This illstration has been created by AI to use only in this article.

In the post-WWII era, the continent of Europe remained in a relatively stable state of peace and cohesion, much stronger than the centuries of war and conquest that preceded it. The creation of the European Union and its numerous bureaucratic institutions has allowed its member states to govern together harmoniously and democratically. That very structure and cohesion of all Europeans, whether they are E.U. member states or not, has grown much weaker in recent years due to a plethora of factors. The very idea of “Europeanness” is something that is intended to be all-encompassing of European countries, cultures, and citizens.

However, it is difficult for one of the most divided and diverse continents to come to a complete synopsis of what that idea looks like. Not only are there major geographical differences throughout Europe, but the societal norms and historical context vary greatly from country to country. The sheer fact that nearly every country in Europe has gone to war with one another demonstrates just how divided the continent is overall. While the political institutions and governments have formally forgiven each other, can the citizens ever get along? Does France not resent Germany for WWII? Will Ireland ever become friendly with the United Kingdom?

Additionally, is it possible for the citizens of each country to relate to their fellow Europeans? Aside from being European Union citizens, what do someone from Finland and someone from Malta have in common? Each of these questions has been revolving around Europe since the creation of the European Union. However, there are a few factors that have been used to hold Europeans together, such as economic cohesion and reliance on one another, and the fact that they have a common threat within Europe of Russia, and in some cases, Serbia (referred to as little Russia). Also, the establishment of democratic values and institutions since the fall of the monarchs that once ruled Europe, upholding the validity of Democratic Peace Theory, has established like-minded governments to work together.

However, these institutions and their values have grown weaker throughout Europe, and the world, with countries such as Türkiye, Hungary, and to a lesser extent Poland, demonstrating democratic backsliding during the 21st century. That being said, is it possible for Europe as a whole to have the shared identity it needs to be a global leader in the 21st century, or will the differences in people, ideology, alliances, economic status, and other causes force the continent to a status of division and gridlock?

The Limits of Unity

After the atrocities that occurred during World War II, the democratic powers of Europe understood that there was a need for unity across Europe and created the European Union in 1992 with the Maastricht Treaty, after a plethora of treaties that paved the way for the official union. The founding members of the E.U. that signed the treaty were Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. These nations knew there was a much-needed connection across the continent on a diplomatic, economic, and societal scale to ensure the events of WWII were never repeated.

is a M.A. at James Madison University, with a degree in European Union Policy Studies and a specialization in Foreign Security and Defense Policy.

In the post-WWII era, the continent of Europe remained in a relatively stable state of peace and cohesion, much stronger than the centuries of war and conquest that preceded it. The creation of the European Union and its numerous bureaucratic institutions has allowed its member states to govern together harmoniously and democratically. That very structure and cohesion of all Europeans, whether they are E.U. member states or not, has grown much weaker in recent years due to a plethora of factors. The very idea of “Europeanness” is something that is intended to be all-encompassing of European countries, cultures, and citizens.

However, it is difficult for one of the most divided and diverse continents to come to a complete synopsis of what that idea looks like. Not only are there major geographical differences throughout Europe, but the societal norms and historical context vary greatly from country to country. The sheer fact that nearly every country in Europe has gone to war with one another demonstrates just how divided the continent is overall. While the political institutions and governments have formally forgiven each other, can the citizens ever get along? Does France not resent Germany for WWII? Will Ireland ever become friendly with the United Kingdom?

Additionally, is it possible for the citizens of each country to relate to their fellow Europeans? Aside from being European Union citizens, what do someone from Finland and someone from Malta have in common? Each of these questions has been revolving around Europe since the creation of the European Union. However, there are a few factors that have been used to hold Europeans together, such as economic cohesion and reliance on one another, and the fact that they have a common threat within Europe of Russia, and in some cases, Serbia (referred to as little Russia). Also, the establishment of democratic values and institutions since the fall of the monarchs that once ruled Europe, upholding the validity of Democratic Peace Theory, has established like-minded governments to work together.

However, these institutions and their values have grown weaker throughout Europe, and the world, with countries such as Türkiye, Hungary, and to a lesser extent Poland, demonstrating democratic backsliding during the 21st century. That being said, is it possible for Europe as a whole to have the shared identity it needs to be a global leader in the 21st century, or will the differences in people, ideology, alliances, economic status, and other causes force the continent to a status of division and gridlock?

The Limits of Unity

After the atrocities that occurred during World War II, the democratic powers of Europe understood that there was a need for unity across Europe and created the European Union in 1992 with the Maastricht Treaty, after a plethora of treaties that paved the way for the official union. The founding members of the E.U. that signed the treaty were Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. These nations knew there was a much-needed connection across the continent on a diplomatic, economic, and societal scale to ensure the events of WWII were never repeated.

is a M.A. at James Madison University, with a degree in European Union Policy Studies and a specialization in Foreign Security and Defense Policy.

The E.U. was founded on the ideas of democracy, with the creation of its supranational branches of government with the European Parliament as the populous, the European Commission as the executive, the Council of the European Union as the representative legislature, and the Court of Justice of the European Union as the judicial. These entities, along with the other agencies within the E.U. bureaucracy, ensure that democratic values are upheld and human rights are established throughout all member states and are promoted in aspiring member states.

While the connection between European countries on a diplomatic level is vastly important, the need for economic continuity is equally vital to ensuring peace and prosperity throughout the continent. We saw this from the very beginning via the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC) through the Treaty of Rome in 1957. This establishment and its continuation have allowed continued harmony in the European economy and encouraged cross-border investment and trade, further aligning the countries’ interests. The main idea behind the EEC was the establishment of free movement among the entire community, with an emphasis on the free movement of goods, services, people, and capital.

