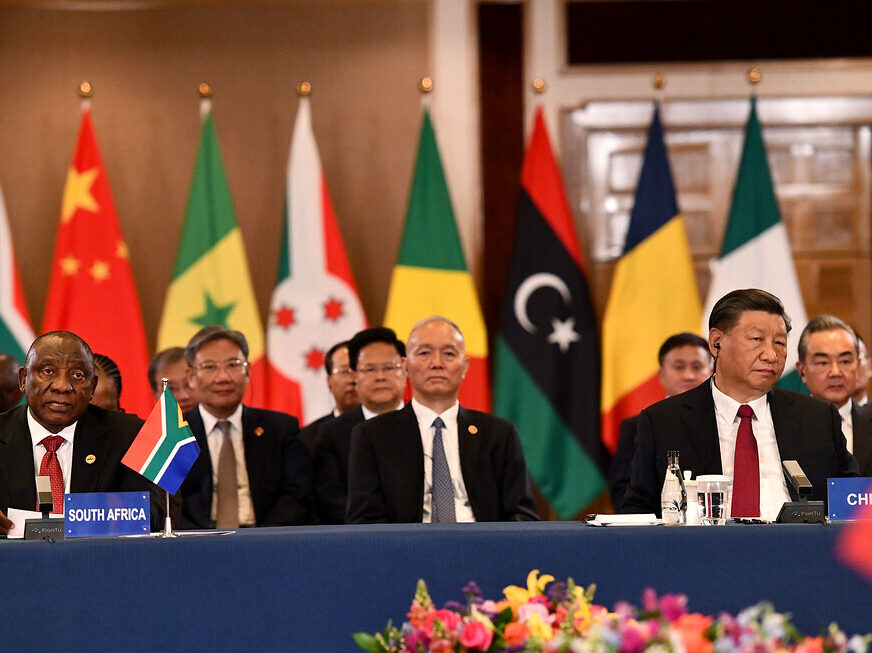

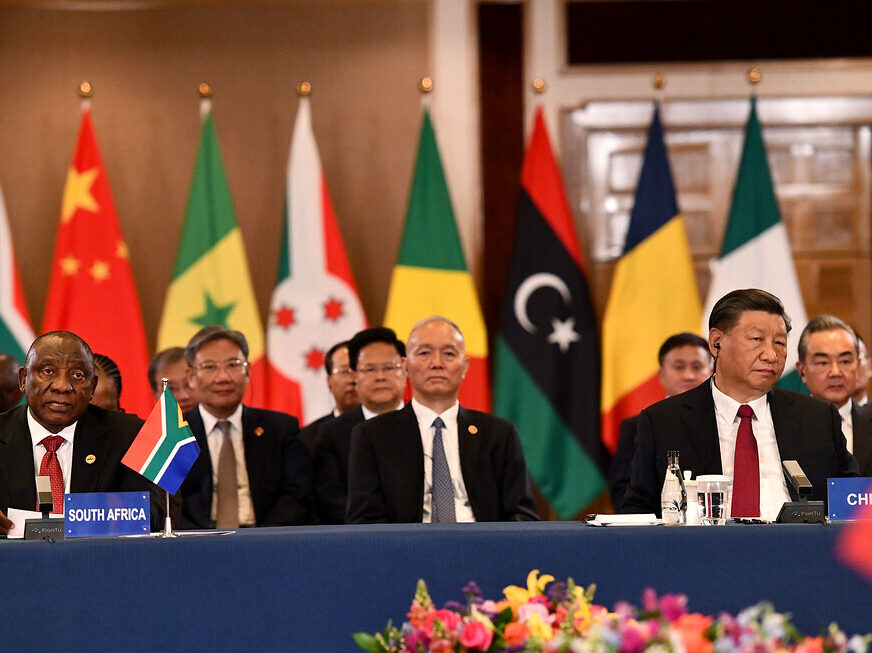

China, in particular, has seized this opening through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which now involves over 150 countries, representing nearly two-thirds of the world’s population and about 40 percent of global GDP. Since 2013, China has poured more than one trillion dollars into infrastructure and energy projects, often financed through opaque and high-interest loans that have driven countries like Sri Lanka, Zambia, and Pakistan to the brink of default. Across Africa alone, Chinese lending has exceeded 160 billion dollars since 2000, while Russia has expanded its reach in Latin America through arms deals, energy projects, and disinformation networks, reviving Cold War-era alignments in Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua. The result is clear. The moral advantage that once distinguished the United States and its allies has eroded. As Washington dismantles key instruments of soft power, from development aid and public diplomacy to democracy promotion programs, authoritarian powers are filling the void. America’s challenge is no longer simply to outspend or outmaneuver its rivals. It is to reclaim the moral credibility that once made its leadership aspirational.

