As one of the most consequential political figures of the 21st century, Vladimir Putin has come to embody Russia on the world stage. A former KGB officer who was hand-picked by his predecessor, Putin has shaped Russia’s political, geopolitical, and ideological trajectory following the turbulent 1990s. Over the last two decades, he carefully cultivated a tightly controlled image of strength that he projects globally. Today, he dominates conversations on autocracy, global security, and war.

Before his name became synonymous with modern Russia and autocracy, Putin was somewhat of an unknown figure operating behind the scenes, leveraging the uncertainty of the post-Soviet collapse and laying the foundation for his political rise. Understanding Putin’s ascent to his decades-long presidency and his tools of control is indispensable for grasping how personalist rule can take root, endure, and ultimately redefine the boundaries of modern autocracy, which are often cloaked in the façade of democracy.

The Putin Era Begins

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the years that followed placed Russia under intense scrutiny. Questions remained about how the country could establish itself within the international system, transition to a democracy, and rebuild its economy. Under President Boris Yeltsin, Russia remained formally committed to becoming a democratic market state integrated into the international system. However, Yeltsin’s goals failed to materialize, and new problems emerged, including the rise of a new class of oligarchs. Yeltsin’s Russia saw the exaggerated power of the presidency, weak accountability, immense privatization, and deep entanglement of economic interests in political decision-making.

By the end of the 1990s, it was clear that Yeltsin’s vision of Russia was out of reach. The country was thrown into chaos due to economic instability and inflation. Meanwhile, Yeltsin himself attracted criticism for his erratic behavior, appearing visibly intoxicated at official events and public appearances. By this time, political opposition was also growing, with favorable odds to win the election against Yeltsin. When Yeltsin resigned in 1999, however, the Kremlin already had a successor ready who appeared to be his complete opposite: a young, sober, and disciplined former KGB officer who could instill hope in the Russian people and project an image of stability.

What swung the public in Putin’s favor was a series of events in 1999, where several explosions across Russia killed hundreds of civilians. As prime minister, Vladimir Putin responded by sending the Russian military into Chechnya, blaming it for the attacks. Conveniently, the timing proved advantageous: the military assault boosted his approval ratings and cast him in sharp contrast with Yeltsin’s erratic leadership. Most importantly, it offered a template for using such domestic security crises as a means of rallying public support and legitimizing his executive authority. This approach would remain in place throughout his presidency.

M.A. in International Affairs from the George Washington University, specializes in conflict prevention, peacebuilding, post-Soviet politics, and international security.

When Vladimir Putin officially became president in 2000, he quickly understood that many Russians longed for a strong state with a leader who could restore national pride, even at the expense of reconciliation with the West. His presidency began with a clear objective: to centralize authority and consolidate executive power to strengthen the “power vertical”—ensuring that reforms were driven solely from the Kremlin, insulated from competing political actors. Putin’s background in the KGB during the chaotic 1980s and 1990s played a key role in his governing approach as it reinforced his conviction that only centralized strength could shield Russia from further humiliation and internal fragmentation.

To plant the seeds of his autocratic ascent, Putin launched a calculated campaign against oligarchs who openly challenged his authority. He drove them into exile and seized their assets, using the reclaimed wealth to consolidate state control over key industries and media outlets. This allowed Putin to expand his grip on state-owned newspapers and television channels, which became a platform to curate the image of Putin throughout his leadership. In this way, he eliminated alternative centers of power within Russia’s post-Soviet system and laid the groundwork for his unchallenged authority.

The expansion of state-owned television and media was not merely a propaganda tool but a pillar of his regime’s survival, ensuring that dissenting voices would remain marginalized. Yet, Putin’s consolidation of power was not sealed from the beginning. Instead, it took years of restructuring his inner circle and placing the so-called “siloviki” around him, enduring moments of political humiliation and vulnerability, and crafting a deliberate, intentional strategy on a global scale to position Russia as a Great Power.

The 2007 Munich Security Conference became a turning point. There, Putin openly challenged the U.S.-led security order, accusing Washington of “overstepping its national borders in every way” and imposing a unipolar world detrimental to global stability. This was more than diplomatic theater—it was a public declaration that confronting the West would serve as both a foreign policy and a domestic legitimacy strategy, positioning Russia as the defender of sovereignty against foreign encroachment.