This allows as much free trade as possible for the benefit of the European economy as a whole. One of the best examples of these ideals is the creation of the Schengen Area in Europe. With 29 total countries, including non-E.U. member states, the Schengen Area allows the free movement of people for both European Union citizens and tourists alike. Another aspect that has completely evolved the European economy and movement of capital is the creation of a common currency. The Euro was introduced as the common currency in Europe in January 1999 and currently has 19 E.U. member states that utilize the Euro, along with other non-E.U. countries. Countries such as Vatican City, Andorra, San Marino, and Monaco all have agreements with the E.U. to become part of the Eurozone.

However, in 2008, the Euro faced significant pressure and threats of failure due to Greece abusing loan practices from both the European Union and other foreign currency agents. Due to the massive amount of debt Greece had racked up, the Euro’s value took a significant hit and nearly fell as trust in the currency declined drastically. Eventually, the crisis was averted via the more established economies within the E.U., along with Greece, creating a bailout package that allowed Greece to bounce back. This crisis highlighted the need to hold more accountability and oversight within the Eurozone. A final example of the free movement that Europe believes in is the creation of the Erasmus program.

It is a foreign exchange student program that allows students from all over Europe to travel and study in different countries as a way to widen cultural knowledge and increase the understanding of how Europeans are different but share similar values. Yet while these institutions have fostered cooperation among governments, they have not necessarily fostered solidarity among peoples. The persistence of linguistic barriers, historical resentments, and regional disparities suggests that institutional integration has outpaced cultural integration.

The E.U. was founded on the ideas of democracy, with the creation of its supranational branches of government with the European Parliament as the populous, the European Commission as the executive, the Council of the European Union as the representative legislature, and the Court of Justice of the European Union as the judicial. These entities, along with the other agencies within the E.U. bureaucracy, ensure that democratic values are upheld and human rights are established throughout all member states and are promoted in aspiring member states.

While the connection between European countries on a diplomatic level is vastly important, the need for economic continuity is equally vital to ensuring peace and prosperity throughout the continent. We saw this from the very beginning via the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC) through the Treaty of Rome in 1957. This establishment and its continuation have allowed continued harmony in the European economy and encouraged cross-border investment and trade, further aligning the countries’ interests. The main idea behind the EEC was the establishment of free movement among the entire community, with an emphasis on the free movement of goods, services, people, and capital.

This allows as much free trade as possible for the benefit of the European economy as a whole. One of the best examples of these ideals is the creation of the Schengen Area in Europe. With 29 total countries, including non-E.U. member states, the Schengen Area allows the free movement of people for both European Union citizens and tourists alike. Another aspect that has completely evolved the European economy and movement of capital is the creation of a common currency. The Euro was introduced as the common currency in Europe in January 1999 and currently has 19 E.U. member states that utilize the Euro, along with other non-E.U. countries. Countries such as Vatican City, Andorra, San Marino, and Monaco all have agreements with the E.U. to become part of the Eurozone.

However, in 2008, the Euro faced significant pressure and threats of failure due to Greece abusing loan practices from both the European Union and other foreign currency agents. Due to the massive amount of debt Greece had racked up, the Euro’s value took a significant hit and nearly fell as trust in the currency declined drastically. Eventually, the crisis was averted via the more established economies within the E.U., along with Greece, creating a bailout package that allowed Greece to bounce back. This crisis highlighted the need to hold more accountability and oversight within the Eurozone. A final example of the free movement that Europe believes in is the creation of the Erasmus program.

It is a foreign exchange student program that allows students from all over Europe to travel and study in different countries as a way to widen cultural knowledge and increase the understanding of how Europeans are different but share similar values. Yet while these institutions have fostered cooperation among governments, they have not necessarily fostered solidarity among peoples. The persistence of linguistic barriers, historical resentments, and regional disparities suggests that institutional integration has outpaced cultural integration.

Despite the efforts and innovations that the European Union has established and upheld during its tenure, there are numerous underlying factors that it will likely never be able to escape. The most noticeable factor that remains a wedge in the concept of “Europeanness” is the significant language barrier between countries. At present, there are 24 languages that are recognized as official E.U. languages, with the original four in 1957 being Italian, German, Dutch, and French, and with the newest language being Croatian in 2013. While languages such as English, German, and French remain dominant in most of the original E.U. member states, there remains a significant disconnect from the lesser spoken languages, specifically those of less tenured member states and former members of the Iron Curtain.

The E.U. has attempted to instill multilingualism as a core principle of its cultural cohesion, but it remains a significant division between member states. Another challenge that the E.U. constantly faces is the underlying historical context of wars and predatory practices of former imperial powers and monarchical powers. The scars from both World Wars remain very prevalent throughout member states, especially when taking into account the volume of human rights abuses and vast destruction that took place across the continent. France and Germany remain rivals in just about everything.

There are extreme disconnects between Western Europe and former Eastern Bloc countries. The climate needs of the northern countries of Sweden and Finland vary drastically from those in the south, such as Italy, Spain, and Greece. Additionally, the finalization of Brexit removed a historically global actor in the United Kingdom from a majority of E.U.-focused diplomatic and policy decisions. Overall, there are numerous areas where the European Union can promote continuity and unity but must overcome the underlying cleavages that influence individual member state actions.