Power Is Not Enough

As I noted earlier, the United States has won more friends with soft-power tools than with military might, and that strength rests on moral leadership. Moral leadership draws friends through cooperation and partnership. Global health initiatives have strengthened health systems, reduced child mortality, and expanded access to vaccines in some of the world’s most vulnerable regions. Educational and cultural exchange programs like Fulbright, International Visitor Leadership, and English-language learning initiatives have fostered generations of leaders who understand and engage with democratic norms. Development efforts that support independent media, civil society, and electoral integrity have helped communities build accountable institutions. Humanitarian assistance and disaster-relief missions have saved lives and built trust long after the crisis fades. Even public-diplomacy programs, from libraries to digital-literacy workshops, have opened doors where formal diplomacy falters. And these investments do not simply support communities in the moment; they multiply.

For instance, when a girl learns to read, she grows into a woman who votes, earns, leads, and ultimately reshapes the future of her family and her society. Around the world, programs that expand girls’ access to education have raised literacy, lowered child marriage, strengthened public health, and opened economic doors where none previously existed. Even in Afghanistan, despite the Taliban’s return, there remains a generation of educated women determined to carry the torch forward. They have built underground classrooms, community tutoring circles, and quiet learning networks that keep the promise of education alive for the next generation of girls. These are the kinds of investments that reflect the best of American soft power, answering the enduring global demand for justice, dignity, and democratic accountability.

And the influence of these values runs deeper than many realize. Even America’s fiercest critics still appeal to the very moral and legal standards rooted in the international norms the United States helped shape. This is why authoritarian regimes from North Korea to Iran to Venezuela stage carefully managed “elections” to claim legitimacy. They know the global system now expects governments to present themselves as democratic, even when they are not. Even the world’s most repressive states feel pressure to project compliance with the expectations of a rules-based order, one still shaped in no small part by the Wilsonian principles that elevated democracy, law, and legitimacy as global standards.

But as powerful as these tools are, soft power alone cannot meet a world reshaped by new grievances, new technological disruptions, and new doubts about Western sincerity. To endure, moral leadership must be matched by institutions and policies that are visibly fair, consistent, and accountable. If the United States hopes to retain even a measure of moral leadership in this century, it must recognize that the old playbook can no longer guide a world in upheaval. A new brand of liberalism must be reimagined for a fragmented world, one that trades old certainties for a more inclusive, justice-centered vision of global leadership. In an era defined by ruptures and realignments, moral authority flows not from power, but from the courage to imagine something fairer than what came before. It requires listening before prescribing, partnering rather than dictating, and treating dignity itself as a geopolitical force.

The world is no longer organized around Cold War binaries of democracy versus authoritarianism. It is multipolar, entangled, and shaken by overlapping crises that no ideology can contain. The divide between the Global North and Global South has widened, not because their values are incompatible, but because too many partnerships have been transactional, conditional, or paternalistic. Countries increasingly want relationships that acknowledge their agency and complexity instead of sorting them into ideological camps.

In 2025, they are more vital than ever as the world once again confronts war and war crimes across the globe. Without them, where and how would we preserve our shared sense of

Within this reimagined liberalism, true equality will only be reached when we no longer need “Global North” and “Global South” as descriptors at all, when partnership, dignity, and justice erase the hierarchies those terms imply. This moment calls for a pluralist values diplomacy anchored in fairness, inclusion, and humility. Pluralist values diplomacy respects cultural difference without surrendering universal rights, insisting that diversity of context is compatible with universality of dignity.

