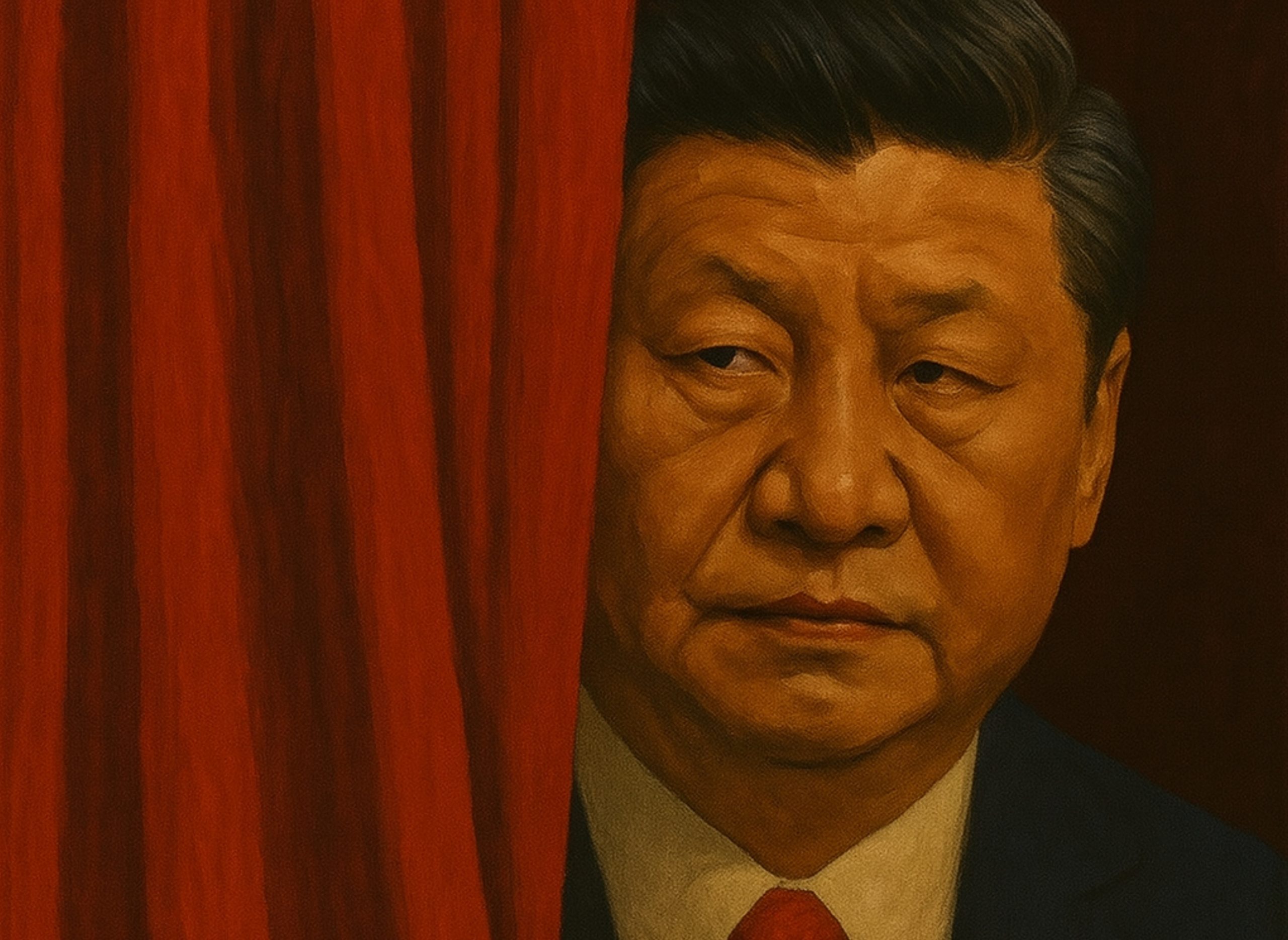

Xi Jinping’s leadership is transforming modern China with a pace and intensity that have shocked the world. Since seizing power in 2012 as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), and later in 2013 as President of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Xi has radically altered China’s international posture. His predecessors, Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin, largely followed the path set by Deng Xiaoping, maintaining a low-profile foreign policy under the guiding motto taoguang yanghui: “hide your strength, bide your time.” This strategy aimed to avoid direct confrontation with major powers while focusing on domestic development and expanding influence quietly.