Who Belongs in Europe

The migration crisis has become a litmus test for the strength of European identity. The divergent responses among member states reveal not only policy disagreements but a deeper uncertainty about what it means to be European—and who belongs within that identity. Whether it is refugees from conflicts in Ukraine, individuals fleeing war and persecution from the Middle East, or climate refugees from all over Africa, each country in Europe has a different stance on how—and if—these migrants should be accepted. Typically, countries that have strong economic infrastructures and more influence within the European Union tend to be more accepting of these migrants and have an open-arm policy stance, in a general sense.

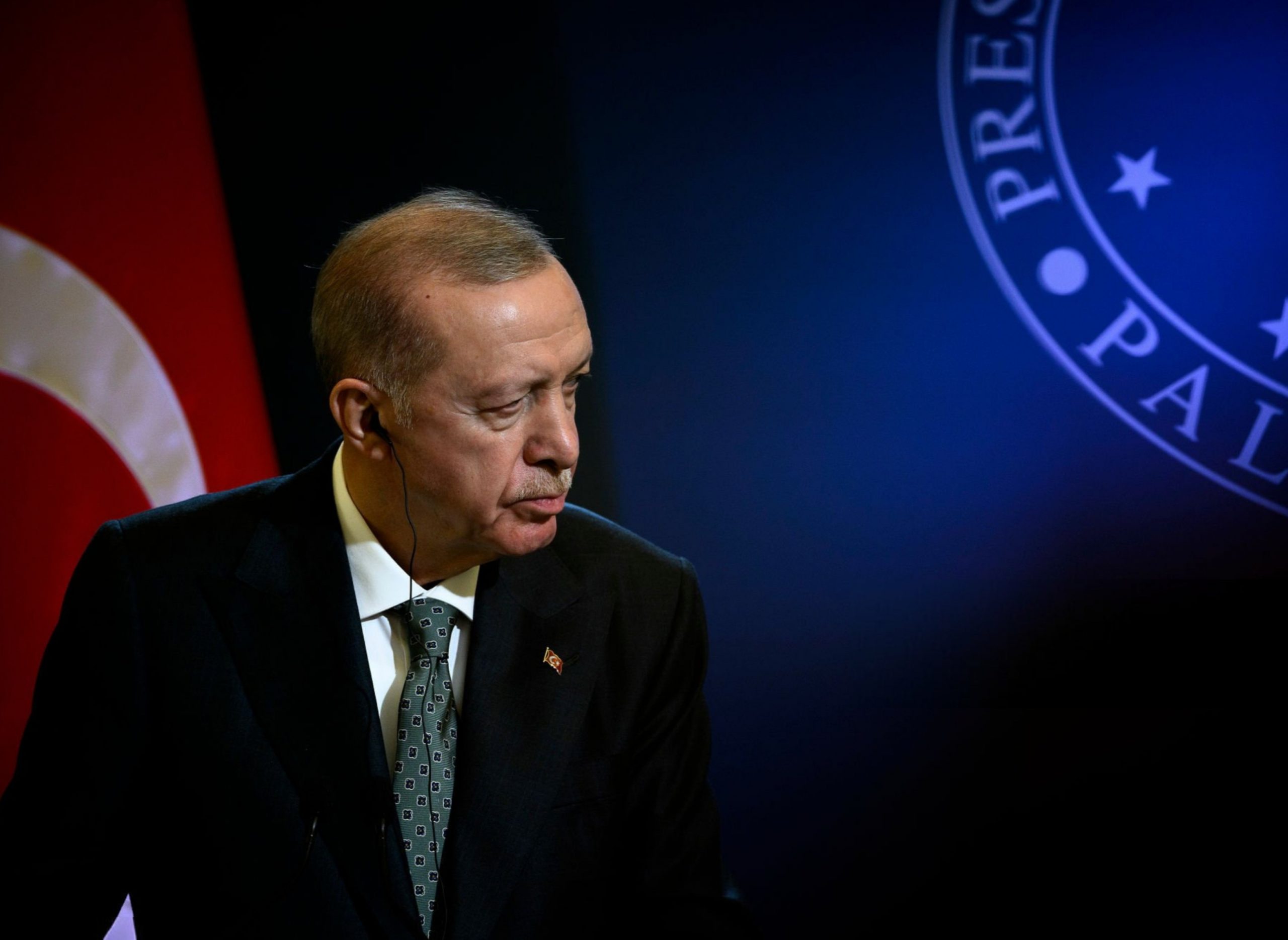

For example, Germany has been the most vocal and accepting of refugees throughout the European Union, especially for those migrating from the conflicts and hardships in the Middle East. When Angela Merkel (Chancellor of Germany) created the open border policy for refugees from the Middle East in 2015, the number of individuals accepted by Germany increased from roughly 890,000 in 2016 to just over 3 million in 2024. Germany was also the leader in the E.U.-Türkiye refugee deal. This deal, at brass tacks, was designed to move Syrian refugees from Greece to Türkiye, but to allow Syrian refugees within Türkiye already access to the E.U. This deal introduced the idea of a “safe third country” and designated Türkiye as said country.

The divergent responses among member states reveal not only policy disagreements but a deeper uncertainty about what it means to be European—and who belongs within that identity.

However, due to increased humanitarian issues within Türkiye, deriving from the consolidation of power by Türkiye’s President, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, E.U. academics and members from the E.U.’s judicial sector have called the deal “shameful” and criticize the executive branch of the E.U. for making such an ill-advised deal. Some argue that the haste and naivety within the creation of this deal has caused a massive humanitarian crisis within Türkiye, as well as forced refugees to remain in Greece under brutal living conditions. Germany has been the leader in migrant acceptance and continues to pursue an immigration policy that encourages Europe to accept more migrants.

