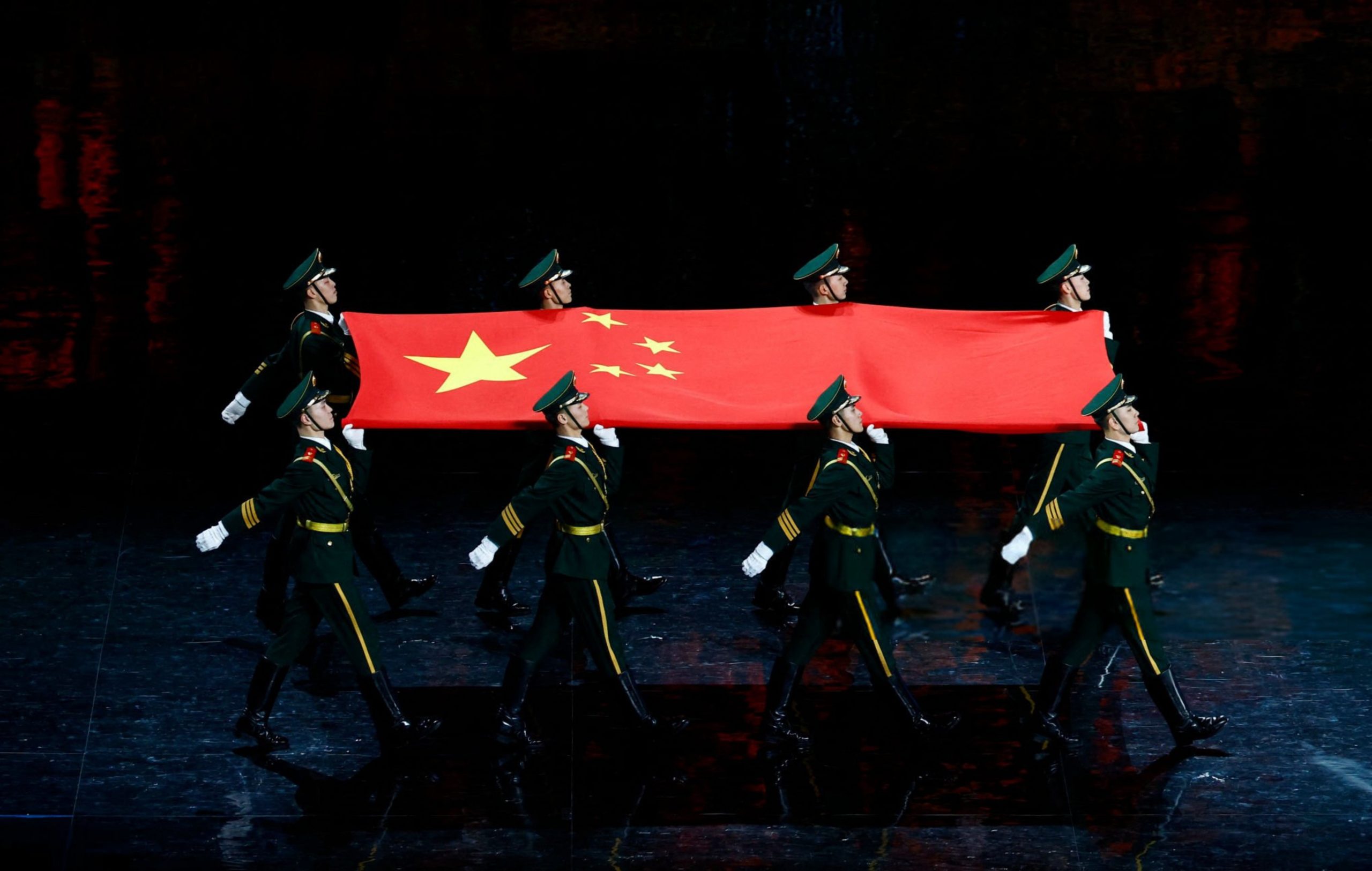

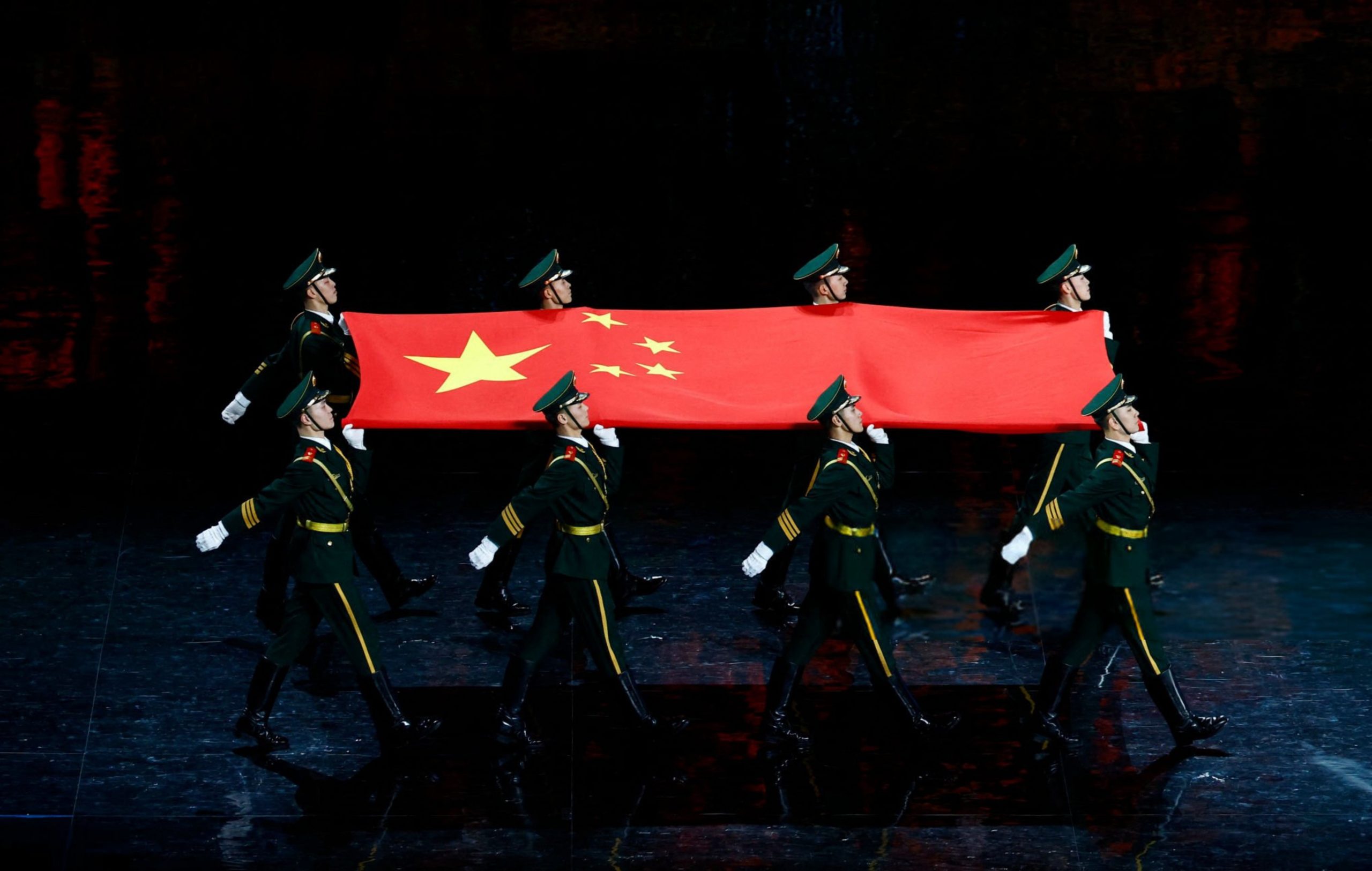

Members of the Chinese military carry China's national flag during the opening ceremony of the Harbin 2025 Asian Winter Games in Harbin, northeast China's Heilongjiang province on February 7, 2025. (Photo by Issei Kato / POOL / AFP) (Photo by ISSEI KATO/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

Described often as a ‘miracle,’ China has consolidated itself as a global power following four decades of substantial growth and development. Accompanying China’s rising political-economic significance is the increase in its global, and more notably regional, influence. From the creation of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013 to the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2016, from its close trading ties with Southeast Asian countries to the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with ASEAN, China has increasingly been identified as an influential figure in Southeast Asia (SEA) – the region that China once exerted strong control over during historical times. The growing significance of China in SEA has been an important strategic concern of the United States, as it has been increasingly suspected amidst China’s rising regional influence that it may eventually undermine the global leadership of the U.S. by creating its own sphere of influence in Asia and transforming the global order back into a Cold War-styled bipolar age.

China’s Advantages in SEA