It was a period marked by opening to the world: a friendlier foreign policy was paired with a somewhat looser grip on domestic affairs, designed to stimulate economic growth in line with the post–Cold War neoliberal atmosphere of the time, although always within the limits set by the Party. With Xi’s rise, this approach shifted dramatically. From the start, he pursued a more assertive foreign policy, determined to enhance China’s image as a modern superpower and signal to other major powers that the PRC would defend its geopolitical interests globally. As the ancient Chinese classic, the I Ching, counsels: “To cross the great river, all forces must harmonize and converge.” For China, such global ambitions require domestic unity.

In Xi’s political vision, harmony between state and society is built on the people’s belief in their government. In the Chinese political context, that belief is cultivated through centralized authority, ideological messaging, economic achievement, and subtle but pervasive control over information, made possible by advanced cyber-surveillance technologies. This hyper-centralized governance has been reinforced by sweeping political reforms: anti-corruption campaigns that doubled as purges of rivals, legal changes abolishing presidential term limits, and structural moves to consolidate power in Xi’s hands. While this centralization recalls Mao Zedong’s personalist rule, Xi wields tools Mao never had: modern digital technology, global economic integration, and real-time surveillance. Yet it would be a mistake to view Xi’s governance as entirely opposed to that of his predecessors. His approach is less a rejection than a reconfiguration, a different path to the same ultimate goal: elevating China to the status of a leading world superpower.

Xi’s Power Grab

After the turbulence of Mao’s personalist rule, Deng Xiaoping and his allies designed guardrails to prevent another strongman. These included the two-term limit for the state presidency in the 1982 PRC constitution, power rotation and mandatory retirement ages for Party and military leaders, and collective leadership through the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC), where authority was shared among seven to nine members, with the General Secretary “first among equals.” There was also, at least partially, a separation of top Party, state, and military posts. The goal was smooth succession, as seen in the Jiang-to-Hu transition in 2002 and Hu-to-Xi in 2012, reducing the risk of policy being driven by one man’s whims.

In short: power was to be spread like rice in a bowl: enough for everyone, never piled on one plate. Jiang Zemin (1989–2002), who rose during the Tiananmen crisis, relied on factional balancing through the Shanghai clique, a network of top officials from the city that helped shape policy priorities. Jiang pursued taoguang yanghui abroad while letting technocrats and ministers manage their portfolios at home, making the PSC a true decision-making body. Hu Jintao (2002–2012) favored low-key, consensus-driven governance under the slogan of “scientific development.” Power was fragmented between the premier, vice premiers, and PSC members who oversaw separate policy areas.

holds a master’s degree in East Asian Studies from the University of Groningen, Netherlands. His main areas of research are Chinese foreign policy, China-Russia relations, EU-China relations, and the Asia-Pacific region.