That means building coalitions around justice, not just democracy. While political systems differ, people everywhere share a desire for honest governance, fair courts, women’s rights, safe communities, and accountable institutions. These universal aspirations offer a more durable foundation for partnership than any narrow focus on electoral models. When the United States collaborates on anti-corruption, gender equality, labor protections, climate resilience, or ending impunity, it forms alliances rooted in shared moral purpose rather than political alignment, alliances that endure because they are built on justice, not coercion.

And the pillars of moral leadership have evolved. Human rights, climate justice, and digital ethics now define the frontier of global influence. Defending activists, supporting climate-impacted communities, particularly those in the Global South who bear the greatest burdens with the fewest resources, and shaping fair rules for artificial intelligence and data privacy are not peripheral concerns. They are the arenas where legitimacy is earned. The nations that approach these challenges with integrity, rather than expediency, will shape the moral architecture of this century.

The United States can still lead. But doing so requires humility, partnership, strategic clarity, and the kind of foresight that looks beyond immediate wins to long-term legitimacy. In a fractured world, moral authority belongs to those willing to reimagine it and to lead with purpose rather than the reflexes of power. To move toward this new liberalism, as outlined above, we need less triumphalism and more listening. And that listening must be universal, across societies, across political systems, and across histories. Countries everywhere deserve to be heard, but the responsibility is especially great for nations like the United States and the European Union, which so often claim to champion human rights, democracy, and justice. Moral leadership begins at home, and we cannot export values we have not secured for our own people.

This means addressing systemic economic and social inequality, from the chronic underfunding of marginalized communities in the United States to the widening wealth gap and austerity backlash seen across parts of Europe. It means confronting racism and reckoning honestly with the legacies of slavery and colonialism, whether in debates about reparations in the U.S. or rising demands for historical accountability in former European empires like France, Belgium, and the United Kingdom. It means building immigration systems that are humane, just, and fair, especially as countries grapple with crises like the U.S.–Mexico border, the Mediterranean migrant tragedies, and increasingly militarized responses to refugees fleeing conflict or climate disaster. And it means ensuring that no one is above the law, whether that is American elites evading accountability during financial scandals or European leaders excusing corruption in the name of national security.

To build a global order capable of sustaining this reimagined liberalism, we need leadership rooted in empathy, not paternalism, not the old habit of “do as I say, not as I do.” That approach has never worked, and it will not work now. And, crucially, it requires strengthening global mechanisms of accountability and upholding international norms so that no state receives a free pass for human rights violations, regardless of its strategic value or political alliance. Whether it is overlooking abuses committed by close allies in the Middle East, excusing democratic backsliding in countries like Hungary and India, or selectively invoking human rights against geopolitical rivals, the world sees the double standards. And as we allow those double standards to persist, we erode the very Wilsonian-inspired global order we claim to defend, even in its imperfect form.

The Mission Never Ends

Maybe I am naïve, but even as Wilsonian ideals falter, we cannot let them disappear. Because when we lose them, we lose the best of what we aspire to be, not just as nations, but as a global community. The belief in freedom, justice, stability, and rights for all is not a pipe dream. It is the lifeblood of hope for millions. Whether it is citizens casting ballots in fragile democracies, women and girls gaining access to education, or people free to love whom they choose, these are not abstractions. They are the lived expressions of a vision that insists peace and progress flow from dignity, participation, and the rule of law. Yes, these principles may be bruised, inconsistently applied, or mocked by cynics who see only power, not purpose, but they remain the closest thing we have to a moral compass in a fractured world. If we abandon them, we surrender the very horizon that once allowed us to imagine something bigger than borders, stronger than alliances, and more enduring than any single nation’s interests.

Yet the call to make the world more just remains central to the American identity in global affairs. When that voice goes silent, we lose more than moral authority. We lose our capacity to inspire, to innovate, and to shape a world that reflects both our interests and our ideals. I often reflect on my work with USAID and as an implementer of U.S. Government programs, and I remember how gratifying it was to see our efforts give people second chances, or a first chance altogether. I have seen these ideals not in textbooks but in the faces of the people we served. Whether it was meeting women entrepreneurs in Central Asia who sought to empower other women to escape cycles of domestic violence through entrepreneurship, training Supreme Court judges in Kazakhstan to strengthen the rule of law, fostering peace and reconciliation in Bosnia and Herzegovina by supporting efforts to locate the missing from the wars of the 1990s, or helping Nicaraguan civil society hold the Ortega-Murillo regime accountable for human rights abuses, Americans were there, hand in hand, standing for something larger than ourselves.