The Putin Constitution

By 2008, Putin still had not pushed the limits of Russia’s domestic legal archetype. He stepped down from the presidency due to constitutional term limits, installing his successor, Dmitry Medvedev, as president while assuming the role of prime minister himself. Such “tandemocracy” allowed him to retain control and continue to shape domestic and foreign policy. The arrangement also signaled that Putin’s authority was the real source of power in Russia, with Medvedev serving mainly as a figurehead. At the same time, Putin tested boundaries, pushed legal and political red lines, and laid the groundwork for his eventual return as the country’s long-term autocrat.

When Vladimir Putin officially became president in 2000, he quickly understood that many Russians longed for a strong state with a leader who could restore national pride, even at the expense of reconciliation with the West. His presidency began with a clear objective: to centralize authority and consolidate executive power to strengthen the “power vertical”—ensuring that reforms were driven solely from the Kremlin, insulated from competing political actors. Putin’s background in the KGB during the chaotic 1980s and 1990s played a key role in his governing approach as it reinforced his conviction that only centralized strength could shield Russia from further humiliation and internal fragmentation.

To plant the seeds of his autocratic ascent, Putin launched a calculated campaign against oligarchs who openly challenged his authority. He drove them into exile and seized their assets, using the reclaimed wealth to consolidate state control over key industries and media outlets. This allowed Putin to expand his grip on state-owned newspapers and television channels, which became a platform to curate the image of Putin throughout his leadership. In this way, he eliminated alternative centers of power within Russia’s post-Soviet system and laid the groundwork for his unchallenged authority.

The expansion of state-owned television and media was not merely a propaganda tool but a pillar of his regime’s survival, ensuring that dissenting voices would remain marginalized. Yet, Putin’s consolidation of power was not sealed from the beginning. Instead, it took years of restructuring his inner circle and placing the so-called “siloviki” around him, enduring moments of political humiliation and vulnerability, and crafting a deliberate, intentional strategy on a global scale to position Russia as a Great Power.

The 2007 Munich Security Conference became a turning point. There, Putin openly challenged the U.S.-led security order, accusing Washington of “overstepping its national borders in every way” and imposing a unipolar world detrimental to global stability. This was more than diplomatic theater—it was a public declaration that confronting the West would serve as both a foreign policy and a domestic legitimacy strategy, positioning Russia as the defender of sovereignty against foreign encroachment.

The Putin Constitution

By 2008, Putin still had not pushed the limits of Russia’s domestic legal archetype. He stepped down from the presidency due to constitutional term limits, installing his successor, Dmitry Medvedev, as president while assuming the role of prime minister himself. Such “tandemocracy” allowed him to retain control and continue to shape domestic and foreign policy. The arrangement also signaled that Putin’s authority was the real source of power in Russia, with Medvedev serving mainly as a figurehead. At the same time, Putin tested boundaries, pushed legal and political red lines, and laid the groundwork for his eventual return as the country’s long-term autocrat.

The same year, Russia invaded Georgia, reinforcing the idea that Russia was prepared to defend what it perceived as its sphere of influence through force, while domestically reinforcing the image of Putin as a leader who could restore Russia’s status as a great power. By the end of Medvedev’s four-year term, Putin had managed to extend the presidential term limit to six years and expressed his intention to run again. However, Putin’s return to the presidency did not come easily. The 2011-2012 election cycle presented challenges for the country’s leadership, as large-scale protests erupted due to electoral fraud and Putin’s decision to return.

Despite massive public unrest, Putin was declared president, which was followed by his enacted legislation to elevate penalties for protesters who pose a threat to his regime. His new term marked the beginning of a full-blown autocracy, as Putin actively resumed curbing civil liberties, eliminating and oppressing political opposition, and further expanding restrictions on independent media. The increased social repression during Putin’s third term was aimed at ensuring the survival of his regime. As he realized that his ratings were falling and the forged myth of his leadership competence was wavering, Putin was in desperate need of a renewed approach.