Cultural-historical and geographic factors provide convenient preconditions for China to exert influence in SEA and can, to a considerable extent, be regarded as innate advantages for China in influencing SEA today. China’s historical ties to SEA date back centuries and can be traced back to the tributary system of the Ming and Qing dynasties, which formalized China’s political suzerainty as well as trade privileges in the region. This long history of interaction and exchange has left a deep cultural imprint, fostering a sense of familiarity that China leverages today. Chinese immigrants in the region have further deepened the endurance of these historical and cultural ties. Large Chinese communities in SEA countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Singapore—many of whom arrived during the 19th and 20th centuries—have played pivotal roles in local communities.

The continued presence of China’s legacy in SEA has created a network of cultural ties that Beijing strategically engages with through language promotion and Confucian values. For instance, China’s outreach to the Peranakan Chinese communities in Malaysia and Indonesia, who maintain strong cultural and linguistic ties to China, provides an important soft power channel for Beijing to deepen bilateral relations. Furthermore, the heritage of Confucian values has allowed Confucius Institutes, a strong channel of Chinese cultural and language promotion, to flourish in SEA, providing Beijing with another strategic gateway to directly influence local communities. The legacy of these cultural-historical connections ensures that China’s engagement in the region is retained with a certain level of familiarity and connectivity and is not viewed as entirely ‘foreign,’ which grants China an advantage in crafting its influence in the region.