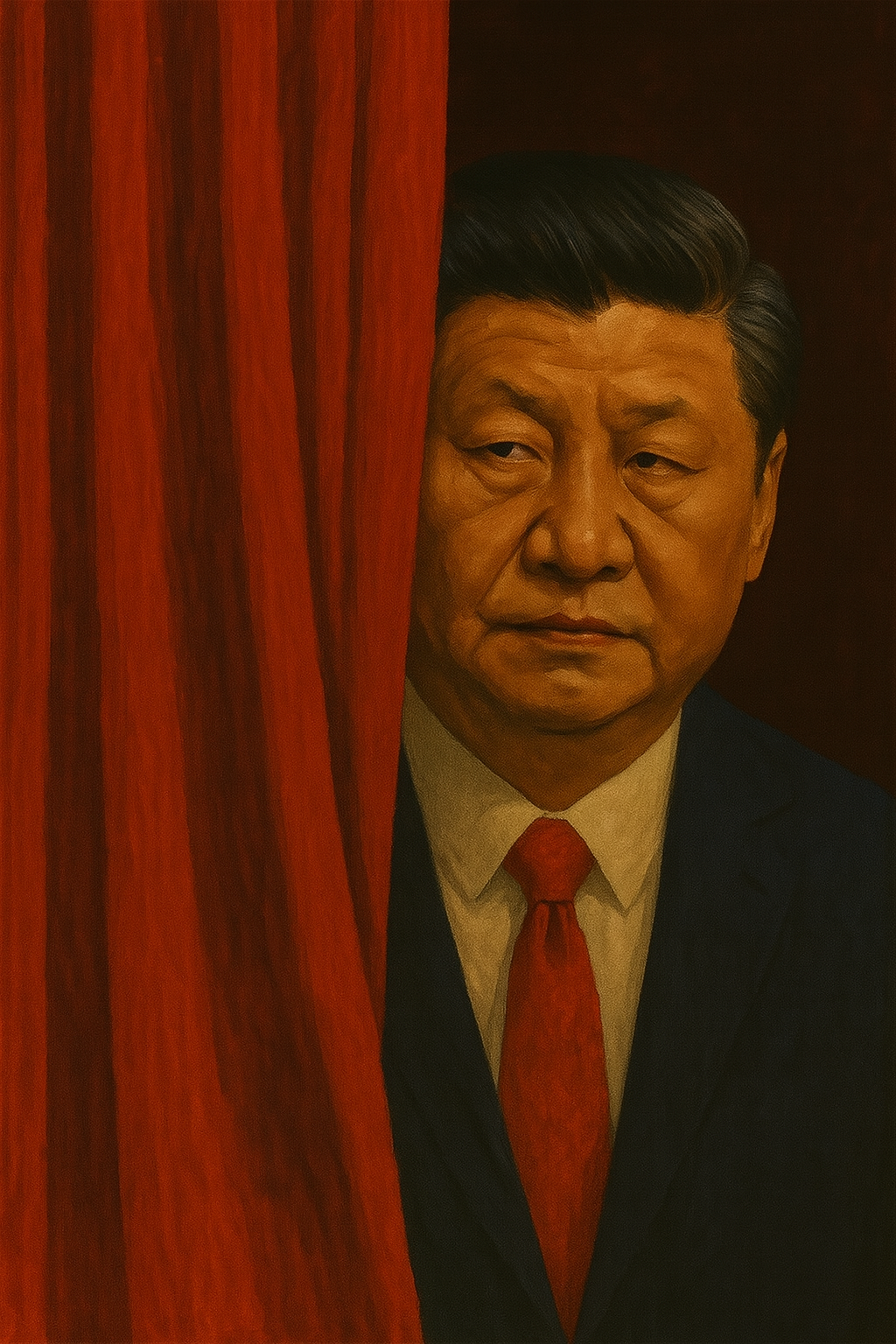

State media saturates its coverage with Xi’s activities, speeches, and symbolic gestures, turning the daily news cycle into a constant reaffirmation of his leadership and vision. The cultivation of a personality cult around Xi is deliberate and highly organized. His portrait hangs in government buildings, classrooms, and rural village squares. Large-scale exhibitions and documentary series present him as the wise strategist behind China’s successes, while his writings, compiled in multi-volume sets such as The Governance of China, are published in multiple languages and distributed widely at home and abroad.

Public rituals further reinforce loyalty: officials take oaths in front of the Party flag, reciting pledges to uphold Xi’s thought as part of their duty to the nation. This phenomenon carries echoes of Mao’s cult of personality, though in a modernized form. Where Mao’s image was spread through mass rallies, revolutionary songs, and a pocket-sized “Little Red Book,” Xi’s image and ideas travel through broadcast television, curated online platforms, and big-data-driven propaganda. His cult is less about spontaneous mass fervor and more about a carefully managed, top-down strategy to ensure ideological conformity and personal loyalty.

By intertwining his personal authority with the Party’s official doctrine, Xi has positioned dissent not only as a political offense but as an ideological betrayal. In the CCP’s current political climate, to question Xi’s leadership is to question the Party’s legitimacy itself. This fusion of ideology and personality strengthens Xi’s grip on power, making him not just the chief executive of the state but the symbolic embodiment of China’s future. It also creates a political environment in which the boundaries between loyalty to the nation, loyalty to the Party, and loyalty to Xi Jinping have been deliberately blurred, and in which the leader stands firmly at the center of all three.

Digital Authoritarianism

If Mao Zedong built his power through revolutionary fervor and mass mobilization, Xi Jinping has harnessed the quieter, more pervasive force of data. Under Xi’s leadership, China has developed a new model of governance that uses technology not only to deliver services and maintain public order but also to monitor, discipline, and shape the behavior of its citizens. This is the essence of what many analysts call “digital authoritarianism”: a fusion of state power, Party control, and cutting-edge technology to achieve near-total information dominance. One of the most ambitious elements of this system is the Social Credit System (SCS).