One of the components of the renewed autocracy was additional mechanisms of repression, including the well-known 2012 “foreign agents” law, which labeled non-governmental organizations receiving financing from abroad as instruments of foreign influence (or foreign agents), eventually limiting them from finding alternative funding sources and curtailing independent activism. During this period, Putin also tightened his grip on state-owned media outlets and jailed his political opponents, including Alexey Navalny, Sergei Udalstov, and Leonid Razvozzhayev. Putin’s regime even went to extremes, assassinating Boris Nemtsov, the former deputy prime minister and a vocal critic of Putin, in 2015.

However, the physical tools of oppression were not effective; the political machine of oppression could not be solely constructed on a brutal grasp on power. This approach silenced the opponents of Putin’s regime, but it did not rally the public in his favor. Learning from the experience of the color revolutions in Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan, Putin understood that the regime needed a story that would rally Russians behind the autocrat—one rooted in Russian history and glory, forged as a myth of Russian identity against Western influence, which identified a clear enemy of Russia and its traditional values.

In 2014, Putin reinforced this narrative by annexing what he perceived as Russia’s sphere of influence—Crimea. Putin enforced the narrative that adversarial Western forces were attempting to seize Ukraine by ousting the Russian-allied President Viktor Yanukovych. While Putin’s initial plan in Ukraine did not go as planned and Ukraine greeted a pro-Western leadership regardless, his objective of regime survival and perpetuating the historical narrative of returning Greater Russia with its historic sphere of influence would persist. Russia’s military intervention in the Syrian civil war, which transformed the conflict into a proxy war between the U.S. and Russia, was an attempt to recover the country’s status as a Great Power yet again.

His new term marked the beginning of a full-blown autocracy.

In his speech to the U.N., Putin underlined that it was Russia’s duty to support Assad’s regime in fighting terrorism, stating that Russia “could no longer tolerate the current state of affairs in the world.” By challenging the U.S. directly on foreign soil and justifying the intervention, Putin made a strategic move to reestablish Russia’s influence on the global stage and demonstrate its ability to shape international affairs. Shaping world politics in line with a country’s interests is a defining feature of a Great Power and projects power both domestically and internationally. In 2016, two years before the 2018 presidential elections, Vladimir Putin established a National Guard that bypassed the Ministry of Defense and answered directly to him.

By placing his judo partner and a former bodyguard, Viktor Zolotov, as head of the Rosgvardiya, Putin guaranteed its loyalty, needed for countering terrorism, maintaining public order, monitoring opposition, and suppressing public unrest when needed. In 2018, the so-called “siloviki,” or the people with a state security background, also reached their zenith. Coming from a KGB background himself, Putin’s individualistic politics led him to reshape his inner circle of decision-makers by appointing the siloviki who could resort to force to curb opposition and carry out his tasks. In 2020, Vladimir Putin passed constitutional reforms through a national vote, which further entrenched his political authority.

The central political change was amending the constitution by resetting Putin’s presidential term counts and allowing him to run for two more six-year terms. In addition to allowing Putin to remain as president until 2036, the 2020 reforms brought about institutional reshaping that increased presidential powers in relation to the judiciary. The amendments also marked the continuation of the Russian myth narrative, as they embedded nationalist ideas of defining marriage as a union between a man and a woman and affirming the belief in God as Russia’s national heritage. Through these political maneuvers, Putin systematically eroded the existing legal norms and engineered a political system centered on his authority.

By eliminating the lines between state institutions and his power, he created an architecture of ultimate control that combined ideology, coercion, legal manipulation, mythmaking, and repression. Each point in Putin’s path to engineering his unchallenged authority as a Russian leader reinforces the notion that the country’s stability and greatness are almost inseparable from Putin himself. Putin’s personalist politics of power were further reinforced by the revival and forging of imperial-historical myth, portraying Russia as a great empire, with countries like Ukraine cast as inherent parts of the Greater Russia.

History as a Weapon

To perpetuate his resilient image of a strongman defending Russia from the adversarial West and its “non-traditional values,” Putin could not tolerate the prospect of a democratic and prosperous Ukraine, since its success risked inspiring Russians to question and resist his increasingly autocratic rule. Such a Ukraine would also undermine Putin’s constructed myth that the country not only belongs within Russia’s sphere of influence but is also an inseparable part of its historical identity. This narrative was formalized in July 2021, when Putin published his essay On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians, in which he argued that Russians and Ukrainians are “one people” who were divided as a consequence of foreign interference.