Besides cultural-historical legacies, China’s geographic closeness to SEA has also created a natural economic interdependence, reinforcing its influence through trade and tourism. The geographical positioning of SEA—lying almost directly south of mainland China, with extensive land and maritime connectivity—has facilitated extensive economic integration. For instance, China is ASEAN’s largest trading partner, with a trade amount totaling $911.7 billion in 2023, allowing it to exert a strong influence over SEA countries’ trade and economies. China’s control over critical supply chains—particularly in manufacturing, electronics, and agriculture—has made Southeast Asian economies deeply reliant on Chinese imports.

Described often as a ‘miracle,’ China has consolidated itself as a global power following four decades of substantial growth and development. Accompanying China’s rising political-economic significance is the increase in its global, and more notably regional, influence. From the creation of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013 to the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2016, from its close trading ties with Southeast Asian countries to the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with ASEAN, China has increasingly been identified as an influential figure in Southeast Asia (SEA) – the region that China once exerted strong control over during historical times. The growing significance of China in SEA has been an important strategic concern of the United States, as it has been increasingly suspected amidst China’s rising regional influence that it may eventually undermine the global leadership of the U.S. by creating its own sphere of influence in Asia and transforming the global order back into a Cold War-styled bipolar age.

China’s Advantages in SEA

Cultural-historical and geographic factors provide convenient preconditions for China to exert influence in SEA and can, to a considerable extent, be regarded as innate advantages for China in influencing SEA today. China’s historical ties to SEA date back centuries and can be traced back to the tributary system of the Ming and Qing dynasties, which formalized China’s political suzerainty as well as trade privileges in the region. This long history of interaction and exchange has left a deep cultural imprint, fostering a sense of familiarity that China leverages today. Chinese immigrants in the region have further deepened the endurance of these historical and cultural ties. Large Chinese communities in SEA countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Singapore—many of whom arrived during the 19th and 20th centuries—have played pivotal roles in local communities.

The continued presence of China’s legacy in SEA has created a network of cultural ties that Beijing strategically engages with through language promotion and Confucian values. For instance, China’s outreach to the Peranakan Chinese communities in Malaysia and Indonesia, who maintain strong cultural and linguistic ties to China, provides an important soft power channel for Beijing to deepen bilateral relations. Furthermore, the heritage of Confucian values has allowed Confucius Institutes, a strong channel of Chinese cultural and language promotion, to flourish in SEA, providing Beijing with another strategic gateway to directly influence local communities. The legacy of these cultural-historical connections ensures that China’s engagement in the region is retained with a certain level of familiarity and connectivity and is not viewed as entirely ‘foreign,’ which grants China an advantage in crafting its influence in the region.

Besides cultural-historical legacies, China’s geographic closeness to SEA has also created a natural economic interdependence, reinforcing its influence through trade and tourism. The geographical positioning of SEA—lying almost directly south of mainland China, with extensive land and maritime connectivity—has facilitated extensive economic integration. For instance, China is ASEAN’s largest trading partner, with a trade amount totaling $911.7 billion in 2023, allowing it to exert a strong influence over SEA countries’ trade and economies. China’s control over critical supply chains—particularly in manufacturing, electronics, and agriculture—has made Southeast Asian economies deeply reliant on Chinese imports.

Countries like Vietnam, while increasingly diversifying, remain tied to China for raw materials and components essential to their export-driven industries. Moreover, short travel distances and the resulting low costs have made SEA among the top destinations for Chinese tourists, who became the largest source of tourism income in the region. This tourism dependency gives China additional leverage, as China may restrict outbound tourism to pressure regional governments on political issues. This economic entanglement of trade and tourism, facilitated by geographic proximity, gives China structural leverage to shape policies and economic choices across SEA.

A ‘Carrot and Stick’ Approach

Besides utilizing the innate advantages of cultural-historical legacies and geographical proximity, what marks China’s more active engagement with SEA is its strategy of a ‘carrot and stick’ approach. China’s ‘carrot’ can most distinctly be understood as a deliberate strategy of economic incentives that reinforce Beijing’s influence through economic, especially infrastructural, investment. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), established in 2013, and later the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), established in 2016, provide the essential platforms for this approach.

The BRI, for instance, channeled investment into major infrastructural projects, including the China-Laos Railway, Malaysia’s East Coast Rail Link, and Indonesia’s high-speed railway connecting Jakarta to Bandung. The AIIB provides loans to support infrastructural development in SEA and beyond, with projects in SEA covering regional actors such as Indonesia, Cambodia, Laos, and the Philippines. These projects embed China at the centre of SEA’s economic development, establishing China’s identity as a supporter of regional growth, development, and prosperity, thereby providing China with an important channel of soft power to enhance its influence.

The scale and effects of investments, as the ‘carrot’ of China, have been accelerated following China’s increasing investment in an innovation outlook. Innovation initiatives, most notably the ‘Made in China 2025’ framework announced in 2015 and the ‘Innovation-driven Development Strategy’ published in 2016, have characterized China’s rapid technological rise in the past few years, gradually making China a comprehensive economic powerhouse with global significance in both the traditional manufacturing sector as well as the innovative high-tech sector. These developments in China’s technological capability have enabled it to invest in projects beyond traditional infrastructure and instead promote advanced infrastructural projects such as digital infrastructure and green technology. For instance, China has been instrumental in constructing solar farms and hydroelectric plants in countries like Cambodia and Laos, enhancing their energy security while further integrating them into China-led economic structures.

