The Lord of the Rings was a highly successful book series which was turned into the larger, much more successful film franchise. Its story rests on a premise that can be traced back through multiple channels, including the Bible and the verse quoted at the top. The main conceit of The Lord of the Rings is that there were multiple (9) rings of power, granting authority to those who possessed the nine rings, ruled by the highest ring of them all, the tenth. But the ring was a trap, it took as much as it gave. Currently, in our world, we can look around and see that there are an emerging number of strong, powerful nationalist leaders who are emerging all over the world, not just in one single continent.

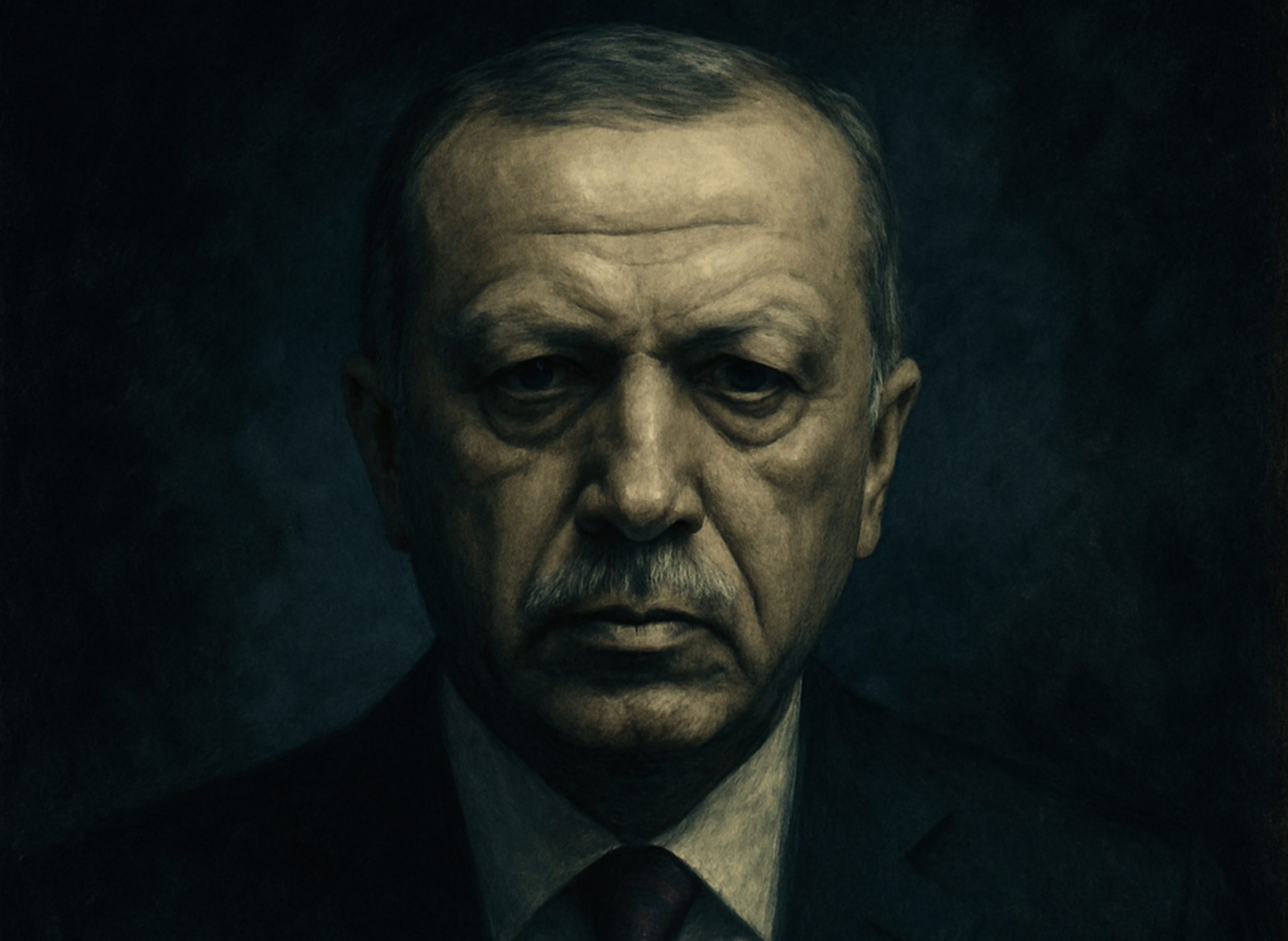

Other writers in this volume have covered Donald J. Trump and Viktor Orbán. In many ways, the two men of Asia, Benjamin Netanyahu and Recep Tayyip Erdogan, have emerged as leaders of Asia and have moved the world into a post-democratic, liberal world order and increasingly on the verge of single leadership. This article is dedicated to Erdogan. Recep Tayyip Erdogan began his rise to power in the early 2000s, and he was the first of the European strongmen to emerge and to remain in power. Though he was the first, he has not been the last, and can be seen as the initiating power behind this class of new strongmen.

Erdogan has been successful as he has sought the resurrection and reconstitution of the Ottoman Empire, in everything but name. With Türkiye sitting at the nexus of Asia, Europe, and the Middle East, he has sought to leverage this geographically strategic location into a means of creating not just a personal power base but a base upon which to establish Türkiye as the dominant force of these regions. By eliminating challenges to his own personal power and moving from liberal reformer to strongman, he has similarly placed Türkiye itself on a new path from being one of many nations in Europe and among the NATO alliance to becoming a force to be reckoned with.