By constructing the narrative as such, Putin attempted to justify the subsequent invasion and frame it as legitimate in the eyes of the Russian public. The invasion of Ukraine, therefore, serves not only as a geopolitical tool in Putin’s handbook to expand his sphere of influence and challenge the West, but also as his performance as the guardian of Russian history and protector of the country’s national pride. To sustain this image and global prestige, Putin tapped into disinformation as a weapon. By filling both domestic and overseas information spaces with conspiracy theories, myths, and fiction, he manipulated history and wartime facts to strengthen anti-Western rhetoric and challenge cohesive resistance to the war.

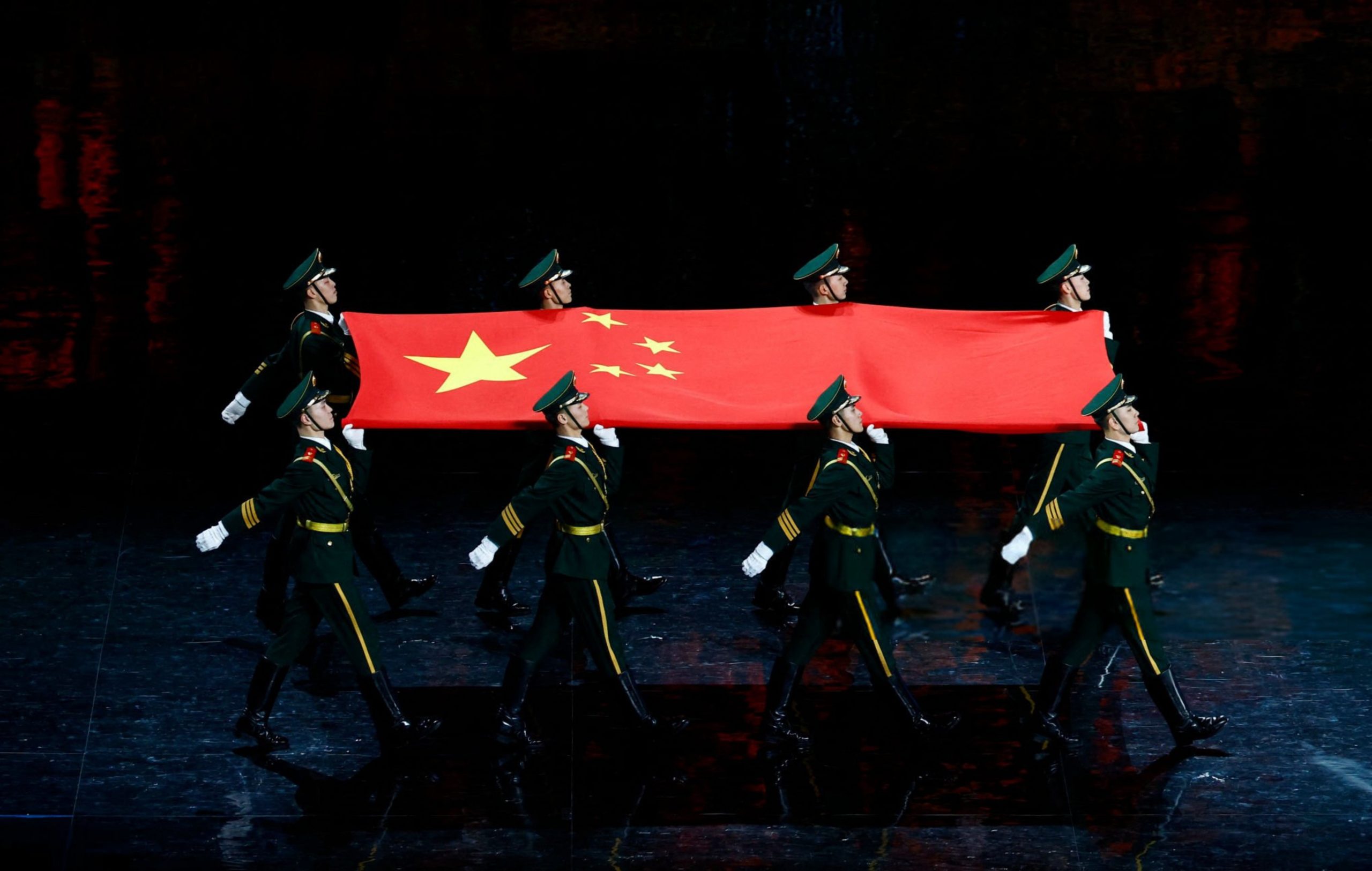

As the world sought to isolate Russia and punish it for its aggression, Putin focused on its strategic relationships with China, Iran, and other allied countries to escape entrapment and the repercussions of sanctions. He leveraged energy exports and food insecurity as pressure points, while increasing the Russian Central Bank’s interest rates to 20% immediately after the invasion to curb inflation. These tools, however, could not mask the underlying weaknesses that have plagued Putin’s regime since 2022. Military setbacks in Ukraine exposed the gaps in Russia’s great power image, sanctions strained its economy, and the grip on international influence remains under question.

From Weakness to Fortress Russia

Putin’s ability to maintain power for more than two decades is based on a carefully balanced mix of elite loyalty and widespread fear. Such a political equilibrium has so far prevented the fragmentation of Russia’s ruling structure. In an authoritarian system, the leader’s survival often hinges on ensuring that no rival can accumulate enough influence to pose a challenge, while also avoiding the alienation of key stakeholders. Putin achieved this through a combination of patronage networks, targeted coercion, and controlled political competition from the outset of his presidency. These measures ensure that the elites remain dependent on his continued rule while fearing the consequences of defection.

By rotating officials, playing competing factions against each other, and reserving high-profile prosecutions for those who overstep, Putin keeps the system tightly bound to his personal authority. The rise of siloviki in his inner circle also guarantees that Putin’s decision-making apparatus is rooted in a hard, autocratic approach where ends justify the means. One of the central elements of Putin’s durability is his exploitation of historical grievances and false narratives to rally national unity and incite nationalism. Putin has long framed Russia as a besieged fortress, threatened externally by NATO expansion and the “collective West,” and internally by instability reminiscent of the chaotic 1990s.