Countries like Vietnam, while increasingly diversifying, remain tied to China for raw materials and components essential to their export-driven industries. Moreover, short travel distances and the resulting low costs have made SEA among the top destinations for Chinese tourists, who became the largest source of tourism income in the region. This tourism dependency gives China additional leverage, as China may restrict outbound tourism to pressure regional governments on political issues. This economic entanglement of trade and tourism, facilitated by geographic proximity, gives China structural leverage to shape policies and economic choices across SEA.

A ‘Carrot and Stick’ Approach

Besides utilizing the innate advantages of cultural-historical legacies and geographical proximity, what marks China’s more active engagement with SEA is its strategy of a ‘carrot and stick’ approach. China’s ‘carrot’ can most distinctly be understood as a deliberate strategy of economic incentives that reinforce Beijing’s influence through economic, especially infrastructural, investment. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), established in 2013, and later the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), established in 2016, provide the essential platforms for this approach.

The BRI, for instance, channeled investment into major infrastructural projects, including the China-Laos Railway, Malaysia’s East Coast Rail Link, and Indonesia’s high-speed railway connecting Jakarta to Bandung. The AIIB provides loans to support infrastructural development in SEA and beyond, with projects in SEA covering regional actors such as Indonesia, Cambodia, Laos, and the Philippines. These projects embed China at the centre of SEA’s economic development, establishing China’s identity as a supporter of regional growth, development, and prosperity, thereby providing China with an important channel of soft power to enhance its influence.

The scale and effects of investments, as the ‘carrot’ of China, have been accelerated following China’s increasing investment in an innovation outlook. Innovation initiatives, most notably the ‘Made in China 2025’ framework announced in 2015 and the ‘Innovation-driven Development Strategy’ published in 2016, have characterized China’s rapid technological rise in the past few years, gradually making China a comprehensive economic powerhouse with global significance in both the traditional manufacturing sector as well as the innovative high-tech sector. These developments in China’s technological capability have enabled it to invest in projects beyond traditional infrastructure and instead promote advanced infrastructural projects such as digital infrastructure and green technology. For instance, China has been instrumental in constructing solar farms and hydroelectric plants in countries like Cambodia and Laos, enhancing their energy security while further integrating them into China-led economic structures.

While economic incentives encourage cooperation, China has also adopted coercive tactics, or the ‘stick,’ to assert its dominance in SEA, particularly in the South China Sea. Through a combination of military buildup, paramilitary activities, economic coercion, and territorial claims, Beijing enforces its coercive presence in the region to push for greater recognition and influence. One of the most aggressive tools in this approach is the expansion of China’s maritime forces, including the navy and the coast guard. The China Coast Guard is now the world’s largest coast guard force, which regularly conducts patrols and interferes with the activities of SEA nations in disputed waters. It frequently engages in confrontations with Philippine and Vietnamese vessels, using tactics such as blocking supply routes, water cannon attacks, and ramming fishing boats. This aggressive maritime strategy has intensified under China’s new Coast Guard Law, published in 2021, which authorizes the use of paramilitary force in what Beijing considers its territorial waters.

China’s willingness to consolidate control through hard power is further exemplified by its island-building campaign in the South China Sea. Over the past decade, Beijing has transformed reefs and atolls into militarized artificial islands, equipped with runways capable of deploying fighter jets, missile systems, and naval facilities. These installations have effectively extended China’s reach into waters claimed by the Philippines and Vietnam and further enhanced the threat of military action. Despite a 2016 ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) that invalidated China’s expansive claims under the Nine-Dash Line, Beijing has refused to acknowledge the decision, showcasing its confidence and determination in exerting control over the region.

China has also noticeably employed economic coercion to ‘punish’ countries that fail to recognize or comply with its influence. For example, when the Philippines filed a case against China over territorial disputes at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, China reacted by imposing stricter health checks on Philippine bananas and eventually imposed a full import ban on bananas and pineapples from the Philippines. While military and paramilitary coercion presents SEA actors with a probable threat, economic coercion imposes direct and real-time costs on their economies, creating a powerful combination that pushes SEA actors to yield to China’s influence.

China’s ‘carrot and stick’ strategy in SEA is a calculated blend of economic incentives and coercive pressure that jointly reinforces its dominance in the region. By waving the ‘carrot,’ Beijing has associated its presence with growth, development, and prosperity, building trust, recognition, and dependence among SEA actors. Yet, simultaneously, military assertiveness, maritime expansion, and economic coercion have been used to bend resisting actors and further solidify control. The combined use of the ‘carrot’ and the ‘stick’ has made SEA countries, either out of the pursuit of economic interests or the fear of bearing costs, comply—at least to some extent—with China’s regional interests, thereby allowing China to establish its relative influence in SEA.

Weaknesses of China’s influence

Despite its inherent advantages and active engagement, China’s influence in SEA is far from predominant. The weaknesses of China’s influence in SEA can be analyzed across three dimensions: the negative externalities of coercive approaches, the prevailing influence of the U.S., and the dependence of economic engagement and investment on China’s domestic economic performance. As an important part of China’s ‘carrot and stick’ strategy in SEA, coercive measures, as discussed above, have characterized a significant portion of China’s actions in the region. Yet, although coercion may somewhat contribute, in theory, to China’s influence, coercion and the use of force have nevertheless created negative externalities that have backfired on China. The Philippines and Vietnam are the most notable cases that illustrate the negative consequences of Beijing’s coercive actions.