That is the America the world still wants to believe in, and the one we must fight to be again. In a time of cynicism, the choice is not between idealism and realism. It is between leading with meaning or fading into irrelevance. An “America First” agenda should never mean isolating ourselves from the world, cutting aid programs, or ceding influence to China and Russia. It must mean the opposite, putting the United States in a position to lead, to engage, and to shape the global future at every conceivable opportunity. Unless the United States chooses that course, the American empire will become a hollow echo of its former self, remembered only in the pages of history, alongside other once-glorious empires that mistook power for purpose.

humanity? Though often entangled in politics, international justice mechanisms remain essential for holding both states and non-state actors accountable. History offers powerful reminders of their necessity. Without the Nuremberg Trials, countless Nazi perpetrators would have escaped justice for committing some of humanity’s darkest crimes. Without the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), many victims of genocide in Bosnia and Herzegovina would never have known the fate of their children, spouses, siblings, or parents.

American leadership depends on defending, not bypassing, these institutions, for they embody the very ideals of justice, dignity, and the rule of law that the United States claims to champion. The U.S. played a central role in shaping this global architecture of accountability, from leading the Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials to supporting the establishment of the ICTY and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), both precursors to the International Criminal Court (ICC). While Washington has yet to fully embrace ICC membership, its historical commitment to justice helped lay the groundwork for the Court’s creation under the Rome Statute in 2002.

However, in recent years, the United States has backtracked on many of these efforts, at times even undermining the very institutions it helped build. By rejecting the authority of international courts, sanctioning ICC officials, and applying double standards in accountability, America risks eroding the credibility of the global justice system it once championed. After all, why should perpetrators of war crimes in Sudan, such as Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemedti) and other Rapid Support Forces commanders accused of orchestrating atrocities in Darfur and across Sudan, be held accountable if U.S. allies like Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and senior Israeli defense officials are not? When accountability becomes selective, justice devolves into political theater. Justice that is uneven or lopsided is not justice at all. Delegitimizing these institutions weakens the very international order that Wilsonians sought to sustain, an order rooted in law, moral leadership, and shared responsibility. To preserve that order, nations must recommit to universal principles of justice and accountability, ensuring that international law applies not only to the weak, but to the powerful as well. That is global primacy, not selective application.

The Crisis of Wilsonianism

After the Cold War, the United States embarked on what became known as the freedom agenda, a sweeping vision to promote democracy, free markets, and human rights as the cornerstones of a stable world order. Rooted in the belief that democratic governance would naturally lead to peace and prosperity, it reflected America’s conviction that its model could and should be replicated globally. In theory, it was a moral mission; in practice, it often blurred the line between idealism and interventionism. In the wake of 9/11, this agenda took on a militant edge, manifesting most visibly in Iraq and Afghanistan. The effort to implant democracy in societies fractured by conflict, colonial legacies, and sectarian divides proved both ill-timed and ill-prepared. What followed was not the triumph of liberty, but a sobering lesson in overreach.

Washington’s vision became clouded by arrogance and moral hegemony, the assumption that democracy could be imposed from above and would automatically take hold once authoritarian regimes were removed. The U.S. congressional reports that followed the Iraq invasion exposed these failures in stark detail: faulty intelligence, poor post-war planning, and a deep misunderstanding of Iraq’s political and social fabric. Toppling Saddam Hussein did not bring democracy; it unleashed chaos, sectarianism, and widespread disillusionment with the very ideals America sought to promote.

The tragic return of the Taliban in Afghanistan stands as an equally harsh reminder of what happens when democracy is imposed rather than cultivated. After two decades of war, nation-building, and promises of freedom, Afghanistan reverted to authoritarian rule almost overnight, revealing the fragility of institutions built on foreign scaffolding rather than local legitimacy.