This narrative is not merely propaganda. It taps into deeply embedded cultural and historical experiences, including memories of the Soviet collapse, and the perceived humiliation of the post–Cold War settlement. By presenting himself as the guardian of Russian sovereignty and dignity, Putin transforms external pressure into an instrument of domestic consolidation. Military campaigns, such as the 2008 war in Georgia, the 2014 annexation of Crimea, and the ongoing full-scale war in Ukraine since 2022, have been used to reinforce this narrative, portraying Russia as reclaiming its rightful place in the world.

The same year, Russia invaded Georgia, reinforcing the idea that Russia was prepared to defend what it perceived as its sphere of influence through force, while domestically reinforcing the image of Putin as a leader who could restore Russia’s status as a great power. By the end of Medvedev’s four-year term, Putin had managed to extend the presidential term limit to six years and expressed his intention to run again. However, Putin’s return to the presidency did not come easily. The 2011-2012 election cycle presented challenges for the country’s leadership, as large-scale protests erupted due to electoral fraud and Putin’s decision to return.

Despite massive public unrest, Putin was declared president, which was followed by his enacted legislation to elevate penalties for protesters who pose a threat to his regime. His new term marked the beginning of a full-blown autocracy, as Putin actively resumed curbing civil liberties, eliminating and oppressing political opposition, and further expanding restrictions on independent media. The increased social repression during Putin’s third term was aimed at ensuring the survival of his regime. As he realized that his ratings were falling and the forged myth of his leadership competence was wavering, Putin was in desperate need of a renewed approach.

One of the components of the renewed autocracy was additional mechanisms of repression, including the well-known 2012 “foreign agents” law, which labeled non-governmental organizations receiving financing from abroad as instruments of foreign influence (or foreign agents), eventually limiting them from finding alternative funding sources and curtailing independent activism. During this period, Putin also tightened his grip on state-owned media outlets and jailed his political opponents, including Alexey Navalny, Sergei Udalstov, and Leonid Razvozzhayev. Putin’s regime even went to extremes, assassinating Boris Nemtsov, the former deputy prime minister and a vocal critic of Putin, in 2015.