Despite Germany, Europe’s largest economy, having an open border policy, this is not synonymous with all European Union member states, as Viktor Orbán and Hungary have been staunchly against accepting refugees, no matter where their origin is from. From the years 2012 to 2023, Hungary ranked last out of all European Union member states in terms of first-time asylum applicants and total positive decisions. With a positive decision ratio of 1.44%, Hungary accepts significantly fewer asylum-seekers than its fellow E.U. members, 22 of whom have rates of over 20%, with Estonia (94.55%) and Germany (54.40%) coming in as the two highest acceptance rates. The other countries that fall below the 20% mark are Slovenia (3.68%), Croatia (4.74%), Poland (16.34%), and Romania (17.47%).

While these numbers reflect the overall attitudes towards migration into the European Union, the member states that enact the policies differ based on the variety of areas from which migrants are fleeing toward Europe for assistance. This is especially true when applied to individuals migrating from Africa across the Mediterranean Sea. For instance, the European Union has made numerous efforts to open dialogues on immigration, establish relationships with African countries, and prevent various international criminal organizations from profiting from immigration. However, Giorgia Meloni, Prime Minister of Italy, has a very hard-line stance against illegal immigration.

Italy’s situation with Africa is vastly different than that of Germany, as they are immensely closer to the migration routes and have been dealing with the issue much longer. Meloni has been open to creating migration channels and economic relationships with various North African countries, such as Tunisia, but there remains a large undertone from Meloni and her party to “blockade” irregular and illegal migrants. If this far-right policy were to become enforced, the differences between Italian and German immigration policy would be immense and would likely be represented in the E.U.’s institutions.

The reasoning and rationale used for anti-immigration policy align directly with the increased far-right politics in the European Union, and the increased concentration of power allows these regimes to act swiftly with little opposition. There are three major “threats” that scholars and government officials use to justify anti-immigration sentiment: economic, cultural, and security. This is evident in Hungary and Poland, which we know are rather hesitant to allow non-E.U. citizens to migrate. These regimes use the fear of losing their culture to foreign nationals to justify disallowing migrants, especially when the migrants derive from the Middle East and Muslim countries.

In addition to fear of losing a nation’s culture, the security threats that legislators use highlight “potential terrorists,” with the underlying sentiment of Islamophobia. Additionally, if there are violent crimes that surface on social media or gain national attention, there is an immediate uptick in anti-migrant discussions throughout society and in government forums. While immigrants typically improve the economy of a certain country, some regimes use the cost of immigrants as a rationale for turning away migrants. This was seen in Austria from the Freedom Party of Austria, who claimed that additional migrants would cause too much economic strain.

Additionally, as seen in the United States and E.U. member states, employment competition is a large societal influence on attitudes toward immigrants. If there is a lack of national employment, governments can use migrants as an excuse, claiming that individuals are undercutting the natural citizens of the country. Immigration throughout the E.U. is very polarized, as each of the negative viewpoints is counteracted with a positive idea. For cultural threats, the opposite spin is increased cultural diversity. For security threats, the positive for immigration is giving individuals a path away from persecution and violence in their home country. For economic threat perceptions, the positive impacts of immigration include fulfilling the workforce and increasing the number of laborers, potentially in industries that the national population cannot meet, such as agriculture.

In response to the perceived erosion of European identity, a new form of symbolic boundary-making has emerged—what some call “cultural Christianity.” This is not a religious revival, but a political invocation of Christian heritage as a marker of belonging. Leaders like Viktor Orbán in Hungary and parties across Central Europe have framed Christianity as the civilizational core of Europe, using it to justify exclusionary policies on migration, gender, and education. While church attendance continues to decline across the continent, with the Christian share of Europe’s population dropping from 76% in 2010 to 67% in 2020, the language of Christian values has gained political traction. It functions less as a faith and more as a filter—distinguishing “native” Europeans from outsiders, particularly Muslims. This symbolic Christianity has become a cultural defense mechanism, invoked not to unify, but to draw lines.

One Europe, Many Fault Lines

Throughout the history of Europe, there have been significant geographical and regional divides across Europe. As the continent has evolved into a more unified state in the post-WWII era, some of these rivalries and differences remain politically significant. They remain influential dividing factors when it comes to unified E.U. positions in a plethora of areas. The differences between former Eastern Bloc countries and Western countries during the days of the Cold War remain largely impactful on the processes and ideologies of the European Union. Additionally, the economic disparity between Northern and Southern member states causes the E.U. to remain in a state of perpetuity and fear that the economic system they were founded on could crumble in an instant.

Looking at the East and West relationships within the E.U., it is without a doubt that the lasting impacts of the Soviet Union, merged with the current status of Russia, heavily influence E.U. operations in the modern day. While a majority of E.U. member states have a hard-line stance of supporting Ukraine in the Russian war of aggression, it is worth mentioning that not all member states feel the same way. The most notable pro-Russian member state is Hungary, as their Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, has been adamant about allowing Russia to remain as the E.U.’s major gas and oil provider and disapproves of the sanctions the Commission has placed on Russia.

Despite the efforts and innovations that the European Union has established and upheld during its tenure, there are numerous underlying factors that it will likely never be able to escape. The most noticeable factor that remains a wedge in the concept of “Europeanness” is the significant language barrier between countries. At present, there are 24 languages that are recognized as official E.U. languages, with the original four in 1957 being Italian, German, Dutch, and French, and with the newest language being Croatian in 2013. While languages such as English, German, and French remain dominant in most of the original E.U. member states, there remains a significant disconnect from the lesser spoken languages, specifically those of less tenured member states and former members of the Iron Curtain.