Officially, it is described as a way to “build trust” in society by rewarding lawful and honest behavior while punishing fraud, corruption, and misconduct. In practice, it functions as a broad behavioral scoring framework, drawing on data from courts, financial institutions, e-commerce platforms, and local government records. High scores can mean easier access to loans or priority in school admissions, while low scores can result in travel restrictions, public blacklisting, and even reduced internet speeds. While not yet fully centralized nationwide, various regional pilot programs have already demonstrated the system’s ability to link compliance with the Party’s directives to tangible rewards and punishments.

State media saturates its coverage with Xi’s activities, speeches, and symbolic gestures, turning the daily news cycle into a constant reaffirmation of his leadership and vision. The cultivation of a personality cult around Xi is deliberate and highly organized. His portrait hangs in government buildings, classrooms, and rural village squares. Large-scale exhibitions and documentary series present him as the wise strategist behind China’s successes, while his writings, compiled in multi-volume sets such as The Governance of China, are published in multiple languages and distributed widely at home and abroad.

Public rituals further reinforce loyalty: officials take oaths in front of the Party flag, reciting pledges to uphold Xi’s thought as part of their duty to the nation. This phenomenon carries echoes of Mao’s cult of personality, though in a modernized form. Where Mao’s image was spread through mass rallies, revolutionary songs, and a pocket-sized “Little Red Book,” Xi’s image and ideas travel through broadcast television, curated online platforms, and big-data-driven propaganda. His cult is less about spontaneous mass fervor and more about a carefully managed, top-down strategy to ensure ideological conformity and personal loyalty.

By intertwining his personal authority with the Party’s official doctrine, Xi has positioned dissent not only as a political offense but as an ideological betrayal. In the CCP’s current political climate, to question Xi’s leadership is to question the Party’s legitimacy itself. This fusion of ideology and personality strengthens Xi’s grip on power, making him not just the chief executive of the state but the symbolic embodiment of China’s future. It also creates a political environment in which the boundaries between loyalty to the nation, loyalty to the Party, and loyalty to Xi Jinping have been deliberately blurred, and in which the leader stands firmly at the center of all three.

Digital Authoritarianism

If Mao Zedong built his power through revolutionary fervor and mass mobilization, Xi Jinping has harnessed the quieter, more pervasive force of data. Under Xi’s leadership, China has developed a new model of governance that uses technology not only to deliver services and maintain public order but also to monitor, discipline, and shape the behavior of its citizens. This is the essence of what many analysts call “digital authoritarianism”: a fusion of state power, Party control, and cutting-edge technology to achieve near-total information dominance. One of the most ambitious elements of this system is the Social Credit System (SCS).

Officially, it is described as a way to “build trust” in society by rewarding lawful and honest behavior while punishing fraud, corruption, and misconduct. In practice, it functions as a broad behavioral scoring framework, drawing on data from courts, financial institutions, e-commerce platforms, and local government records. High scores can mean easier access to loans or priority in school admissions, while low scores can result in travel restrictions, public blacklisting, and even reduced internet speeds. While not yet fully centralized nationwide, various regional pilot programs have already demonstrated the system’s ability to link compliance with the Party’s directives to tangible rewards and punishments.

Beyond the SCS, Xi’s era has seen an unprecedented expansion of surveillance infrastructure. China now operates one of the world’s largest networks of CCTV cameras, many equipped with advanced facial recognition technology. These systems are integrated with artificial intelligence to identify individuals in real time, track their movements, and even analyze patterns of association. Mobile phone tracking, mandatory real-name registration for online accounts, and the monitoring of messaging apps like WeChat extend the reach of the state into the private sphere of communication. Information control is another pillar of this digital regime.

The Great Firewall, China’s elaborate system of internet censorship, has become more sophisticated under Xi, not only blocking foreign websites but also actively filtering domestic content. Entire narratives can be erased within hours, replaced by state-approved interpretations. Independent journalism, already under pressure before Xi’s tenure, has been pushed to the margins, while NGOs, religious groups, and online communities have been subjected to tight regulations or outright closures. This digital architecture has also made repression less visible. Unlike the mass arrests or public trials of earlier decades, dissent today is often smothered before it becomes organized.