After all, democracy is not an exportable commodity but a lived conviction, one that can only endure when people themselves desire it, nurture it, and fight for it. This truth is evident in the Arab Spring, when citizens across the Middle East and North Africa rose up to demand dignity, justice, and reform. Their courage proved that the yearning for freedom must come from within, yet their struggles also showed how fragile democracy remains when hope outpaces institutions. This tension is often at the heart of criticism directed at U.S. democracy and governance programs. Skeptics argue that initiatives funded by USAID, the State Department’s DRL Bureau, and other Western donors can cross the line into social engineering or political interference. These critiques gain traction in places where local histories are marked by colonialism, foreign interventions, or Cold War proxy battles. But the deeper truth is that no external actor can impose democracy where people do not want it, and no external actor can extinguish it where they do.

This lesson is deeply germane to the American experience, born of struggle, dissent, and a collective insistence on self-governance. Even with a Constitution in place, women’s rights and civil rights for all were not granted easily; they had to be fought for, won through persistence, protest, and sacrifice. The enduring truth is clear. Democracy cannot be delivered by drone or decree. It must be demanded, defended, and defined by the people themselves.

This question lies at the heart of America’s modern identity crisis. The United States has long defined its leadership through the language of freedom, human rights, and democracy, yet its credibility gap has widened as it grapples with internal divisions and authoritarian impulses that mirror the very forces it claims to oppose abroad. The January 6th insurrection, rising corruption, deep racial and partisan polarization, and persistent voter suppression have exposed cracks in America’s democratic foundation. These are not isolated issues but signs of institutional fragility and moral drift. The attack on the Capitol was more than an assault on a building. It was an assault on the peaceful transfer of power, revealing how disinformation, extremism, and populist rage can erode democracy from within. Even more alarming, efforts to pardon or glorify January 6th insurrectionists further normalize political violence and contempt for democratic accountability. When acts of sedition are recast as patriotism, the rule of law is not merely weakened; it is inverted.

Meanwhile, the influence of money in politics, gerrymandering, and restrictive voting laws has further undermined public trust, as once-neutral institutions like the courts, press, and electoral system have become partisan battlegrounds. This climate of division and fear has created fertile ground for authoritarian tendencies to take root, replacing dialogue with resentment and democratic compromise with contempt.

This erosion of integrity underscores the danger of performative moralism, a foreign policy that preaches justice abroad while failing to uphold it at home. When moral rhetoric is not matched by institutional consistency, it becomes hollow, a performance rather than a principle. The defunding of USAID and the U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP), the downgrading of the State Department’s Human Rights Report, and politically motivated claims of genocide, such as those leveled against South Africa while ignoring actual genocides elsewhere, only deepen this hypocrisy. When ideals are wielded for convenience, values become slogans, and leadership turns into theater. To reclaim credibility, America must restore institutional integrity and live by the same moral standards it demands of others, leading not by proclamation, but through principled example.

Predictably, this double standard and erosion of moral credibility have not gone unnoticed. Russia, China, and Iran have emerged as the loudest critics of Western hypocrisy, exploiting America’s contradictions to expand their global influence. They cast the West’s promotion of democracy and human rights as selective and self-serving, and too often, that narrative resonates. Having served in a country like Nicaragua, I witnessed firsthand how governments isolated by U.S. and EU sanctions sought political and economic refuge through alliances with Moscow and Beijing. For illiberal regimes, such partnerships provide both survival and legitimacy, filling the moral vacuum left by Western inconsistency.

China, in particular, has seized this opening through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which now involves over 150 countries, representing nearly two-thirds of the world’s population and about 40 percent of global GDP. Since 2013, China has poured more than one trillion dollars into infrastructure and energy projects, often financed through

opaque and high-interest loans that have driven countries like Sri Lanka, Zambia, and Pakistan to the brink of default. Across Africa alone, Chinese lending has exceeded 160 billion dollars since 2000, while Russia has expanded its reach in Latin America through arms deals, energy projects, and disinformation networks, reviving Cold War-era alignments in Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua. The result is clear. The moral advantage that once distinguished the United States and its allies has eroded. As Washington dismantles key instruments of soft power, from development aid and public diplomacy to democracy promotion programs, authoritarian powers are filling the void. America’s challenge is no longer simply to outspend or outmaneuver its rivals. It is to reclaim the moral credibility that once made its leadership aspirational.