The E.U. has attempted to instill multilingualism as a core principle of its cultural cohesion, but it remains a significant division between member states. Another challenge that the E.U. constantly faces is the underlying historical context of wars and predatory practices of former imperial powers and monarchical powers. The scars from both World Wars remain very prevalent throughout member states, especially when taking into account the volume of human rights abuses and vast destruction that took place across the continent. France and Germany remain rivals in just about everything.

There are extreme disconnects between Western Europe and former Eastern Bloc countries. The climate needs of the northern countries of Sweden and Finland vary drastically from those in the south, such as Italy, Spain, and Greece. Additionally, the finalization of Brexit removed a historically global actor in the United Kingdom from a majority of E.U.-focused diplomatic and policy decisions. Overall, there are numerous areas where the European Union can promote continuity and unity but must overcome the underlying cleavages that influence individual member state actions.

Who Belongs in Europe

The migration crisis has become a litmus test for the strength of European identity. The divergent responses among member states reveal not only policy disagreements but a deeper uncertainty about what it means to be European—and who belongs within that identity. Whether it is refugees from conflicts in Ukraine, individuals fleeing war and persecution from the Middle East, or climate refugees from all over Africa, each country in Europe has a different stance on how—and if—these migrants should be accepted. Typically, countries that have strong economic infrastructures and more influence within the European Union tend to be more accepting of these migrants and have an open-arm policy stance, in a general sense.

For example, Germany has been the most vocal and accepting of refugees throughout the European Union, especially for those migrating from the conflicts and hardships in the Middle East. When Angela Merkel (Chancellor of Germany) created the open border policy for refugees from the Middle East in 2015, the number of individuals accepted by Germany increased from roughly 890,000 in 2016 to just over 3 million in 2024. Germany was also the leader in the E.U.-Türkiye refugee deal. This deal, at brass tacks, was designed to move Syrian refugees from Greece to Türkiye, but to allow Syrian refugees within Türkiye already access to the E.U. This deal introduced the idea of a “safe third country” and designated Türkiye as said country.

In addition to Hungary, Slovakia and Bulgaria continue to have pro-Russian sentiment in their political discourse. In both countries, the general population would prefer a Russian victory as opposed to a Ukrainian one. Also, non-E.U. member states that support Russia (Belarus and Serbia) place an immense amount of pressure on others in the region, as they would not support their neighbors if Russia were to invade and may harbor various Russian proxy groups. While Slovakia has increased its willingness to send arms and military equipment to assist Ukraine, Bulgaria and Hungary remain against any arms assistance for the duration of the conflict.

In addition to differences in addressing regional conflicts, the economic differences between the East and West of the European Union remain significant and can be traced back to the policies introduced after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Under the Marshall Plan, countries with more democratic institutions and capitalistic values were typically more rewarded when it came to post-war relief. This allowed countries like the former West Germany and France to flourish, but left those still under relative communist rule to be left behind, such as Poland. Their respective GDPs reflected this disparity, as those under the Iron Curtain failed to meet consumer needs and lacked resources to invite investment and create new industries. This phenomenon sprouted resentment among the Eastern countries and fueled anti-democratic values as the West grew immensely.

The liberal cosmopolitanism that once animated the European project is showing signs of fatigue. Once hailed as a model of post-national integration, the E.U. is now viewed by many as an elite-driven enterprise, disconnected from local realities. In cities like Berlin, Amsterdam, and Paris, cosmopolitan ideals still flourish—but outside the urban core, skepticism is growing. A 2016 Pew survey found that 59% of Europeans believed immigrants were a burden, and only 32% thought immigration had improved their countries. In Italy and Greece, those numbers were even starker. The backlash is not just about policy—it is cultural. Multiculturalism, once seen as a solution, is now blamed for fragmented societies and alienated citizenries. The dream of a borderless Europe has given way to a politics of protection, where identity is no longer shared but defended.

These regional divides are more than economic or strategic—they are cultural. The lingering distrust between East and West, and the resentment between North and South, continue to fracture any sense of collective European belonging. Traditionally, member states in the North were much more economically prosperous, while the countries in the South did not develop nearly as fast or efficiently. While the origins can be traced back to Protestantism and Christianity across Europe, the 2008 financial crisis, the 2015 migration crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how the relationship has played out in the modern era.

In 2008, the larger economies of the North refrained from bailing out the more financially fragile due to their riskier practices and immense debt. In 2015, Southern member states again felt left behind as Northern countries made open-border policies but refrained from hosting the mass influx of migrants. Also, in 2020, Southern member states were impacted severely and much sooner than their Northern counterparts. They required immediate assistance via “coronabonds,” and while the initial assistance was slow, the E.U. managed to act in a much swifter manner than during the previous two crises.

However, due to increased humanitarian issues within Türkiye, deriving from the consolidation of power by Türkiye’s President, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, E.U. academics and members from the E.U.’s judicial sector have called the deal “shameful” and criticize the executive branch of the E.U. for

making such an ill-advised deal. Some argue that the haste and naivety within the creation of this deal has caused a massive humanitarian crisis within Türkiye, as well as forced refugees to remain in Greece under brutal living conditions. Germany has been the leader in migrant acceptance and continues to pursue an immigration policy that encourages Europe to accept more migrants.