The China Coast Guard is now the world’s largest coast guard force, which regularly conducts patrols and interferes with the activities of SEA nations in disputed waters.

While economic incentives encourage cooperation, China has also adopted coercive tactics, or the ‘stick,’ to assert its dominance in SEA, particularly in the South China Sea. Through a combination of military buildup, paramilitary activities, economic coercion, and territorial claims, Beijing enforces its coercive presence in the region to push for greater recognition and influence. One of the most aggressive tools in this approach is the expansion of China’s maritime forces, including the navy and the coast guard. The China Coast Guard is now the world’s largest coast guard force, which regularly conducts patrols and interferes with the activities of SEA nations in disputed waters. It frequently engages in confrontations with Philippine and Vietnamese vessels, using tactics such as blocking supply routes, water cannon attacks, and ramming fishing boats. This aggressive maritime strategy has intensified under China’s new Coast Guard Law, published in 2021, which authorizes the use of paramilitary force in what Beijing considers its territorial waters.

China’s willingness to consolidate control through hard power is further exemplified by its island-building campaign in the South China Sea. Over the past decade, Beijing has transformed reefs and atolls into militarized artificial islands, equipped with runways capable of deploying fighter jets, missile systems, and naval facilities. These installations have effectively extended China’s reach into waters claimed by the Philippines and Vietnam and further enhanced the threat of military action. Despite a 2016 ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) that invalidated China’s expansive claims under the Nine-Dash Line, Beijing has refused to acknowledge the decision, showcasing its confidence and determination in exerting control over the region.

China has also noticeably employed economic coercion to ‘punish’ countries that fail to recognize or comply with its influence. For example, when the Philippines filed a case against China over territorial disputes at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, China reacted by imposing stricter health checks on Philippine bananas and eventually imposed a full import ban on bananas and pineapples from the Philippines. While military and paramilitary coercion presents SEA actors with a probable threat, economic coercion imposes direct and real-time costs on their economies, creating a powerful combination that pushes SEA actors to yield to China’s influence.

China’s ‘carrot and stick’ strategy in SEA is a calculated blend of economic incentives and coercive pressure that jointly reinforces its dominance in the region. By waving the ‘carrot,’ Beijing has associated its presence with growth, development, and prosperity, building trust, recognition, and dependence among SEA actors. Yet, simultaneously, military assertiveness, maritime expansion, and economic coercion have been used to bend resisting actors and further solidify control. The combined use of the ‘carrot’ and the ‘stick’ has made SEA countries, either out of the pursuit of economic interests or the fear of bearing costs, comply—at least to some extent—with China’s regional interests, thereby allowing China to establish its relative influence in SEA.

Weaknesses of China’s influence

Despite its inherent advantages and active engagement, China’s influence in SEA is far from predominant. The weaknesses of China’s influence in SEA can be analyzed across three dimensions: the negative externalities of coercive approaches, the prevailing influence of the U.S., and the dependence of economic engagement and investment on China’s domestic economic performance. As an important part of China’s ‘carrot and stick’ strategy in SEA, coercive measures, as discussed above, have characterized a significant portion of China’s actions in the region. Yet, although coercion may somewhat contribute, in theory, to China’s influence, coercion and the use of force have nevertheless created negative externalities that have backfired on China. The Philippines and Vietnam are the most notable cases that illustrate the negative consequences of Beijing’s coercive actions.

The aggressive use of the Coast Guard against these countries, including blocking fishing vessels, harassing energy exploration activities, and constructing artificial islands, has fueled anti-China sentiment across the region. In the Philippines, public discontent over China’s coercion has driven the government to strengthen defense ties with the U.S., granting American forces expanded access to military bases under the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA). Vietnam, despite its economic reliance on China, has also ramped up security cooperation with Japan, India, and the U.S. as a counterbalance to Beijing’s assertiveness.

These consequences have not only limited the effectiveness of China’s coercive actions but have also restricted China’s ability to convert economic influence into full political alignment, making Southeast Asian nations wary of overdependence on Beijing. While China’s ‘carrot and stick’ approach is struggling with its repercussions, further challenges to China’s regional influence exist as most regional states continue to pursue a strategy of hedging—that is, engaging with both China and the U.S. rather than aligning exclusively with either power to maintain strategic flexibility. The U.S. retains a strong military presence in the region, with defense alliances in the Philippines and Thailand, and strategic partnerships with Singapore, Vietnam, and Indonesia.

The U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy, reinforced by initiatives such as the AUKUS security pact and the Quad alliance, offers SEA nations a viable security framework that prevents Beijing from gaining unchecked influence. Besides competition from the U.S. alone, Japan, South Korea, and the European Union are also expanding their investments in the region, giving SEA countries additional options beyond Chinese capital. The result is a fragmented geopolitical landscape where no single power holds undisputed influence, undermining Beijing’s ability to dictate regional affairs unilaterally. Last, but not least, China’s economic influence in SEA is largely reliant on its domestic economic performance, where recent signs of slowdown create the potential of a weakening Chinese ability to sustain large-scale investment projects.