His path to personal power and to a more powerful Türkiye has been through the strongman playbook. The creation of a political party answerable to himself, the initiation of substantial changes in the judicial system, extensive regulation of and antagonism with academia, an adversarial relationship with the media resulting in influence and power over it, changes to terms in office, and the labeling of all opposition as terrorism. These are an informal yet recognizable set of measures which have exploited the safeguards that democracies have set up to prevent the very rise that they have seen. This article will briefly trace the history of Erdogan’s rise and the implementation of these steps that he has undertaken from his appearance in 2003 until the present time.

It will then pivot to a brief analysis of his moves and, more importantly, his objectives, and finally will offer some thoughts on the future. Recep Tayyip Erdogan emerged in 2003, being elected as the Prime Minister at a time period when the world was largely focused on the Middle East proper, the war in Iraq was the dominant news item and Türkiye’s (as it was then written and known) role was subordinate. Most views of Türkiye at the time were that it was the quiet country, Türkiye was present but not making great waves in NATO or Europe. This had been its general position since its reforms post-World War One and even more so as the Cold War began.

M.A. is a research historian whose focus is on the Middle East and Combat studies at American Military University and one of authors of Boots & Suits.

Under the rule of a few, but strong quasi-dictators, Türkiye was seen but not heard in European circles. For Turkish observers, the rise of Erdogan was initially viewed with favor and as a man who could potentially lead Türkiye into a new era of European engagement. Erdogan, indeed, was viewed as someone that would bring Türkiye to great prominence but do so under the banner of constitutionalism and democracy. Indeed, in 2009 he was widely praised in an article that appeared in Foreign Policy Magazine. That article presented a fresh-faced, Western-friendly leader that was going to reshape Turkish politics but do so in a manner that could be praised by the rest of the world.

However, the timing of the article would become either greatly ironic or simply poorly chosen. By 2010, the dark clouds were gathering on the horizon. In 2010, he introduced a series of proposed changes to the constitution, largely moved and enabled through his Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi or the AKP). In the same spirit of past strongmen, and some current ones, Erdogan has fostered the majority of his rise through the establishment of this party. Erdogan has used this party to advance through what would have been normally very objectionable or questionable changes, including moving the country from the parliamentary system to that of a presidential system.

This has enabled him to aggregate more power into himself as the executive. He then moved against the judiciary. This process of advancing against the judiciary has been strategic and tactical in removing key pieces of legislation and judges that were inimical to his plan. In the same vein as prior strongmen, his attack on the judiciary has been carefully calibrated to weaken its institutional role not just in the government but in society as well in order to create and perpetuate the view of a hostile judiciary. These changes played on deep-seated discontent, areas for which there was obvious complaint and frustration within the general population, but many of those opened additional avenues to create deeper, more systemic ruptures.

By 2011 and 2012, the attacks on the judiciary had become outward attacks on the media and academic institutions. Moving to isolate and delegitimize those that were in a position to speak to the public and potentially control the narrative, Erdogan deftly swept aside many of his fiercest opponents into silence and near-total irrelevance. These attacks on academia took the form of removing academics, removing professors, and entire departments from academic institutions. According to an extensive report in Middle East Research and Information Project, the attacks on academia have a significant resemblance to current efforts underway in the U.S., yet have a distinctive Turkish flavor. In the purges, the government challenged academic freedom and integrity by focusing on the area of terrorism, an area not only deeply militarily resonant but also carrying an ethnic tone, that of the Kurds.

According to the report, many academics signed a petition calling for peace between the Turkish government and Kurdish forces that were fighting in the south of Türkiye and the north of Syria, the PKK. Just as in America, the academics were accused of supporting terrorists and perpetuating terrorist propaganda. Many professors lost their jobs in teaching, some merely forced out of it as a profession, and others were sentenced to jail time. The attacks on the media took on the nearly universally recognizable tone of attacking bias, partisanship, and essentially reducing all negative coverage to acts of antagonism against the government rather than legitimate criticism.

Under the rule of a few, but strong quasi-dictators, Türkiye was seen but not heard in European circles. For Turkish observers, the rise of Erdogan was initially viewed with favor and as a man who could potentially lead Türkiye into a new era of European engagement. Erdogan, indeed, was viewed as someone that would bring Türkiye to great prominence but do so under the banner of constitutionalism and democracy. Indeed, in 2009 he was widely praised in an article that appeared in Foreign Policy Magazine. That article presented a fresh-faced, Western-friendly leader that was going to reshape Turkish politics but do so in a manner that could be praised by the rest of the world.

However, the timing of the article would become either greatly ironic or simply poorly chosen. By 2010, the dark clouds were gathering on the horizon. In 2010, he introduced a series of proposed changes to the constitution, largely moved and enabled through his Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi or the AKP). In the same spirit of past strongmen, and some current ones, Erdogan has fostered the majority of his rise through the establishment of this party. Erdogan has used this party to advance through what would have been normally very objectionable or questionable changes, including moving the country from the parliamentary system to that of a presidential system.