Power Is Not Enough

As I noted earlier, the United States has won more friends with soft-power tools than with military might, and that strength rests on moral leadership. Moral leadership draws friends through cooperation and partnership. Global health initiatives have strengthened health systems, reduced child mortality, and expanded access to vaccines in some of the world’s most vulnerable regions. Educational and cultural exchange programs like Fulbright, International Visitor Leadership, and English-language learning initiatives have fostered generations of leaders who understand and engage with democratic norms. Development efforts that support independent media, civil society, and electoral integrity have helped communities build accountable institutions. Humanitarian assistance and disaster-relief missions have saved lives and built trust long after the crisis fades. Even public-diplomacy programs, from libraries to digital-literacy workshops, have opened doors where formal diplomacy falters. And these investments do not simply support communities in the moment; they multiply.

For instance, when a girl learns to read, she grows into a woman who votes, earns, leads, and ultimately reshapes the future of her family and her society. Around the world, programs that expand girls’ access to education have raised literacy, lowered child marriage, strengthened public health, and opened economic doors where none previously existed. Even in Afghanistan, despite the Taliban’s return, there remains a generation of educated women determined to carry the torch forward. They have built underground classrooms, community tutoring circles, and quiet learning networks that keep the promise of education alive for the next generation of girls. These are the kinds of investments that reflect the best of American soft power, answering the enduring global demand for justice, dignity, and democratic accountability.

And the influence of these values runs deeper than many realize. Even America’s fiercest critics still appeal to the very moral and legal standards rooted in the international norms the United States helped shape. This is why authoritarian regimes from North Korea to Iran to Venezuela stage carefully managed “elections” to claim legitimacy. They know the global system now expects governments to present themselves as democratic, even when they are not. Even the world’s most repressive states feel pressure to project compliance with the expectations of a rules-based order, one still shaped in no small part by the Wilsonian principles that elevated democracy, law, and legitimacy as global standards.

But as powerful as these tools are, soft power alone cannot meet a world reshaped by new grievances, new technological disruptions, and new doubts about Western sincerity. To endure, moral leadership must be matched by institutions and policies that are visibly fair, consistent, and accountable. If the United States hopes to retain even a measure of moral leadership in this century, it must recognize that the old playbook can no longer guide a world in upheaval. A new brand of liberalism must be reimagined for a fragmented world, one that trades old certainties for a more inclusive, justice-centered vision of global leadership. In an era defined by ruptures and realignments, moral authority flows not from power, but from the courage to imagine something fairer than what came before. It requires listening before prescribing, partnering rather than dictating, and treating dignity itself as a geopolitical force.

The world is no longer organized around Cold War binaries of democracy versus authoritarianism. It is multipolar, entangled, and shaken by overlapping crises that no ideology can contain. The divide between the Global North and Global South has widened, not because their values are incompatible, but because too many partnerships have been transactional, conditional, or paternalistic. Countries increasingly want relationships that acknowledge their agency and complexity instead of sorting them into ideological camps.

Within this reimagined liberalism, true equality will only be reached when we no longer need “Global North” and “Global South” as descriptors at all, when partnership, dignity, and justice erase the hierarchies those terms imply. This moment calls for a pluralist values diplomacy anchored in fairness, inclusion, and humility. Pluralist values diplomacy respects cultural difference without surrendering universal rights, insisting that diversity of context is compatible with universality of dignity.

That means building coalitions around justice, not just democracy. While political systems differ, people everywhere share a desire for honest governance, fair courts, women’s rights, safe communities, and accountable institutions. These universal aspirations offer a more durable foundation for partnership than any narrow focus on electoral models. When the United States collaborates on anti-corruption, gender equality, labor protections, climate resilience, or ending impunity, it forms alliances rooted in shared moral purpose rather than political alignment, alliances that endure because they are built on justice, not coercion.

And the pillars of moral leadership have evolved. Human rights, climate justice, and digital ethics now define the frontier of global influence. Defending activists, supporting climate-impacted communities, particularly those in the Global South who bear the greatest burdens with the fewest resources, and shaping fair rules for artificial intelligence and data privacy are not peripheral concerns. They are the arenas where legitimacy is earned. The nations that approach these challenges with integrity, rather than expediency, will shape the moral architecture of this century.