Posts disappear, accounts are deactivated, and individuals receive quiet visits from security officials warning them about their activities. Protests that do occur are quickly contained, with organizers monitored or detained in ways that leave little public trace. This has created what some scholars call “authoritarianism without dissent”, not because discontent has vanished, but because the space for it to manifest publicly has been almost entirely eliminated. Xi’s digital authoritarianism serves multiple purposes. It strengthens the Party’s monopoly on information, gives the leadership an unparalleled capacity for social engineering, and reinforces the image of a state that is omnipresent and omniscient. In the eyes of its architects, it is a tool for stability, efficiency, and even modernization. But it also represents a fundamental shift in the nature of authoritarian control: the ability to maintain power not only through force or ideology, but through the constant, invisible shaping of everyday life.

The New Face of State Capitalism

In Xi Jinping’s China, economics is not merely about growth. It is a political instrument, a lever to reinforce Party authority and align the private sector with state priorities. While China has been officially “socialist” since 1949, the reform era under Deng Xiaoping and his successors allowed market forces and private enterprise to flourish in ways that sometimes operated beyond direct political control. Xi has moved to close that gap, reshaping the country’s economic model into a form of state capitalism with Chinese characteristics, where the market exists to serve the strategic and ideological goals of the Party.

This transformation has been most visible in the crackdown on major private firms. Tech giants like Alibaba, Tencent, Didi, and Meituan, once symbols of Chinese entrepreneurial dynamism, have faced heavy regulatory penalties, forced restructuring, and public rebukes. The official narrative frames these moves as necessary to curb monopolistic behavior, protect data security, and promote “Common Prosperity,” a slogan Xi has elevated into a central policy doctrine. The deeper logic, however, is political: no private enterprise can be allowed to rival the Party’s influence or operate outside its guidance.

Authoritarian control now rests not just on force or ideology, but on the invisible shaping of daily life.

“Common Prosperity” is both an economic and ideological campaign. On paper, it seeks to reduce inequality and create a more balanced distribution of wealth. In practice, it reasserts the Party’s role as the ultimate arbiter of economic direction, ensuring that business elites align with state priorities or face swift consequences. Philanthropic gestures from billionaires, wage hikes in big firms, and renewed pledges to support rural revitalization all carry the unmistakable imprint of political pressure. At the same time, Xi has doubled down on strategic state intervention. Key sectors, such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence, renewable energy, and advanced manufacturing, receive targeted subsidies and state-led investment.

The “Made in China 2025” and military-civil fusion initiatives blur the line between civilian industry and defense capability, binding technological progress to national security objectives. This reassertion of state power in the economy is not a retreat to central planning of the Maoist type, but a recalibration. The private sector remains a vital engine of growth, but its autonomy is curtailed, and its survival depends on political loyalty. For Xi, economic success is inseparable from political control: a flourishing economy must be one that strengthens, rather than dilutes, the Party’s dominance. In this new model, profit is not the highest metric of success: alignment with the Party’s vision is. Under Xi, state capitalism has become not only an economic system but also a mechanism of governance, ensuring that the wealth and innovation of China’s economy are harnessed first and foremost in service of the political center.

Exporting Authoritarianism

Xi Jinping’s vision for China does not stop at its borders. While his predecessors largely adhered to taoguang yanghui, keeping a low profile abroad, Xi has embraced a more assertive role for China as both a global power and a model of governance. This includes promoting an alternative to the liberal democratic order, one in which sovereignty, stability, and economic development take precedence over political freedoms. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is the most visible vehicle for this ambition. Officially framed as a win-win infrastructure and development program, it has funded ports, railways, and power plants in over 140 countries.

But beyond cement and steel, the BRI carries political blueprints. Chinese financing often comes with fewer governance conditions than Western loans, but with deeper economic dependency. This intertwines recipient countries’ economic futures with Beijing’s strategic interests, subtly reinforcing authoritarian governance norms and discouraging alignment with democratic blocs. Alongside physical infrastructure, Xi has promoted a digital dimension to this outreach. Chinese firms export surveillance systems, facial recognition technology, and “smart city” platforms to governments seeking tighter control over their populations.