However, the physical tools of oppression were not effective; the political machine of oppression could not be solely constructed on a brutal grasp on power. This approach silenced the opponents of Putin’s regime, but it did not rally the public in his favor. Learning from the experience of the color revolutions in Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan, Putin understood that the regime needed a story that would rally Russians behind the autocrat—one rooted in Russian history and glory, forged as a myth of Russian identity against Western influence, which identified a clear enemy of Russia and its traditional values.

In 2014, Putin reinforced this narrative by annexing what he perceived as Russia’s sphere of influence—Crimea. Putin enforced the narrative that adversarial Western forces were attempting to seize Ukraine by ousting the Russian-allied President Viktor Yanukovych. While Putin’s initial plan in Ukraine did not go as planned and Ukraine greeted a pro-Western leadership regardless, his objective of regime survival and perpetuating the historical narrative of returning Greater Russia with its historic sphere of influence would persist. Russia’s military intervention in the Syrian civil war, which transformed the conflict into a proxy war between the U.S. and Russia, was an attempt to recover the country’s status as a Great Power yet again.

Military setbacks in Ukraine exposed the gaps in Russia’s great power image.

Another key to his longevity is strategic adaptability, particularly his willingness to make tactical retreats without conceding strategic goals. Putin has repeatedly shown that he can recalibrate policy in response to domestic discontent or international setbacks. When protests over pension reforms in 2018 threatened to erode his legitimacy, he softened specific measures. When Western sanctions after 2014 weakened the Russian economy, he shifted trade toward China, India, and other non-Western markets, while also promoting import substitution policies in agriculture and industry. However, in each case, the long-term direction of policy, such as centralizing political power, expanding military influence, and asserting Russia’s role as a great power, remained unchanged.

This flexibility allowed him to absorb shocks without destabilizing the system, while keeping his ultimate objectives intact. It is also true, however, that Putin’s cult of personality plays a role in his endurance. At the beginning of his leadership, Putin played into the idea that he was the exact opposite of Yeltsin. While Yeltsin was a drunk and an unfit man, Putin was young, sharp, and most importantly, sober. While one projected an image of instability and chaos, the other exuded confidence and strength. During Yeltsin’s tenure, Russia was perceived as weak both abroad and domestically. Today, Russia stands strong and challenges international regimes.

Often, its strength is equated with Putin’s physical image—one of a man in his 70s with perfect health and undisputed international prestige. To create an image of a patriotic, Russia-loving Vladimir Putin and attract the public, the Kremlin had to resort to using “machismo” propaganda. Pictures of Putin shirtless on a horse, fishing, and swimming in rivers circulated heavily among the public throughout his presidency. The images of Putin, emphasizing physical masculinity, aimed to create a sense of desirability in a leader. While a product of Kremlin image-makers, such propaganda ensured that Putin’s persona became intertwined with nationalism, as he engaged in activities traditionally attributed to male strength and dominance.

The combination of rigidity in strategic vision and flexibility in tactics created what can be described as the “Putin paradox.” He appears indispensable to the functioning of the Russian state, even as the costs of his leadership mount both internally and externally. Domestically, economic stagnation, demographic decline, corruption, and a narrowing base of political talent raise questions about the sustainability of his model. Internationally, prolonged confrontation with the West, reputational damage, and resource-draining military operations strain Russia’s capacity to project power.

Yet these very challenges reinforce the perception among the elites and much of the public that without Putin at the helm, the state would face fragmentation or collapse. In this way, Putin’s endurance is not only the product of his personal authority but also of a political architecture he has built to make his removal appear too risky for those within the system. The interplay of loyalty, fear, historical narrative, and adaptive governance ensures that even as pressures accumulate, the structure holds, at least for now.

The Endgame of Control

Putin’s political model illustrates both the resilience and fragility inherent in personalist autocracies. For more than two decades, he has successfully concentrated power by dismantling institutional checks, forging historical narratives, using repression, and altering legislation. Yet such concentration of authority is bound to leave the system vulnerable: repression cannot remain perpetual, and the risks of public discontent increase. Additionally, in the absence of institutional checks and regulations, questions loom about potential successors to Putin. This is the paradox of Putin’s hard rule: the very strength of his personality politics exposes the regime’s fragility, even as he has revived the myth of Russian imperial destiny—an ideological framework that continues to resonate with his people and shape the logic of his governance.