This has enabled him to aggregate more power into himself as the executive. He then moved against the judiciary. This process of advancing against the judiciary has been strategic and tactical in removing key pieces of legislation and judges that were inimical to his plan. In the same vein as prior strongmen, his attack on the judiciary has been carefully calibrated to weaken its institutional role not just in the government but in society as well in order to create and perpetuate the view of a hostile judiciary. These changes played on deep-seated discontent, areas for which there was obvious complaint and frustration within the general population, but many of those opened additional avenues to create deeper, more systemic ruptures.

By 2011 and 2012, the attacks on the judiciary had become outward attacks on the media and academic institutions. Moving to isolate and delegitimize those that were in a position to speak to the public and potentially control the narrative, Erdogan deftly swept aside many of his fiercest opponents into silence and near-total irrelevance. These attacks on academia took the form of removing academics, removing professors, and entire departments from academic institutions. According to an extensive report in Middle East Research and Information Project, the attacks on academia have a significant resemblance to current efforts underway in the U.S., yet have a distinctive Turkish flavor. In the purges, the government challenged academic freedom and integrity by focusing on the area of terrorism, an area not only deeply militarily resonant but also carrying an ethnic tone, that of the Kurds.

According to the report, many academics signed a petition calling for peace between the Turkish government and Kurdish forces that were fighting in the south of Türkiye and the north of Syria, the PKK. Just as in America, the academics were accused of supporting terrorists and perpetuating terrorist propaganda. Many professors lost their jobs in teaching, some merely forced out of it as a profession, and others were sentenced to jail time. The attacks on the media took on the nearly universally recognizable tone of attacking bias, partisanship, and essentially reducing all negative coverage to acts of antagonism against the government rather than legitimate criticism.

The media was charged with conspiring with members of the government to institute their policies against the will of the people; thereby, the AKP accused their opponents of acting in a manner similar to their own. This frequently employed tactic of projection is used because it is often highly successful and shortcuts the process of logical thinking, exploiting the fears and anxieties of the people. While discussed in more detail below, the 2015 events with Syrian immigrants were not just about power politics against Europe, but may be seen as a test of European resolve and the limits to which Erdogan could exercise power.

It was an opportunity to determine to what degree Europe would let him set the agenda for both the Middle East and European regions. In that instance, he found that he had a substantial amount of safety and stability. Europe grudgingly acquiesced to his moves and did not threaten his position in Türkiye. There were no calls for his removal, and there were no plans to liberate Türkiye. Passing the removal test, Erdogan likely understood that he could be confident that there was little Europe would do if he pressed a little harder. During this same time, a key step which strongly signaled Erdogan’s ultimate aim was his reopening of Ottoman imperial-era barracks for soldiers in Istanbul.

He then restored elements of Ottoman symbols into the government iconography and took pictures replicating poses and backgrounds in Ottoman-era paintings. A much later, but still important, move of bringing Türkiye back to its roots has been the conversion of Hagia Sophia from a museum into a mosque. The former Christian church and then museum was converted into a functioning mosque, heightening the position of Islam back in Turkish life. The move appealed to religious Turks and, though possibly possessing some genuine religious aim, it was aimed at deflecting criticism of his rule and coopting the religious community.

The 2016 coup was Erdogan’s means of sealing his power. In the summer of that year, he engineered—or took strong advantage of—an attempted coup led by an exiled religious leader, Mohammad Fethullah Gulen, leader of the Gulen Organization. The sadly ironic nature of the coup was that the Gulen Organization, according to MERIP, had given the Erdogan government support, and many of their teachers had survived the academic purges of the earlier years with the cooperation of the AKP. The event in 2016 put that cooperation to a sudden end, and many, if not all, of the teachers who had emerged through the Gulen Organization found themselves thrown into jail or simply disappeared.

The coup itself did not last long; it was eliminated within a short week, yet the results would last for far longer. The result of the coup was that Erdogan was able to move against even more of the remaining opposition parties and forces in the country and to round up anyone that posed a potential problem to his rule. In some instances, there is a concern that he used false allegations of alignment with the movement to arrest political enemies and those he disagreed with, and that they had no means to challenge these accusations. It should be noted that the present writer lost a connection on professional webpages in the aftermath of that event, and no word has resurfaced as to their whereabouts.

The 2016 coup was Erdogan’s means of sealing his power.

Since the 2016 coup, he has moved from being Prime Minister to being president—and a president that has faced faux challenges in the electoral process. These “challengers” have allowed him to continue to window-dress the process in the clothing of democracy, but there is very little disguising the fact that the elections are predetermined and that he will ultimately win. However, the world has allowed this to continue, often appearing to believe that, as long as Türkiye is stable, then it is not worth making too much of an issue. However, during the last election cycle, evidence of Erdogan’s age has increasingly been on display.

He suffered a seizure during an interview and, while the video was ended, the audio continued to capture the moment. The moment reminded Western observers that, while Erdogan has become a strongman of Türkiye, his strength is not unlimited. Following that appearance and clear evidence that he was experiencing some slowdown in his physical capabilities, he announced that he would be retiring or not seeking re-election in 2028. It is hard to conceive of a situation where he may follow through on this unless he is substantially weakened. As we have seen in Israel and America, the baby boomer generation is having a difficult time letting go and retiring from their leadership and job roles with the grace and dignity of prior generations.