This “authoritarian tech stack” provides both tools and a governance philosophy: technology as an enabler of political dominance. At the ideological level, slogans such as the “Community of Shared Future for Mankind” and the “Global Civilization Initiative” frame China’s system as a legitimate, even superior, alternative to liberal democracy. In multilateral forums, Beijing champions principles of non-interference and regime stability, aligning itself with other authoritarian and semi-authoritarian states. Through trade, technology, and narrative diplomacy, Xi is not simply projecting Chinese influence: he is normalizing a governance model where state control and political centralization are presented as compatible with prosperity and modernization.

Fragilities and Hidden Strains

Beneath the polished image of a confident, all-powerful China under Xi Jinping lies a set of vulnerabilities that even the strongest propaganda cannot erase. The most visible pressures are economic. After decades of double-digit growth, China’s economy is slowing. Structural issues such as mounting local government debt, a property sector crisis, and sluggish consumer demand weigh heavily. Youth unemployment has reached record highs, prompting social media censorship of the statistics themselves. For a system that stakes its legitimacy on delivering prosperity, prolonged stagnation is politically dangerous.

Demographics add another layer of strain. China’s population began shrinking in 2022, and the workforce is aging rapidly. This “getting old before getting rich” dilemma threatens productivity, increases welfare burdens, and complicates long-term growth strategies. There are also political fragilities inherent in Xi’s one-man model. The dismantling of succession norms means that no clear pathway exists for leadership transition after Xi. While this consolidates his authority in the short term, it creates uncertainty, and potentially instability, in the long term. Hyper-centralization also carries a subtler risk: distorted information flows.

Subordinates may be reluctant to present bad news or alternative viewpoints, leading to decision-making blind spots. Socially, dissent has been muted, but not extinguished. From “white paper” protests against COVID lockdowns to sporadic labor unrest, pockets of resistance remind the Party that control must be constantly enforced. Maintaining this control requires ever-growing investment in surveillance and propaganda, a costly and ultimately defensive posture. The paradox is that Xi’s strength may also be his system’s weakness. By concentrating power so completely, he has made the resilience of the Chinese state more dependent than ever on the health, judgment, and political survival of one man.

Beyond the SCS, Xi’s era has seen an unprecedented expansion of surveillance infrastructure. China now operates one of the world’s largest networks of CCTV cameras, many equipped with advanced facial recognition technology. These systems are integrated with artificial intelligence to identify individuals in real time, track their movements, and even analyze patterns of association. Mobile phone tracking, mandatory real-name registration for online accounts, and the monitoring of messaging apps like WeChat extend the reach of the state into the private sphere of communication. Information control is another pillar of this digital regime.

The Great Firewall, China’s elaborate system of internet censorship, has become more sophisticated under Xi, not only blocking foreign websites but also actively filtering domestic content. Entire narratives can be erased within hours, replaced by state-approved interpretations. Independent journalism, already under pressure before Xi’s tenure, has been pushed to the margins, while NGOs, religious groups, and online communities have been subjected to tight regulations or outright closures. This digital architecture has also made repression less visible. Unlike the mass arrests or public trials of earlier decades, dissent today is often smothered before it becomes organized.

Posts disappear, accounts are deactivated, and individuals receive quiet visits from security officials warning them about their activities. Protests that do occur are quickly contained, with organizers monitored or detained in ways that leave little public trace. This has created what some scholars call “authoritarianism without dissent”, not because discontent has vanished, but because the space for it to manifest publicly has been almost entirely eliminated. Xi’s digital authoritarianism serves multiple purposes. It strengthens the Party’s monopoly on information, gives the leadership an unparalleled capacity for social engineering, and reinforces the image of a state that is omnipresent and omniscient. In the eyes of its architects, it is a tool for stability, efficiency, and even modernization. But it also represents a fundamental shift in the nature of authoritarian control: the ability to maintain power not only through force or ideology, but through the constant, invisible shaping of everyday life.

The New Face of State Capitalism

In Xi Jinping’s China, economics is not merely about growth. It is a political instrument, a lever to reinforce Party authority and align the private sector with state priorities. While China has been officially “socialist” since 1949, the reform era under Deng Xiaoping and his successors allowed market forces and private enterprise to flourish in ways that sometimes operated beyond direct political control. Xi has moved to close that gap, reshaping the country’s economic model into a form of state capitalism with Chinese characteristics, where the market exists to serve the strategic and ideological goals of the Party.