The United States can still lead. But doing so requires humility, partnership, strategic clarity, and the kind of foresight that looks beyond immediate wins to long-term legitimacy. In a fractured world, moral authority belongs to those willing to reimagine it and to lead with purpose rather than the reflexes of power. To move toward this new liberalism, as outlined above, we need less triumphalism and more listening. And that listening must be universal, across societies, across political systems, and across histories. Countries everywhere deserve to be heard, but the responsibility is especially great for nations like the United States and the European Union, which so often claim to champion human rights, democracy, and justice. Moral leadership begins at home, and we cannot export values we have not secured for our own people.

This means addressing systemic economic and social inequality, from the chronic underfunding of marginalized communities in the United States to the widening wealth gap and austerity backlash seen across parts of Europe. It means confronting racism and reckoning honestly with the legacies of slavery and colonialism, whether in debates about reparations in the U.S. or rising demands for historical accountability in former European empires like France, Belgium, and the United Kingdom. It means building immigration systems that are humane, just, and fair, especially as countries grapple with crises like the U.S.–Mexico border, the Mediterranean migrant tragedies, and increasingly militarized responses to refugees fleeing conflict or climate disaster. And it means ensuring that no one is above the law, whether that is American elites evading accountability during financial scandals or European leaders excusing corruption in the name of national security.

To build a global order capable of sustaining this reimagined liberalism, we need leadership rooted in empathy, not paternalism, not the old habit of “do as I say, not as I do.” That approach has never worked, and it will not work now. And, crucially, it requires strengthening global mechanisms of accountability and upholding international norms so that no state receives a free pass for human rights violations, regardless of its strategic value or political alliance. Whether it is overlooking abuses committed by close allies in the Middle East, excusing democratic backsliding in countries like Hungary and India, or selectively invoking human rights against geopolitical rivals, the world sees the double standards. And as we allow those double standards to persist, we erode the very Wilsonian-inspired global order we claim to defend, even in its imperfect form.

The Mission Never Ends

Maybe I am naïve, but even as Wilsonian ideals falter, we cannot let them disappear. Because when we lose them, we lose the best of what we aspire to be, not just as nations, but as a global community. The belief in freedom, justice, stability, and rights for all is not a pipe dream. It is the lifeblood of hope for millions. Whether it is citizens casting ballots in fragile democracies, women and girls gaining access to education, or people free to love whom they choose, these are not abstractions. They are the lived expressions of a vision that insists peace and progress flow from dignity, participation, and the rule of law. Yes, these principles may be bruised, inconsistently applied, or mocked by cynics who see only power, not purpose, but they remain the closest thing we have to a moral compass in a fractured world. If we abandon them, we surrender the very horizon that once allowed us to imagine something bigger than borders, stronger than alliances, and more enduring than any single nation’s interests.

Yet the call to make the world more just remains central to the American identity in global affairs. When that voice goes silent, we lose more than moral authority. We lose our capacity to inspire, to innovate, and to shape a world that reflects both our interests and our ideals. I often reflect on my work with USAID and as an implementer of U.S. Government programs, and I remember how gratifying it was to see our efforts give people second chances, or a first chance altogether. I have seen these ideals not in textbooks but in the faces of the people we served. Whether it was meeting women entrepreneurs in Central Asia who sought to empower other women to escape cycles of domestic violence through entrepreneurship, training Supreme Court judges in Kazakhstan to strengthen the rule of law, fostering peace and reconciliation in Bosnia and Herzegovina by supporting efforts to locate the missing from the wars of the 1990s, or helping Nicaraguan civil society hold the Ortega-Murillo regime accountable for human rights abuses, Americans were there, hand in hand, standing for something larger than ourselves.

That is the America the world still wants to believe in, and the one we must fight to be again. In a time of cynicism, the choice is not between idealism and realism. It is between leading with meaning or fading into irrelevance. An “America First” agenda should never mean isolating ourselves from the world, cutting aid programs, or ceding influence to China and Russia. It must mean the opposite, putting the United States in a position to lead, to engage, and to shape the global future at every conceivable opportunity. Unless the United States chooses that course, the American empire will become a hollow echo of its former self, remembered only in the pages of history, alongside other once-glorious empires that mistook power for purpose.

Recommended

Why the Cold War Never Ended in the Kremlin

How Warsaw and Kyiv Anchor Europe’s Defense

Orban Inside the Union, Against the Union

How the War in Ukraine Redefined Europe?

The Machinery of Wealth and Obedience