It is also difficult to part with such complete and unobstructed power and influence. In the opening of this article, it was suggested that Recep Tayyip Erdogan is in the process of reforming the Ottoman Empire. While he may not be seeking the precise name and designation of such, his work has largely set the stage for Türkiye to be in a dominant position. In regards to internal measures, beyond establishing a neo-sultanacy, Erdogan has allowed himself to be photographed in iconic Ottoman settings, posing on staircases and in other venues that have a direct relationship to Ottoman Sultans. As mentioned earlier, he has restored to working order barracks used by Ottoman soldiers, and this has had profound nationalistic implications and in many ways signaled that he was seeking to couch his legitimacy on deeper, embedded cultural associations.

As a scholar whose work has touched on these issues, it is clear that the means and the message were not accidental. Just as Sargon the Great built ziggurats in every key ancient leadership city of Mesopotamia to establish legitimacy, so Erdogan has touched on these key aspects of Ottoman authority to establish political legitimacy for extended rule. But, in addition to these symbolic and internal changes, he has added regional interactions and influence campaigning. Türkiye is, by virtue of its geographical location, in a highly influential position in terms of regional traffic flow for trade, but Erdogan has added to this by making all alliance roads between Europe, Asia, and the broader Arab and Persian Middle East run to and through Türkiye. The following is best understood if one imagines Erdogan standing on a vast map of Türkiye and looking at the nations that surround him.

Strongman Without Reach

In looking to his south, Erdogan can see an area of the world once ruled either by soft or hard power. His near abroad is defined by Syria, a state that until recently was more a territory than a state and lacked any central authority and direction. Currently, Erdogan is engaged in negotiating a long-term presence for Turkish troops in Syria, reoccupying bases formerly used by Syrian as well as Russian troops. With the presence of these troops and Israel’s extensive activities in the south, Türkiye and Israel are close to a collision in Syria at some point in the near future. While likely to begin as a collision between Syria and Israel, the status of forces agreement to be reached will likely include a clause requiring Türkiye to become involved in the case of Syrian requests for assistance.

Both Türkiye and Israel possess highly sophisticated and well-trained pilots, which will mean that the collision will be of greater consequence and duration than that between Israel and Iran. Turkish pilots are highly practiced and capable of mounting a significant defense. Another issue in Syria, northern Iraq, and northern Iran is the Kurdish issue. Erdogan has sought to bring an end to the Kurdish issue to the south, which has been (so far) successfully settled through the disarmament of the PKK. How enduring this disarmament will be is yet to be seen; for the present, it enables Erdogan to shift his attention to northern Iraq and to parts of Iran which Türkiye shares with its long border.

Northern Iraq remains a trouble spot; however, after years of attempting military solutions, it appears that the government is increasingly looking for political and domestic Iraqi means to resolve the conflict. Türkiye has been involved on the northern front since 2015 without any resolution. Northern Iran remains a more difficult matter. Erdogan has reached multiple defense and economic agreements with Iran. These would break down if he were to launch any military actions across their shared border. The hope is to give the resolution to the Iranians, just as in Iraq. Going a level further south, he has sought to intervene in the disputes between the Israelis and Palestinians.

In this context, he has attempted to portray himself as the chief defender of the Palestinian cause. This support has been manifested through a large number of diplomatic statements and warnings from himself directly and issued through his foreign ministry and longtime foreign minister Hakan Fidan. More substantial, physical means of support have included the portage, supplying, and facilitating of relief boats sent to the Gazans in order to aid in their relief from an economic and resource siege that began as early as 2005, near the time of Erdogan’s first entrance into Turkish politics. While none of these has been successful, their continued use has been a thorn in the side of Israel’s international relations, as these often enable Türkiye to portray the Israeli government in a negative light.

The influence that Erdogan has been able to assert does, however, appear to have reached its maximum extent in not penetrating the Arabian Peninsula. The leadership of the United Arab Emirates and also that of Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman in Saudi Arabia have served as effective breakwaters to the encroachment of Turkish power into the lower Middle East. The strong personality and leadership of Bin Salman and the national leadership of the UAE appear likely only to gain strength in the coming years and to present stronger challenges to Turkish measures. The only area in the Middle East where he has had complete success is in regard to the Kurdish issue. His strongman position has not yet made a measurable change in Palestine nor in the daily life of the majority of those in the Middle East.

Erdogan’s European Gamble

If Erdogan were to turn from the Middle East and view the Balkans region and then Europe beyond that to the north and northwest, he would see a more complex situation. Europe has long resisted, both militarily as well as diplomatically, Turkish entrance into European affairs. This has had some deleterious effects and has resulted in some level of reprisal on the part of Erdogan. In his immediate near abroad in Europe, he is looking at a still unstable Balkans region. The Balkans are still in some state of flux, and Türkiye is certainly working towards peace and stability in that region.

Serbia remains the most unstable of the countries, and restoration of stability would bring Türkiye some assurance that their most immediate trade networks in Europe were secure. Türkiye is one of the oldest members of the NATO alliance, yet they have not been allowed into the European Union, and it has long served as a major objective of Erdogan to enter into the alliance. He has attempted to manipulate his way into the economic and military alliance by leveraging soft power. In the summer and fall of 2015, he used this position by allowing nearly a million Syrians to cross Turkish borders and flood into Europe, causing a very damaging period of cultural, social, and economic chaos within Europe.