Despite Germany, Europe’s largest economy, having an open border policy, this is not synonymous with all European Union member states, as Viktor Orbán and Hungary have been staunchly against accepting refugees, no matter where their origin is from. From the years 2012 to 2023, Hungary ranked last out of all European Union member states in terms of first-time asylum applicants and total positive decisions. With a positive decision ratio of 1.44%, Hungary accepts significantly fewer asylum-seekers than its fellow E.U. members, 22 of whom have rates of over 20%, with Estonia (94.55%) and Germany (54.40%) coming in as the two highest acceptance rates. The other countries that fall below the 20% mark are Slovenia (3.68%), Croatia (4.74%), Poland (16.34%), and Romania (17.47%).

While these numbers reflect the overall attitudes towards migration into the European Union, the member states that enact the policies differ based on the variety of areas from which migrants are fleeing toward Europe for assistance. This is especially true when applied to individuals migrating from Africa across the Mediterranean Sea. For instance, the European Union has made numerous efforts to open dialogues on immigration, establish relationships with African countries, and prevent various international criminal organizations from profiting from immigration. However, Giorgia Meloni, Prime Minister of Italy, has a very hard-line stance against illegal immigration.

Italy’s situation with Africa is vastly different than that of Germany, as they are immensely closer to the migration routes and have been dealing with the issue much longer. Meloni has been open to creating migration channels and economic relationships with various North African countries, such as Tunisia, but there remains a large undertone from Meloni and her party to “blockade” irregular and illegal migrants. If this far-right policy were to become enforced, the differences between Italian and German immigration policy would be immense and would likely be represented in the E.U.’s institutions.

The reasoning and rationale used for anti-immigration policy align directly with the increased far-right politics in the European Union, and the increased concentration of power allows these regimes to act swiftly with little opposition. There are three major “threats” that scholars and government officials use to justify anti-immigration sentiment: economic, cultural, and security. This is evident in Hungary and Poland, which we know are rather hesitant to allow non-E.U. citizens to migrate. These regimes use the fear of losing their culture to foreign nationals to justify disallowing migrants, especially when the migrants derive from the Middle East and Muslim countries.

In addition to fear of losing a nation’s culture, the security threats that legislators use highlight “potential terrorists,” with the underlying sentiment of Islamophobia. Additionally, if there are violent crimes that surface on social media or gain national attention, there is an immediate uptick in anti-migrant discussions throughout society and in government forums. While immigrants typically improve the economy of a certain country, some regimes use the cost of immigrants as a rationale for turning away migrants. This was seen in Austria from the Freedom Party of Austria, who claimed that additional migrants would cause too much economic strain.

Additionally, as seen in the United States and E.U. member states, employment competition is a large societal influence on attitudes toward immigrants. If there is a lack of national employment, governments can use migrants as an excuse, claiming that individuals are undercutting the natural citizens of the country. Immigration throughout the E.U. is very polarized, as each of the negative viewpoints is counteracted with a positive idea. For cultural threats, the opposite spin is increased cultural diversity. For security threats, the positive for immigration is giving individuals a path away from persecution and violence in their home country. For economic threat perceptions, the positive impacts of immigration include fulfilling the workforce and increasing the number of laborers, potentially in industries that the national population cannot meet, such as agriculture.

In response to the perceived erosion of European identity, a new form of symbolic boundary-making has emerged—what some call “cultural Christianity.” This is not a religious revival, but a political invocation of Christian heritage as a marker of belonging. Leaders like Viktor Orbán in Hungary and parties across Central Europe have framed Christianity as the civilizational core of Europe, using it to justify exclusionary policies on migration, gender, and education. While church attendance continues to decline across the continent, with the Christian share of Europe’s population dropping from 76% in 2010 to 67% in 2020, the language of Christian values has gained political traction. It functions less as a faith and more as a filter—distinguishing “native” Europeans from outsiders, particularly Muslims. This symbolic Christianity has become a cultural defense mechanism, invoked not to unify, but to draw lines.

One Europe, Many Fault Lines

Throughout the history of Europe, there have been significant geographical and regional divides across Europe. As the continent has evolved into a more unified state in the post-WWII era, some of these rivalries and differences remain politically significant. They remain influential dividing factors when it comes to unified E.U. positions in a plethora of areas. The differences between former Eastern Bloc countries and Western countries during the days of the Cold War remain largely impactful on the processes and ideologies of the European Union. Additionally, the economic disparity between Northern and Southern member states causes the E.U. to remain in a state of perpetuity and fear that the economic system they were founded on could crumble in an instant.

Looking at the East and West relationships within the E.U., it is without a doubt that the lasting impacts of the Soviet Union, merged with the current status of Russia, heavily influence E.U. operations in the modern day. While a majority of E.U. member states have a hard-line stance of supporting Ukraine in the Russian war of aggression, it is worth mentioning that not all member states feel the same way. The most notable pro-Russian member state is Hungary, as their Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, has been adamant about allowing Russia to remain as the E.U.’s major gas and oil provider and disapproves of the sanctions the Commission has placed on Russia.

In addition to Hungary, Slovakia and Bulgaria continue to have pro-Russian sentiment in their political discourse. In both countries, the general population would prefer a Russian victory as opposed to a Ukrainian one. Also, non-E.U. member states that support Russia (Belarus and Serbia) place an immense amount of pressure on others in the region, as they would not support their neighbors if Russia were to invade and may harbor various Russian proxy groups. While Slovakia has increased its willingness to send arms and military equipment to assist Ukraine, Bulgaria and Hungary remain against any arms assistance for the duration of the conflict.