In his speech to the U.N., Putin underlined that it was Russia’s duty to support Assad’s regime in fighting terrorism, stating that Russia “could

no longer tolerate the current state of affairs in the world.” By challenging the U.S. directly on foreign soil and justifying the intervention, Putin made a strategic move to reestablish Russia’s influence on the global stage and demonstrate its ability to shape international affairs. Shaping world politics in line with a country’s interests is a defining feature of a Great Power and projects power both domestically and internationally. In 2016, two years before the 2018 presidential elections, Vladimir Putin established a National Guard that bypassed the Ministry of Defense and answered directly to him.

By placing his judo partner and a former bodyguard, Viktor Zolotov, as head of the Rosgvardiya, Putin guaranteed its loyalty, needed for countering terrorism, maintaining public order, monitoring opposition, and suppressing public unrest when needed. In 2018, the so-called “siloviki,” or the people with a state security background, also reached their zenith. Coming from a KGB background himself, Putin’s individualistic politics led him to reshape his inner circle of decision-makers by appointing the siloviki who could resort to force to curb opposition and carry out his tasks. In 2020, Vladimir Putin passed constitutional reforms through a national vote, which further entrenched his political authority.

The central political change was amending the constitution by resetting Putin’s presidential term counts and allowing him to run for two more six-year terms. In addition to allowing Putin to remain as president until 2036, the 2020 reforms brought about institutional reshaping that increased presidential powers in relation to the judiciary. The amendments also marked the continuation of the Russian myth narrative, as they embedded nationalist ideas of defining marriage as a union between a man and a woman and affirming the belief in God as Russia’s national heritage. Through these political maneuvers, Putin systematically eroded the existing legal norms and engineered a political system centered on his authority.

By eliminating the lines between state institutions and his power, he created an architecture of ultimate control that combined ideology, coercion, legal manipulation, mythmaking, and repression. Each point in Putin’s path to engineering his unchallenged authority as a Russian leader reinforces the notion that the country’s stability and greatness are almost inseparable from Putin himself. Putin’s personalist politics of power were further reinforced by the revival and forging of imperial-historical myth, portraying Russia as a great empire, with countries like Ukraine cast as inherent parts of the Greater Russia.

History as a Weapon

To perpetuate his resilient image of a strongman defending Russia from the adversarial West and its “non-traditional values,” Putin could not tolerate the prospect of a democratic and prosperous Ukraine, since its success risked inspiring Russians to question and resist his increasingly autocratic rule. Such a Ukraine would also undermine Putin’s constructed myth that the country not only belongs within Russia’s sphere of influence but is also an inseparable part of its historical identity. This narrative was formalized in July 2021, when Putin published his essay On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians, in which he argued that Russians and Ukrainians are “one people” who were divided as a consequence of foreign interference.

By constructing the narrative as such, Putin attempted to justify the subsequent invasion and frame it as legitimate in the eyes of the Russian public. The invasion of Ukraine, therefore, serves not only as a geopolitical tool in Putin’s handbook to expand his sphere of influence and challenge the West, but also as his performance as the guardian of Russian history and protector of the country’s national pride. To sustain this image and global prestige, Putin tapped into disinformation as a weapon. By filling both domestic and overseas information spaces with conspiracy theories, myths, and fiction, he manipulated history and wartime facts to strengthen anti-Western rhetoric and challenge cohesive resistance to the war.

As the world sought to isolate Russia and punish it for its aggression, Putin focused on its strategic relationships with China, Iran, and other allied countries to escape entrapment and the repercussions of sanctions. He leveraged energy exports and food insecurity as pressure points, while increasing the Russian Central Bank’s interest rates to 20% immediately after the invasion to curb inflation. These tools, however, could not mask the underlying weaknesses that have plagued Putin’s regime since 2022. Military setbacks in Ukraine exposed the gaps in Russia’s great power image, sanctions strained its economy, and the grip on international influence remains under question.