The massive influx of immigrants in Germany and in England produced two very substantial right-wing, nativist movements within Europe, which has reset the typical liberal orientation of the continent. In many ways, the rise of the strongman Viktor Orbán was a reaction to the processes set in motion by the strongman Erdogan. This human tsunami forced European nations to come and speak with him, and he leveraged the toll to receive many more concessions. Further attempts at leverage have been his ability to block the entry of Sweden and Finland into NATO, and it took a deep diplomatic crisis and several months of systemic engagement with Türkiye in order to allow Finland to enter into the military alliance. Sweden has been on Erdogan’s worst enemies list.

Türkiye has accused Sweden of various crimes against the Muslim community, including a general refusal to help the Muslim community. In looking at further Europe, France and England still dominate European politics, along with an emergent Poland. Two of these three nations, France and Poland, are currently setting the agenda for the European Union. It still may be an elusive goal, but if Erdogan can bring Türkiye into the bloc, it will be the most successful entry and the best, most beneficial cooperation bloc that Türkiye has been able to accede to. It has seemed that the most ardent, long-standing, and most active goals for Erdogan appear to be European-focused, with the Middle East constituting an important but secondary front in his orientation.

But, Erdogan is running out of time. The great equalizer of death is approaching, and he will not remain in power forever. The question is, how will his legacy and the state go forward from that moment? Future leadership is a key question, one that might be delayed because few leaders like to project that one day their power will be stripped by nature, if not by force of arms. Within authoritarian systems, this lack of leadership preparation takes on an added dimension as they are cautious about elevating a person who might decide that nature is taking too long and prefer to gain their new position in the short term.

This leads to a paradox in which there is awareness that there needs to be leadership training and stability, but it often comes too late for the successor, given that they have not had time to fully appreciate the magnitude of a role grown into by the established leader. In the case of Türkiye, there are three leading men who may fill this void and who would be necessary to fill the void. The most likely of those men will be Hakan Fidan. Fidan has been in a close position of power; being the former head of the Turkish intelligence agency, he has access to much more than just the dirt on Erdogan’s sons and family—he has the levers to start disappearing and moving them out of the way as he notes Erdogan’s decline.

The media was charged with conspiring with members of the government to institute their policies against the will of the people; thereby, the AKP accused their opponents of acting in a manner similar to their own. This frequently employed tactic of projection is used because it is often highly successful and shortcuts the process of logical thinking, exploiting the fears and anxieties of the people. While discussed in more detail below, the 2015 events with Syrian immigrants were not just about power politics against Europe, but may be seen as a test of European resolve and the limits to which Erdogan could exercise power.

It was an opportunity to determine to what degree Europe would let him set the agenda for both the Middle East and European regions. In that instance, he found that he had a substantial amount of safety and stability. Europe grudgingly acquiesced to his moves and did not threaten his position in Türkiye. There were no calls for his removal, and there were no plans to liberate Türkiye. Passing the removal test, Erdogan likely understood that he could be confident that there was little Europe would do if he pressed a little harder. During this same time, a key step which strongly signaled Erdogan’s ultimate aim was his reopening of Ottoman imperial-era barracks for soldiers in Istanbul.

He then restored elements of Ottoman symbols into the government iconography and took pictures replicating poses and backgrounds in Ottoman-era paintings. A much later, but still important, move of bringing Türkiye back to its roots has been the conversion of Hagia Sophia from a museum into a mosque. The former Christian church and then museum was converted into a functioning mosque, heightening the position of Islam back in Turkish life. The move appealed to religious Turks and, though possibly possessing some genuine religious aim, it was aimed at deflecting criticism of his rule and coopting the religious community.

The 2016 coup was Erdogan’s means of sealing his power. In the summer of that year, he engineered—or took strong advantage of—an attempted coup led by an exiled religious leader, Mohammad Fethullah Gulen, leader of the Gulen Organization. The sadly ironic nature of the coup was that the Gulen Organization, according to MERIP, had given the Erdogan government support, and many of their teachers had survived the academic purges of the earlier years with the cooperation of the AKP. The event in 2016 put that cooperation to a sudden end, and many, if not all, of the teachers who had emerged through the Gulen Organization found themselves thrown into jail or simply disappeared.

The coup itself did not last long; it was eliminated within a short week, yet the results would last for far longer. The result of the coup was that Erdogan was able to move against even more of the remaining opposition parties and forces in the country and to round up anyone that posed a potential problem to his rule. In some instances, there is a concern that he used false allegations of alignment with the movement to arrest political enemies and those he disagreed with, and that they had no means to challenge these accusations. It should be noted that the present writer lost a connection on professional webpages in the aftermath of that event, and no word has resurfaced as to their whereabouts.

The great equalizer of death is approaching, and he will not remain in power forever.

In his current role as Foreign Minister, he is much more exposed to the worldwide media as well as national leaders who are listening to his voice and getting used to his presence. This carries with it significant weight in terms of personality as well as authority. Fidan has also been a strong advocate and fighter against Israel as well as the Kurds, and he would be in the best position to take over the institutional flow of any efforts to maintain the military and intelligence campaigns against these two powers, one of which—Israel—may challenge Türkiye in the near future. Other analysts have preferred to view one of Erdogan’s sons, Necmaddin Bilal, as the more likely candidate.

He has reportedly built a very successful business empire and has a good grasp of management and economics. However, running a strong, nearly one-man state institution requires political acumen, understanding the processes of power, and the ability to work with entrenched leadership. Fidan more thoroughly possesses all of those qualities and would do so from day one. It is likely that a key sign of the changing of political leadership in Türkiye will be foreshadowed by the quick exit and virtual exile of any members of Erdogan’s family who may pose a challenge to the leadership of Fidan.