In addition to differences in addressing regional conflicts, the economic differences between the East and West of the European Union remain significant and can be traced back to the policies introduced after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Under the Marshall Plan, countries with more democratic institutions and capitalistic values were typically more rewarded when it came to post-war relief. This allowed countries like the former West Germany and France to flourish, but left those still under relative communist rule to be left behind, such as Poland. Their respective GDPs reflected this disparity, as those under the Iron Curtain failed to meet consumer needs and lacked resources to invite investment and create new industries. This phenomenon sprouted resentment among the Eastern countries and fueled anti-democratic values as the West grew immensely.

The liberal cosmopolitanism that once animated the European project is showing signs of fatigue. Once hailed as a model of post-national integration, the E.U. is now viewed by many as an elite-driven enterprise, disconnected from local realities. In cities like Berlin, Amsterdam, and Paris, cosmopolitan ideals still flourish—but outside the urban core, skepticism is growing. A 2016 Pew survey found that 59% of Europeans believed immigrants were a burden, and only 32% thought immigration had improved their countries. In Italy and Greece, those numbers were even starker. The backlash is not just about policy—it is cultural. Multiculturalism, once seen as a solution, is now blamed for fragmented societies and alienated citizenries. The dream of a borderless Europe has given way to a politics of protection, where identity is no longer shared but defended.

These regional divides are more than economic or strategic—they are cultural. The lingering distrust between East and West, and the resentment between North and South, continue to fracture any sense of collective European belonging. Traditionally, member states in the North were much more economically prosperous, while the countries in the South did not develop nearly as fast or efficiently. While the origins can be traced back to Protestantism and Christianity across Europe, the 2008 financial crisis, the 2015 migration crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how the relationship has played out in the modern era.

In 2008, the larger economies of the North refrained from bailing out the more financially fragile due to their riskier practices and immense debt. In 2015, Southern member states again felt left behind as Northern countries made open-border policies but refrained from hosting the mass influx of migrants. Also, in 2020, Southern member states were impacted severely and much sooner than their Northern counterparts. They required immediate assistance via “coronabonds,” and while the initial assistance was slow, the E.U. managed to act in a much swifter manner than during the previous two crises.

Beneath the surface of institutional continuity, the E.U. is confronting a deeper rupture: the erosion of liberal democratic norms within its own ranks. The consensus that once bound member states around the rule of law, separation of powers,

and individual rights is fracturing. In Hungary and Poland, illiberal democracies have taken root, consolidating executive power and undermining judicial independence. A 2025 study in European Political Science describes this as a “dissensus” over liberal democracy—no longer a fringe phenomenon, but a structural challenge. The E.U.’s internal cohesion is now threatened not only by external pressures, but by the normalization of authoritarian tendencies within. If shared norms no longer hold, can a shared identity survive?

The European Union has long stood as a symbol of postwar reconciliation, institutional innovation, and economic interdependence. Yet beneath the surface of treaties and trade lies a more elusive and fragile ambition: the cultivation of a shared European identity. While the E.U. has succeeded in creating a common market and a supranational legal order, it has not yet succeeded in forging a cultural consciousness that binds its citizens together beyond borders and bureaucracies. The fractures explored throughout this analysis—historical grievances, migration disputes, regional disparities, and democratic backsliding—are not merely policy disagreements. They are symptoms of a deeper identity crisis that continues to challenge the very foundation of the European project.

Despite decades of integration, the sense of “Europeanness” remains uneven and contested. In Western and Northern Europe, attachment to the E.U. is relatively strong, while in Southern and Eastern states, skepticism and ambivalence persist. In countries like Ireland and the Netherlands, over two-thirds of citizens express a strong connection to the Union, while in Greece and Bulgaria, fewer than half feel the same. These disparities reflect not only economic and political differences but also divergent historical experiences and cultural narratives. The legacy of the Iron Curtain, the uneven benefits of globalization, and the varied responses to migration have all contributed to a fragmented European identity. Yet the story is not one of inevitable decline. Among younger generations, particularly those who have participated in cross-border programs like Erasmus+, a more cohesive European identity is beginning to take shape.

Over 80 percent of Erasmus participants report feeling more European after their exchange, and many go on to form transnational networks that transcend national boundaries. These experiences, though limited in scale, suggest that identity can be cultivated through shared experiences, mobility, and education. Even among younger Europeans, identity formation is increasingly polarized. The divide is no longer just between East and West, but between cosmopolitan and communitarian worldviews. Digital platforms have amplified this cleavage, turning cultural debates into ideological battlegrounds. A 2021 study in European Journal of Futures Research warns that the postwar consensus—on democracy, on Europe itself—is unraveling. What was once a shared project is now a contested space, with competing visions of what Europe is and who it is for. In this environment, building a common identity requires more than shared programs—it demands shared meaning.

Some argue that the E.U.’s diversity is not a liability but a strength—that unity need not require uniformity. The idea of a layered identity, where individuals see themselves as both national and European citizens, offers a more realistic and resilient model for the future. Rather than erasing cultural differences, the E.U. can embrace them within a framework of shared democratic values and mutual respect. This vision aligns with the concept of constitutional patriotism, where allegiance is rooted not in ethnicity or language but in common principles and institutions. To move toward this vision, the E.U. must invest in the cultural and civic dimensions of integration with the same seriousness it has applied to economic and political union.

To realize a more cohesive European identity, the E.U. must commit to deepening its cultural and civic integration with the same resolve it has shown in advancing economic and political unity. This effort demands a strategic investment in initiatives that bridge the growing identity gap among member states. A continent-wide civic education program should be introduced to teach European history, democratic norms, and the responsibilities of E.U. citizenship—instilling a shared understanding of the Union’s purpose, particularly among younger generations.