This transformation has been most visible in the crackdown on major private firms. Tech giants like Alibaba, Tencent, Didi, and Meituan, once symbols of Chinese entrepreneurial dynamism, have faced heavy regulatory penalties, forced restructuring, and public rebukes. The official narrative frames these moves as necessary to curb monopolistic behavior, protect data security, and promote “Common Prosperity,” a slogan Xi has elevated into a central policy doctrine. The deeper logic, however, is political: no private enterprise can be allowed to rival the Party’s influence or operate outside its guidance.

The paradox is that Xi’s strength may also be his system’s weakness.

The Xi Jinping era represents a decisive break from the collective leadership and restrained diplomacy that defined China’s post-Mao decades. In their place stands a political system in which power is concentrated to a degree unseen since Mao, yet fused with the mechanisms of a modern state: digital surveillance, a disciplined Party apparatus, and an economy where private enterprise survives but bows to political authority. Xi’s governance model is a hybrid, rooted in the CCP’s Leninist traditions, infused with a revived ideological narrative, and supercharged by twenty-first-century technology.

“Xi Jinping Thought” enshrines him in the Party canon alongside Mao, while a carefully curated personality cult reinforces his centrality in China’s political life. Meanwhile, the fusion of Party, state, and military leadership gives him unparalleled command over both domestic and foreign policy, enabling rapid policy execution but also creating potential blind spots. Internationally, Xi has abandoned taoguang yanghui in favor of fenfa youwei, a willingness to “strive for achievement” and assert China’s role on the global stage. Through initiatives like the Belt and Road, China is exporting not only infrastructure but also an alternative governance model: one that challenges liberal democratic norms and appeals to regimes seeking growth without political liberalization.

Yet this system is not without fragility. Economic headwinds, demographic challenges, and the inherent risks of one-man rule such as succession uncertainty, information distortion, and decision-making bottlenecks cast long shadows. In many ways, Xi’s China is both a blueprint and a warning. For some, it offers proof that authoritarian governance can thrive in the modern era; for others, it is a reminder that concentrated power, however efficient in the short term, carries the seeds of its own instability. In any case, the “Xi model” will shape not only China’s future, but the evolving global order of the twenty-first century.

“Common Prosperity” is both an economic and ideological campaign. On paper, it seeks to reduce inequality and create a more balanced distribution of wealth. In practice, it

reasserts the Party’s role as the ultimate arbiter of economic direction, ensuring that business elites align with state priorities or face swift consequences. Philanthropic gestures from billionaires, wage hikes in big firms, and renewed pledges to support rural revitalization all carry the unmistakable imprint of political pressure. At the same time, Xi has doubled down on strategic state intervention. Key sectors, such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence, renewable energy, and advanced manufacturing, receive targeted subsidies and state-led investment.

The “Made in China 2025” and military-civil fusion initiatives blur the line between civilian industry and defense capability, binding technological progress to national security objectives. This reassertion of state power in the economy is not a retreat to central planning of the Maoist type, but a recalibration. The private sector remains a vital engine of growth, but its autonomy is curtailed, and its survival depends on political loyalty. For Xi, economic success is inseparable from political control: a flourishing economy must be one that strengthens, rather than dilutes, the Party’s dominance. In this new model, profit is not the highest metric of success: alignment with the Party’s vision is. Under Xi, state capitalism has become not only an economic system but also a mechanism of governance, ensuring that the wealth and innovation of China’s economy are harnessed first and foremost in service of the political center.

Exporting Authoritarianism

Xi Jinping’s vision for China does not stop at its borders. While his predecessors largely adhered to taoguang yanghui, keeping a low profile abroad, Xi has embraced a more assertive role for China as both a global power and a model of governance. This includes promoting an alternative to the liberal democratic order, one in which sovereignty, stability, and economic development take precedence over political freedoms. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is the most visible vehicle for this ambition. Officially framed as a win-win infrastructure and development program, it has funded ports, railways, and power plants in over 140 countries.