Whether Fidan has the same skills and leadership pull that Erdogan possesses will be quickly known. The lack of a successor may lead to a tarnishing of the Erdogan legacy. The question is: is that a good thing or one that is bad? Erdogan has restored Türkiye to a leading position in the region—one in which, as stated at the beginning, countries that surround it must take into account and consider what would happen if Türkiye were to intervene.

However, he is a strongman, and the legacy of strongmen does not often endure well or withstand the test of later history. The alienation and the impact that he has had on the religious group of the Gulen movement are yet to be fully explored and, in one way, have been personally felt, as this writer has known at least one person who may have disappeared as a result of her association with the group. Therefore, it cannot be said that the rise has been without consequence.

On the other hand, the future will tell whether this legacy will be supported, and what will happen to Türkiye will test the quality and the mettle of the changes made. If these changes quickly disappear, then the impact and legacy of Erdogan will be seen as ephemeral. If the changes endure—if there is continued respect and soft-and-hard foreign power in terms of the military as well as pure political power—then the leadership of Erdogan will likely be seen as one of those few moments when the means by which it was reached may not be looked down upon and will be evaluated as a means to an end.

Since the 2016 coup, he has moved from being Prime Minister to being president—and a president that has faced faux challenges in the electoral

process. These “challengers” have allowed him to continue to window-dress the process in the clothing of democracy, but there is very little disguising the fact that the elections are predetermined and that he will ultimately win. However, the world has allowed this to continue, often appearing to believe that, as long as Türkiye is stable, then it is not worth making too much of an issue. However, during the last election cycle, evidence of Erdogan’s age has increasingly been on display.

He suffered a seizure during an interview and, while the video was ended, the audio continued to capture the moment. The moment reminded Western observers that, while Erdogan has become a strongman of Türkiye, his strength is not unlimited. Following that appearance and clear evidence that he was experiencing some slowdown in his physical capabilities, he announced that he would be retiring or not seeking re-election in 2028. It is hard to conceive of a situation where he may follow through on this unless he is substantially weakened. As we have seen in Israel and America, the baby boomer generation is having a difficult time letting go and retiring from their leadership and job roles with the grace and dignity of prior generations.

It is also difficult to part with such complete and unobstructed power and influence. In the opening of this article, it was suggested that Recep Tayyip Erdogan is in the process of reforming the Ottoman Empire. While he may not be seeking the precise name and designation of such, his work has largely set the stage for Türkiye to be in a dominant position. In regards to internal measures, beyond establishing a neo-sultanacy, Erdogan has allowed himself to be photographed in iconic Ottoman settings, posing on staircases and in other venues that have a direct relationship to Ottoman Sultans. As mentioned earlier, he has restored to working order barracks used by Ottoman soldiers, and this has had profound nationalistic implications and in many ways signaled that he was seeking to couch his legitimacy on deeper, embedded cultural associations.

As a scholar whose work has touched on these issues, it is clear that the means and the message were not accidental. Just as Sargon the Great built ziggurats in every key ancient leadership city of Mesopotamia to establish legitimacy, so Erdogan has touched on these key aspects of Ottoman authority to establish political legitimacy for extended rule. But, in addition to these symbolic and internal changes, he has added regional interactions and influence campaigning. Türkiye is, by virtue of its geographical location, in a highly influential position in terms of regional traffic flow for trade, but Erdogan has added to this by making all alliance roads between Europe, Asia, and the broader Arab and Persian Middle East run to and through Türkiye. The following is best understood if one imagines Erdogan standing on a vast map of Türkiye and looking at the nations that surround him.

Strongman Without Reach

In looking to his south, Erdogan can see an area of the world once ruled either by soft or hard power. His near abroad is defined by Syria, a state that until recently was more a territory than a state and lacked any central authority and direction. Currently, Erdogan is engaged in negotiating a long-term presence for Turkish troops in Syria, reoccupying bases formerly used by Syrian as well as Russian troops. With the presence of these troops and Israel’s extensive activities in the south, Türkiye and Israel are close to a collision in Syria at some point in the near future. While likely to begin as a collision between Syria and Israel, the status of forces agreement to be reached will likely include a clause requiring Türkiye to become involved in the case of Syrian requests for assistance.

Both Türkiye and Israel possess highly sophisticated and well-trained pilots, which will mean that the collision will be of greater consequence and duration than that between Israel and Iran. Turkish pilots are highly practiced and capable of mounting a significant defense. Another issue in Syria, northern Iraq, and northern Iran is the Kurdish issue. Erdogan has sought to bring an end to the Kurdish issue to the south, which has been (so far) successfully settled through the disarmament of the PKK. How enduring this disarmament will be is yet to be seen; for the present, it enables Erdogan to shift his attention to northern Iraq and to parts of Iran which Türkiye shares with its long border.

Northern Iraq remains a trouble spot; however, after years of attempting military solutions, it appears that the government is increasingly looking for political and domestic Iraqi means to resolve the conflict. Türkiye has been involved on the northern front since 2015 without any resolution. Northern Iran remains a more difficult matter. Erdogan has reached multiple defense and economic agreements with Iran. These would break down if he were to launch any military actions across their shared border. The hope is to give the resolution to the Iranians, just as in Iraq. Going a level further south, he has sought to intervene in the disputes between the Israelis and Palestinians.