Broke out mainly since the Covid-19 Pandemic, China’s economy now faces mounting challenges, including declining GDP growth, a crisis in the real estate sector, rising debt, and demographic decline, which could constrain future spending on regional investment, for instance, BRI or AIIB projects. Already, several high-profile infrastructure investment plans in SEA have faced delays, cost overruns, and funding dry-ups due to plunging Chinese capital. For instance, the Funan Techo Canal of Cambodia, a strategic infrastructure project that has an estimated cost of $1.7 billion, was initially designed to source 49% of its funds from Chinese capital. However, as Beijing is drastically downsizing its overseas investments due to the slowdown of its domestic economy, a clear commitment to funding from China has yet to arrive, putting the entire project in jeopardy. If China’s economic slowdown continues, its ability to offer large-scale infrastructure investments, concessional loans, and technological partnerships may diminish, reducing its leverage in SEA.

Though China has made significant inroads into SEA, its influence remains constrained by territorial conflicts, regional hedging strategies, competition from other actors, and domestic economic vulnerabilities. Negative public perceptions fueled by the ‘stick’ approach have undermined Beijing’s ability to translate economic engagement into political loyalty. Meanwhile, SEA countries continue to diversify their partnerships, leveraging both China’s economic opportunities and the U.S.’s security guarantees to avoid dependence on a single power. Additionally, as China faces an economic slowdown, its ability to sustain large-scale investment projects in SEA may weaken, further limiting its ability to consolidate regional influence while opening the door for competing powers to expand their influence. In this complex geopolitical environment, Beijing’s challenge is not only to maintain its existing economic ties but also to overcome regional distrust and strategic resistance, a task that remains far from guaranteed.

Opportunities for the U.S.

The weaknesses of China’s regional influence essentially imply opportunities for China’s major regional rival, the U.S., to leverage. First and most straightforwardly, China’s territorial disputes with SEA nations provide a strategic opening for the U.S. to deepen its engagement in the region. As China continues its maritime assertiveness, SEA nations increasingly seek external security partnerships to hedge against Beijing’s aggression. The U.S. has already reinforced its defense ties with the Philippines, expanding the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) to grant American forces access to key bases near the contested waters.

Similarly, Washington’s military drills with Vietnam, Indonesia, and Singapore signal its commitment to regional security. To maximize its influence, the U.S. could further institutionalize its security commitments through initiatives like a formalized Indo-Pacific maritime security pact or an expanded AUKUS framework that includes SEA partners. By aligning with regional actors that share discontent over Chinese expansionism, the U.S. can position itself as the principal security provider, undermining Beijing’s attempts to coerce its neighbors into strategic dependence. Beyond military engagement, the U.S. retains a dominant position in the global normative order, which it can use to rally SEA nations into an ideologically bonded coalition against China.

Washington can capitalize on its influence over institutions like the United Nations, World Bank, and IMF to reinforce liberal democratic norms and mobilize condemnation against China’s coercive tactics in the region. The U.S. Department of State and its allies have already amplified narratives on China’s debt-trap diplomacy, particularly in countries like Laos and Malaysia, where over-reliance on BRI funding has raised concerns over sovereignty erosion. To further erode China’s legitimacy, the U.S. can expand diplomatic engagement with SEA nations and enhance support for regional dispute-resolution mechanisms such as the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP), ensuring China is framed as a disruptive force rather than a stabilizing partner. By reinforcing these ideological alignments, the U.S. can gradually cultivate an anti-China consensus, limiting Beijing’s ability to project soft power in the region.

For both the U.S. and China, the challenge lies not only in outmaneuvering each other but in winning the ‘hearts and minds’ as well as the long-term commitment of SEA, a task far more complicated than coercion or economic incentives alone.

Economics and trade-wise, while China maintains strong regional supply chain dominance, the U.S. can counterbalance this by leveraging its superior position in the global value chain (GVC), particularly in high-tech industries like semiconductors, AI, and advanced manufacturing. Despite its regional economic entrenchment, China still lags behind the U.S. in critical technological sectors, especially in chip design, software, and cutting-edge research and development (R&D). Washington can use this technological leverage to deepen economic engagement with SEA through initiatives that prioritize value creation rather than low-cost manufacturing.

Meanwhile, the U.S.’s CHIPS and Science Act, which aims to reduce reliance on China in semiconductor packaging and assembly, provides an opportunity to anchor key Southeast Asian economies in Washington’s technological orbit. Countries like Vietnam and Malaysia, both of which play crucial roles in global semiconductor assembly and packaging, could be incentivized to shift further into U.S.-aligned value chains. The U.S. could also expand research partnerships and tech investments in tech-advanced SEA actors such as Singapore, offering an alternative to China’s dominant role in digital infrastructure. If effectively implemented, this strategy could undermine China’s ability to dictate the technological future of the region, reinforcing SEA’s economic dependence on the U.S. rather than Beijing.

Finally, though the U.S. just went through a change in the presidency and thereby foreign policy orientation, it is likely that U.S. engagement in SEA under President Trump will be only a shift in tone but not in strategic objectives. Though Trump’s transactional approach to foreign policy, the ‘America First’ rhetoric that potentially reduces the U.S.’s commitments to regional security alliances and economic agreements, and his historical skepticism toward multilateral institutions could pose challenges to sustained diplomatic influence, his administration’s hardline stance on China—emphasized through trade wars, supply chain decoupling, and military posturing in the South China Sea—nevertheless serves the key strategic purpose of containing China.