But beyond cement and steel, the BRI carries political blueprints. Chinese financing often comes with fewer governance conditions than Western loans, but with deeper economic dependency. This intertwines recipient countries’ economic futures with Beijing’s strategic interests, subtly reinforcing authoritarian governance norms and discouraging alignment with democratic blocs. Alongside physical infrastructure, Xi has promoted a digital dimension to this outreach. Chinese firms export surveillance systems, facial recognition technology, and “smart city” platforms to governments seeking tighter control over their populations.

This “authoritarian tech stack” provides both tools and a governance philosophy: technology as an enabler of political dominance. At the ideological level, slogans such as the “Community of Shared Future for Mankind” and the “Global Civilization Initiative” frame China’s system as a legitimate, even superior, alternative to liberal democracy. In multilateral forums, Beijing champions principles of non-interference and regime stability, aligning itself with other authoritarian and semi-authoritarian states. Through trade, technology, and narrative diplomacy, Xi is not simply projecting Chinese influence: he is normalizing a governance model where state control and political centralization are presented as compatible with prosperity and modernization.

Fragilities and Hidden Strains

Beneath the polished image of a confident, all-powerful China under Xi Jinping lies a set of vulnerabilities that even the strongest propaganda cannot erase. The most visible pressures are economic. After decades of double-digit growth, China’s economy is slowing. Structural issues such as mounting local government debt, a property sector crisis, and sluggish consumer demand weigh heavily. Youth unemployment has reached record highs, prompting social media censorship of the statistics themselves. For a system that stakes its legitimacy on delivering prosperity, prolonged stagnation is politically dangerous.

Demographics add another layer of strain. China’s population began shrinking in 2022, and the workforce is aging rapidly. This “getting old before getting rich” dilemma threatens productivity, increases welfare burdens, and complicates long-term growth strategies. There are also political fragilities inherent in Xi’s one-man model. The dismantling of succession norms means that no clear pathway exists for leadership transition after Xi. While this consolidates his authority in the short term, it creates uncertainty, and potentially instability, in the long term. Hyper-centralization also carries a subtler risk: distorted information flows.

Subordinates may be reluctant to present bad news or alternative viewpoints, leading to decision-making blind spots. Socially, dissent has been muted, but not extinguished. From “white paper” protests against COVID lockdowns to sporadic labor unrest, pockets of resistance remind the Party that control must be constantly enforced. Maintaining this control requires ever-growing investment in surveillance and propaganda, a costly and ultimately defensive posture. The paradox is that Xi’s strength may also be his system’s weakness. By concentrating power so completely, he has made the resilience of the Chinese state more dependent than ever on the health, judgment, and political survival of one man.

The Xi Jinping era represents a decisive break from the collective leadership and restrained diplomacy that defined China’s post-Mao

decades. In their place stands a political system in which power is concentrated to a degree unseen since Mao, yet fused with the mechanisms of a modern state: digital surveillance, a disciplined Party apparatus, and an economy where private enterprise survives but bows to political authority. Xi’s governance model is a hybrid, rooted in the CCP’s Leninist traditions, infused with a revived ideological narrative, and supercharged by twenty-first-century technology.

“Xi Jinping Thought” enshrines him in the Party canon alongside Mao, while a carefully curated personality cult reinforces his centrality in China’s political life. Meanwhile, the fusion of Party, state, and military leadership gives him unparalleled command over both domestic and foreign policy, enabling rapid policy execution but also creating potential blind spots. Internationally, Xi has abandoned taoguang yanghui in favor of fenfa youwei, a willingness to “strive for achievement” and assert China’s role on the global stage. Through initiatives like the Belt and Road, China is exporting not only infrastructure but also an alternative governance model: one that challenges liberal democratic norms and appeals to regimes seeking growth without political liberalization.

Yet this system is not without fragility. Economic headwinds, demographic challenges, and the inherent risks of one-man rule such as succession uncertainty, information distortion, and decision-making bottlenecks cast long shadows. In many ways, Xi’s China is both a blueprint and a warning. For some, it offers proof that authoritarian governance can thrive in the modern era; for others, it is a reminder that concentrated power, however efficient in the short term, carries the seeds of its own instability. In any case, the “Xi model” will shape not only China’s future, but the evolving global order of the twenty-first century.

Recommended

How Semiconductors Shape the New World Order

A Hamiltonian Approach to Power and Foreign Policy

Why Putin and Xi Need Each Other And How the U.S. Should Respond

India’s Internal Challenges to Global Leadership

No More Free Rides in a Transactional World