In this context, he has attempted to portray himself as the chief defender of the Palestinian cause. This support has been manifested through a large number of diplomatic statements and warnings from himself directly and issued through his foreign ministry and longtime foreign minister Hakan Fidan. More substantial, physical means of support have included the portage, supplying, and facilitating of relief boats sent to the Gazans in order to aid in their relief from an economic and resource siege that began as early as 2005, near the time of Erdogan’s first entrance into Turkish politics. While none of these has been successful, their continued use has been a thorn in the side of Israel’s international relations, as these often enable Türkiye to portray the Israeli government in a negative light.

The influence that Erdogan has been able to assert does, however, appear to have reached its maximum extent in not penetrating the Arabian Peninsula. The leadership of the United Arab Emirates and also that of Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman in Saudi Arabia have served as effective breakwaters to the encroachment of Turkish power into the lower Middle East. The strong personality and leadership of Bin Salman and the national leadership of the UAE appear likely only to gain strength in the coming years and to present stronger challenges to Turkish measures. The only area in the Middle East where he has had complete success is in regard to the Kurdish issue. His strongman position has not yet made a measurable change in Palestine nor in the daily life of the majority of those in the Middle East.

Erdogan’s European Gamble

If Erdogan were to turn from the Middle East and view the Balkans region and then Europe beyond that to the north and northwest, he would see a more complex situation. Europe has long resisted, both militarily as well as diplomatically, Turkish entrance into European affairs. This has had some deleterious effects and has resulted in some level of reprisal on the part of Erdogan. In his immediate near abroad in Europe, he is looking at a still unstable Balkans region. The Balkans are still in some state of flux, and Türkiye is certainly working towards peace and stability in that region.