A second Trump term may see an even stronger push for economic and technological disengagement from China, which could accelerate SEA’s integration into U.S.-led value chains. China’s expanding influence in SEA, in sum, is largely driven by historical-cultural, geographical, economic, and political factors, yet it is far from uncontested. While Beijing has effectively leveraged its geographic proximity, trade dominance, investment initiatives, and military assertiveness to deepen its regional foothold, the negative externalities of its coercive tactics, the competition from U.S. influence, and economic vulnerabilities at home have constrained its ability to fully dominate the region. SEA nations, recognizing both the opportunities and risks of engagement with China, continue to hedge their bets, balancing economic cooperation with Beijing while maintaining security and ideological partnerships with Washington.

For the United States, these strategic ambiguities present critical opportunities. By capitalizing on territorial disputes, strengthening its security commitments, reinforcing its technological and economic leadership, and amplifying regional distrust toward China, Washington can counter Beijing’s influence and safeguard its strategic foothold in SEA. The region’s growing importance in global supply chains, semiconductor production, and digital infrastructure makes it a key battleground in the broader U.S.-China competition. Ultimately, SEA is not a passive stage for great-power rivalry but an active agent in shaping its own future. The region’s ability to balance external pressures, diversify partnerships, and assert strategic autonomy will determine whether it remains a contested space or tilts decisively toward one power.For both the U.S. and China, the challenge lies not only in outmaneuvering each other but in winning the ‘hearts and minds’ as well as the long-term commitment of SEA, a task far more complicated than coercion or economic incentives alone.

The aggressive use of the Coast Guard against these countries, including blocking fishing vessels, harassing energy exploration activities, and constructing artificial islands, has fueled anti-China sentiment across the region. In the Philippines, public discontent over China’s coercion has driven the government to strengthen defense ties with the U.S., granting

American forces expanded access to military bases under the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA). Vietnam, despite its economic reliance on China, has also ramped up security cooperation with Japan, India, and the U.S. as a counterbalance to Beijing’s assertiveness.

These consequences have not only limited the effectiveness of China’s coercive actions but have also restricted China’s ability to convert economic influence into full political alignment, making Southeast Asian nations wary of overdependence on Beijing. While China’s ‘carrot and stick’ approach is struggling with its repercussions, further challenges to China’s regional influence exist as most regional states continue to pursue a strategy of hedging—that is, engaging with both China and the U.S. rather than aligning exclusively with either power to maintain strategic flexibility. The U.S. retains a strong military presence in the region, with defense alliances in the Philippines and Thailand, and strategic partnerships with Singapore, Vietnam, and Indonesia.

The U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy, reinforced by initiatives such as the AUKUS security pact and the Quad alliance, offers SEA nations a viable security framework that prevents Beijing from gaining unchecked influence. Besides competition from the U.S. alone, Japan, South Korea, and the European Union are also expanding their investments in the region, giving SEA countries additional options beyond Chinese capital. The result is a fragmented geopolitical landscape where no single power holds undisputed influence, undermining Beijing’s ability to dictate regional affairs unilaterally. Last, but not least, China’s economic influence in SEA is largely reliant on its domestic economic performance, where recent signs of slowdown create the potential of a weakening Chinese ability to sustain large-scale investment projects.

Broke out mainly since the Covid-19 Pandemic, China’s economy now faces mounting challenges, including declining GDP growth, a crisis in the real estate sector, rising debt, and demographic decline, which could constrain future spending on regional investment, for instance, BRI or AIIB projects. Already, several high-profile infrastructure investment plans in SEA have faced delays, cost overruns, and funding dry-ups due to plunging Chinese capital. For instance, the Funan Techo Canal of Cambodia, a strategic infrastructure project that has an estimated cost of $1.7 billion, was initially designed to source 49% of its funds from Chinese capital. However, as Beijing is drastically downsizing its overseas investments due to the slowdown of its domestic economy, a clear commitment to funding from China has yet to arrive, putting the entire project in jeopardy. If China’s economic slowdown continues, its ability to offer large-scale infrastructure investments, concessional loans, and technological partnerships may diminish, reducing its leverage in SEA.

Though China has made significant inroads into SEA, its influence remains constrained by territorial conflicts, regional hedging strategies, competition from other actors, and domestic economic vulnerabilities. Negative public perceptions fueled by the ‘stick’ approach have undermined Beijing’s ability to translate economic engagement into political loyalty. Meanwhile, SEA countries continue to diversify their partnerships, leveraging both China’s economic opportunities and the U.S.’s security guarantees to avoid dependence on a single power. Additionally, as China faces an economic slowdown, its ability to sustain large-scale investment projects in SEA may weaken, further limiting its ability to consolidate regional influence while opening the door for competing powers to expand their influence. In this complex geopolitical environment, Beijing’s challenge is not only to maintain its existing economic ties but also to overcome regional distrust and strategic resistance, a task that remains far from guaranteed.

Opportunities for the U.S.