In parallel, the Erasmus+ program ought to be significantly expanded to include not only university students but also vocational trainees, adult learners, and cultural workers, thereby making cross-border experiences more inclusive and widespread. Complementing these efforts, the establishment of pan-European media platforms—featuring multilingual news coverage and cultural content—would foster a common public sphere, counteract divisive nationalist narratives, and create space for democratic dialogue across borders.

The European Union was never meant to be merely a marketplace or a diplomatic forum. It was envisioned as a community of peoples, united not by sameness but by solidarity. If Europe is to lead in the 21st century, it must rediscover that ambition—not only in its policies, but in its identity. Without a shared sense of who Europeans are and what they stand for, the Union risks becoming a hollow structure, vulnerable to division and irrelevance. The future of Europe depends not only on what it builds, but on what it believes.

The dream of a borderless Europe has given way to a politics of protection, where identity is no longer shared but defended.

Beneath the surface of institutional continuity, the E.U. is confronting a deeper rupture: the erosion of liberal democratic norms within its own ranks. The consensus that once bound member states around the rule of law, separation of powers, and individual rights is fracturing. In Hungary and Poland, illiberal democracies have taken root, consolidating executive power and undermining judicial independence. A 2025 study in European Political Science describes this as a “dissensus” over liberal democracy—no longer a fringe phenomenon, but a structural challenge. The E.U.’s internal cohesion is now threatened not only by external pressures, but by the normalization of authoritarian tendencies within. If shared norms no longer hold, can a shared identity survive?

Can Identity Be Engineered?

The European Union has long stood as a symbol of postwar reconciliation, institutional innovation, and economic interdependence. Yet beneath the surface of treaties and trade lies a more elusive and fragile ambition: the cultivation of a shared European identity. While the E.U. has succeeded in creating a common market and a supranational legal order, it has not yet succeeded in forging a cultural consciousness that binds its citizens together beyond borders and bureaucracies. The fractures explored throughout this analysis—historical grievances, migration disputes, regional disparities, and democratic backsliding—are not merely policy disagreements. They are symptoms of a deeper identity crisis that continues to challenge the very foundation of the European project.

Despite decades of integration, the sense of “Europeanness” remains uneven and contested. In Western and Northern Europe, attachment to the E.U. is relatively strong, while in Southern and Eastern states, skepticism and ambivalence persist. In countries like Ireland and the Netherlands, over two-thirds of citizens express a strong connection to the Union, while in Greece and Bulgaria, fewer than half feel the same. These disparities reflect not only economic and political differences but also divergent historical experiences and cultural narratives. The legacy of the Iron Curtain, the uneven benefits of globalization, and the varied responses to migration have all contributed to a fragmented European identity. Yet the story is not one of inevitable decline. Among younger generations, particularly those who have participated in cross-border programs like Erasmus+, a more cohesive European identity is beginning to take shape.

Over 80 percent of Erasmus participants report feeling more European after their exchange, and many go on to form transnational networks that transcend national boundaries. These experiences, though limited in scale, suggest that identity can be cultivated through shared experiences, mobility, and education. Even among younger Europeans, identity formation is increasingly polarized. The divide is no longer just between East and West, but between cosmopolitan and communitarian worldviews. Digital platforms have amplified this cleavage, turning cultural debates into ideological battlegrounds. A 2021 study in European Journal of Futures Research warns that the postwar consensus—on democracy, on Europe itself—is unraveling. What was once a shared project is now a contested space, with competing visions of what Europe is and who it is for. In this environment, building a common identity requires more than shared programs—it demands shared meaning.

Some argue that the E.U.’s diversity is not a liability but a strength—that unity need not require uniformity. The idea of a layered identity, where individuals see themselves as both national and European citizens, offers a more realistic and resilient model for the future. Rather than erasing cultural differences, the E.U. can embrace them within a framework of shared democratic values and mutual respect. This vision aligns with the concept of constitutional patriotism, where allegiance is rooted not in ethnicity or language but in common principles and institutions. To move toward this vision, the E.U. must invest in the cultural and civic dimensions of integration with the same seriousness it has applied to economic and political union.

To realize a more cohesive European identity, the E.U. must commit to deepening its cultural and civic integration with the same resolve it has shown in advancing economic and political unity. This effort demands a strategic investment in initiatives that bridge the growing identity gap among member states. A continent-wide civic education program should be introduced to teach European history, democratic norms, and the responsibilities of E.U. citizenship—instilling a shared understanding of the Union’s purpose, particularly among younger generations.

In parallel, the Erasmus+ program ought to be significantly expanded to include not only university students but also vocational trainees, adult learners, and cultural workers, thereby making cross-border experiences more inclusive and widespread. Complementing these efforts, the establishment of pan-European media platforms—featuring multilingual news coverage and cultural content—would foster a common public sphere, counteract divisive nationalist narratives, and create space for democratic dialogue across borders.

The European Union was never meant to be merely a marketplace or a diplomatic forum. It was envisioned as a community of peoples, united not by sameness but by solidarity. If Europe is to lead in the 21st century, it must rediscover that ambition—not only in its policies, but in its identity. Without a shared sense of who Europeans are and what they stand for, the Union risks becoming a hollow structure, vulnerable to division and irrelevance. The future of Europe depends not only on what it builds, but on what it believes.

Recommended

Beyond U.S. Hegemony

One Chapter Closed, A Harder One Begins

What is the Ideal American Foreign Policy in the Multipolar World?

The Alliance’s Search for a New Identity

No More Free Rides in a Transactional World