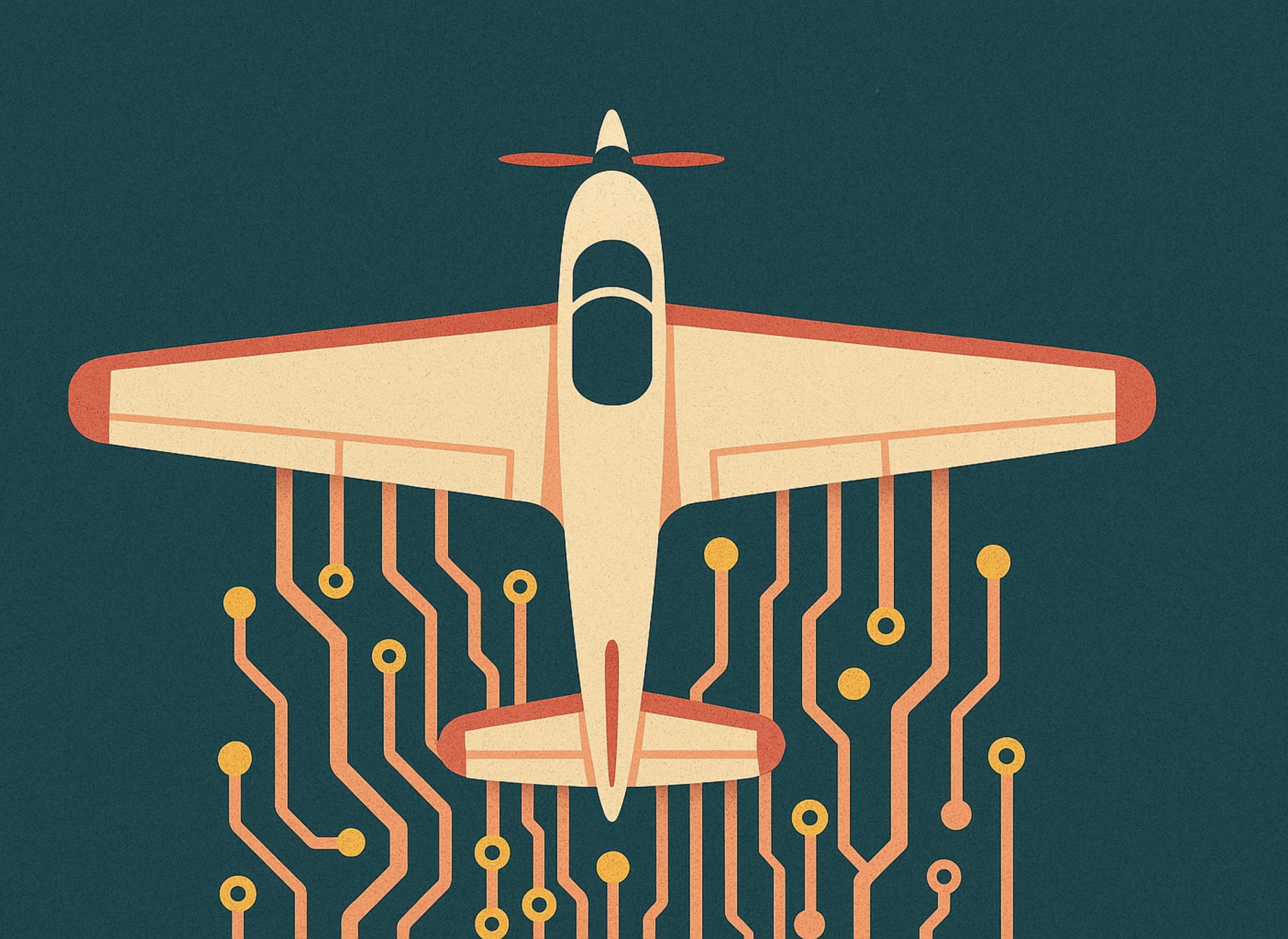

Serbia remains the most unstable of the countries, and restoration of stability would bring Türkiye some assurance that their most immediate trade networks in Europe were secure. Türkiye is one of the oldest members of the NATO alliance, yet they have not been allowed into the European Union, and it has long served as a major objective of Erdogan to enter into the alliance. He has attempted to manipulate his way into the economic and military alliance by leveraging soft power. In the summer and fall of 2015, he used this position by allowing nearly a million Syrians to cross Turkish borders and flood into Europe, causing a very damaging period of cultural, social, and economic chaos within Europe.

The massive influx of immigrants in Germany and in England produced two very substantial right-wing, nativist movements within Europe, which has reset the typical liberal orientation of the continent. In many ways, the rise of the strongman Viktor Orbán was a reaction to the processes set in motion by the strongman Erdogan. This human tsunami forced European nations to come and speak with him, and he leveraged the toll to receive many more concessions. Further attempts at leverage have been his ability to block the entry of Sweden and Finland into NATO, and it took a deep diplomatic crisis and several months of systemic engagement with Türkiye in order to allow Finland to enter into the military alliance. Sweden has been on Erdogan’s worst enemies list.

Türkiye has accused Sweden of various crimes against the Muslim community, including a general refusal to help the Muslim community. In looking at further Europe, France and England still dominate European politics, along with an emergent Poland. Two of these three nations, France and Poland, are currently setting the agenda for the European Union. It still may be an elusive goal, but if Erdogan can bring Türkiye into the bloc, it will be the most successful entry and the best, most beneficial cooperation bloc that Türkiye has been able to accede to. It has seemed that the most ardent, long-standing, and most active goals for Erdogan appear to be European-focused, with the Middle East constituting an important but secondary front in his orientation.

But, Erdogan is running out of time. The great equalizer of death is approaching, and he will not remain in power forever. The question is, how will his legacy and the state go forward from that moment? Future leadership is a key question, one that might be delayed because few leaders like to project that one day their power will be stripped by nature, if not by force of arms. Within authoritarian systems, this lack of leadership preparation takes on an added dimension as they are cautious about elevating a person who might decide that nature is taking too long and prefer to gain their new position in the short term.

This leads to a paradox in which there is awareness that there needs to be leadership training and stability, but it often comes too late for the successor, given that they have not had time to fully appreciate the magnitude of a role grown into by the established leader. In the case of Türkiye, there are three leading men who may fill this void and who would be necessary to fill the void. The most likely of those men will be Hakan Fidan. Fidan has been in a close position of power; being the former head of the Turkish intelligence agency, he has access to much more than just the dirt on Erdogan’s sons and family—he has the levers to start disappearing and moving them out of the way as he notes Erdogan’s decline.

In his current role as Foreign Minister, he is much more exposed to the worldwide media as well as national leaders who are listening to his voice and getting used to his presence. This carries with it

significant weight in terms of personality as well as authority. Fidan has also been a strong advocate and fighter against Israel as well as the Kurds, and he would be in the best position to take over the institutional flow of any efforts to maintain the military and intelligence campaigns against these two powers, one of which—Israel—may challenge Türkiye in the near future. Other analysts have preferred to view one of Erdogan’s sons, Necmaddin Bilal, as the more likely candidate.

He has reportedly built a very successful business empire and has a good grasp of management and economics. However, running a strong, nearly one-man state institution requires political acumen, understanding the processes of power, and the ability to work with entrenched leadership. Fidan more thoroughly possesses all of those qualities and would do so from day one. It is likely that a key sign of the changing of political leadership in Türkiye will be foreshadowed by the quick exit and virtual exile of any members of Erdogan’s family who may pose a challenge to the leadership of Fidan.

Whether Fidan has the same skills and leadership pull that Erdogan possesses will be quickly known. The lack of a successor may lead to a tarnishing of the Erdogan legacy. The question is: is that a good thing or one that is bad? Erdogan has restored Türkiye to a leading position in the region—one in which, as stated at the beginning, countries that surround it must take into account and consider what would happen if Türkiye were to intervene.

However, he is a strongman, and the legacy of strongmen does not often endure well or withstand the test of later history. The alienation and the impact that he has had on the religious group of the Gulen movement are yet to be fully explored and, in one way, have been personally felt, as this writer has known at least one person who may have disappeared as a result of her association with the group. Therefore, it cannot be said that the rise has been without consequence.

On the other hand, the future will tell whether this legacy will be supported, and what will happen to Türkiye will test the quality and the mettle of the changes made. If these changes quickly disappear, then the impact and legacy of Erdogan will be seen as ephemeral. If the changes endure—if there is continued respect and soft-and-hard foreign power in terms of the military as well as pure political power—then the leadership of Erdogan will likely be seen as one of those few moments when the means by which it was reached may not be looked down upon and will be evaluated as a means to an end.

Recommended

Can Ukraine Win Without Losing?

War Without End?

How Semiconductors Shape the New World Order

Soft Power, Hard Tactics, and U.S. Resistance

No More Free Rides in a Transactional World