The weaknesses of China’s regional influence essentially imply opportunities for China’s major regional rival, the U.S., to leverage. First and most straightforwardly, China’s territorial disputes with SEA nations provide a strategic opening for the U.S. to deepen its engagement in the region. As China continues its maritime assertiveness, SEA nations increasingly seek external security partnerships to hedge against Beijing’s aggression. The U.S. has already reinforced its defense ties with the Philippines, expanding the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) to grant American forces access to key bases near the contested waters.

Similarly, Washington’s military drills with Vietnam, Indonesia, and Singapore signal its commitment to regional security. To maximize its influence, the U.S. could further institutionalize its security commitments through initiatives like a formalized Indo-Pacific maritime security pact or an expanded AUKUS framework that includes SEA partners. By aligning with regional actors that share discontent over Chinese expansionism, the U.S. can position itself as the principal security provider, undermining Beijing’s attempts to coerce its neighbors into strategic dependence. Beyond military engagement, the U.S. retains a dominant position in the global normative order, which it can use to rally SEA nations into an ideologically bonded coalition against China.

Washington can capitalize on its influence over institutions like the United Nations, World Bank, and IMF to reinforce liberal democratic norms and mobilize condemnation against China’s coercive tactics in the region. The U.S. Department of State and its allies have already amplified narratives on China’s debt-trap diplomacy, particularly in countries like Laos and Malaysia, where over-reliance on BRI funding has raised concerns over sovereignty erosion. To further erode China’s legitimacy, the U.S. can expand diplomatic engagement with SEA nations and enhance support for regional dispute-resolution mechanisms such as the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP), ensuring China is framed as a disruptive force rather than a stabilizing partner. By reinforcing these ideological alignments, the U.S. can gradually cultivate an anti-China consensus, limiting Beijing’s ability to project soft power in the region.

Economics and trade-wise, while China maintains strong regional supply chain dominance, the U.S. can counterbalance this by leveraging its superior position in the global value chain (GVC), particularly in high-tech industries like semiconductors, AI, and advanced manufacturing. Despite its regional economic entrenchment, China still lags behind the U.S. in critical technological sectors, especially in chip design, software, and cutting-edge research and development

(R&D). Washington can use this technological leverage to deepen economic engagement with SEA through initiatives that prioritize value creation rather than low-cost manufacturing.

Meanwhile, the U.S.’s CHIPS and Science Act, which aims to reduce reliance on China in semiconductor packaging and assembly, provides an opportunity to anchor key Southeast Asian economies in Washington’s technological orbit. Countries like Vietnam and Malaysia, both of which play crucial roles in global semiconductor assembly and packaging, could be incentivized to shift further into U.S.-aligned value chains. The U.S. could also expand research partnerships and tech investments in tech-advanced SEA actors such as Singapore, offering an alternative to China’s dominant role in digital infrastructure. If effectively implemented, this strategy could undermine China’s ability to dictate the technological future of the region, reinforcing SEA’s economic dependence on the U.S. rather than Beijing.

Finally, though the U.S. just went through a change in the presidency and thereby foreign policy orientation, it is likely that U.S. engagement in SEA under President Trump will be only a shift in tone but not in strategic objectives. Though Trump’s transactional approach to foreign policy, the ‘America First’ rhetoric that potentially reduces the U.S.’s commitments to regional security alliances and economic agreements, and his historical skepticism toward multilateral institutions could pose challenges to sustained diplomatic influence, his administration’s hardline stance on China—emphasized through trade wars, supply chain decoupling, and military posturing in the South China Sea—nevertheless serves the key strategic purpose of containing China.

A second Trump term may see an even stronger push for economic and technological disengagement from China, which could accelerate SEA’s integration into U.S.-led value chains. China’s expanding influence in SEA, in sum, is largely driven by historical-cultural, geographical, economic, and political factors, yet it is far from uncontested. While Beijing has effectively leveraged its geographic proximity, trade dominance, investment initiatives, and military assertiveness to deepen its regional foothold, the negative externalities of its coercive tactics, the competition from U.S. influence, and economic vulnerabilities at home have constrained its ability to fully dominate the region. SEA nations, recognizing both the opportunities and risks of engagement with China, continue to hedge their bets, balancing economic cooperation with Beijing while maintaining security and ideological partnerships with Washington.

For the United States, these strategic ambiguities present critical opportunities. By capitalizing on territorial disputes, strengthening its security commitments, reinforcing its technological and economic leadership, and amplifying regional distrust toward China, Washington can counter Beijing’s influence and safeguard its strategic foothold in SEA. The region’s growing importance in global supply chains, semiconductor production, and digital infrastructure makes it a key battleground in the broader U.S.-China competition. Ultimately, SEA is not a passive stage for great-power rivalry but an active agent in shaping its own future. The region’s ability to balance external pressures, diversify partnerships, and assert strategic autonomy will determine whether it remains a contested space or tilts decisively toward one power.For both the U.S. and China, the challenge lies not only in outmaneuvering each other but in winning the ‘hearts and minds’ as well as the long-term commitment of SEA, a task far more complicated than coercion or economic incentives alone.

Yizhou Miao is pursuing an MSc in International Political Economy at the London School of Economics. His expertise lies in China's rise, China-U.S. competition, and the China-U.S. 'Chip War'.