From Weakness to Fortress Russia

Putin’s ability to maintain power for more than two decades is based on a carefully balanced mix of elite loyalty and widespread fear. Such a political equilibrium has so far prevented the fragmentation of Russia’s ruling structure. In an authoritarian system, the leader’s survival often hinges on ensuring that no rival can accumulate enough influence to pose a challenge, while also avoiding the alienation of key stakeholders. Putin achieved this through a combination of patronage networks, targeted coercion, and controlled political competition from the outset of his presidency. These measures ensure that the elites remain dependent on his continued rule while fearing the consequences of defection.

By rotating officials, playing competing factions against each other, and reserving high-profile prosecutions for those who overstep, Putin keeps the system tightly bound to his personal authority. The rise of siloviki in his inner circle also guarantees that Putin’s decision-making apparatus is rooted in a hard, autocratic approach where ends justify the means. One of the central elements of Putin’s durability is his exploitation of historical grievances and false narratives to rally national unity and incite nationalism. Putin has long framed Russia as a besieged fortress, threatened externally by NATO expansion and the “collective West,” and internally by instability reminiscent of the chaotic 1990s.

This narrative is not merely propaganda. It taps into deeply embedded cultural and historical experiences, including memories of the Soviet collapse, and the perceived humiliation of the post–Cold War settlement. By presenting himself as the guardian of Russian sovereignty and dignity, Putin transforms external pressure into an instrument of domestic consolidation. Military campaigns, such as the 2008 war in Georgia, the 2014 annexation of Crimea, and the ongoing full-scale war in Ukraine since 2022, have been used to reinforce this narrative, portraying Russia as reclaiming its rightful place in the world.

Another key to his longevity is strategic adaptability, particularly his willingness to make tactical retreats without conceding strategic goals. Putin has repeatedly shown that he

can recalibrate policy in response to domestic discontent or international setbacks. When protests over pension reforms in 2018 threatened to erode his legitimacy, he softened specific measures. When Western sanctions after 2014 weakened the Russian economy, he shifted trade toward China, India, and other non-Western markets, while also promoting import substitution policies in agriculture and industry. However, in each case, the long-term direction of policy, such as centralizing political power, expanding military influence, and asserting Russia’s role as a great power, remained unchanged.

This flexibility allowed him to absorb shocks without destabilizing the system, while keeping his ultimate objectives intact. It is also true, however, that Putin’s cult of personality plays a role in his endurance. At the beginning of his leadership, Putin played into the idea that he was the exact opposite of Yeltsin. While Yeltsin was a drunk and an unfit man, Putin was young, sharp, and most importantly, sober. While one projected an image of instability and chaos, the other exuded confidence and strength. During Yeltsin’s tenure, Russia was perceived as weak both abroad and domestically. Today, Russia stands strong and challenges international regimes.

Often, its strength is equated with Putin’s physical image—one of a man in his 70s with perfect health and undisputed international prestige. To create an image of a patriotic, Russia-loving Vladimir Putin and attract the public, the Kremlin had to resort to using “machismo” propaganda. Pictures of Putin shirtless on a horse, fishing, and swimming in rivers circulated heavily among the public throughout his presidency. The images of Putin, emphasizing physical masculinity, aimed to create a sense of desirability in a leader. While a product of Kremlin image-makers, such propaganda ensured that Putin’s persona became intertwined with nationalism, as he engaged in activities traditionally attributed to male strength and dominance.

The combination of rigidity in strategic vision and flexibility in tactics created what can be described as the “Putin paradox.” He appears indispensable to the functioning of the Russian state, even as the costs of his leadership mount both internally and externally. Domestically, economic stagnation, demographic decline, corruption, and a narrowing base of political talent raise questions about the sustainability of his model. Internationally, prolonged confrontation with the West, reputational damage, and resource-draining military operations strain Russia’s capacity to project power.

Yet these very challenges reinforce the perception among the elites and much of the public that without Putin at the helm, the state would face fragmentation or collapse. In this way, Putin’s endurance is not only the product of his personal authority but also of a political architecture he has built to make his removal appear too risky for those within the system. The interplay of loyalty, fear, historical narrative, and adaptive governance ensures that even as pressures accumulate, the structure holds, at least for now.

The Endgame of Control

Putin’s political model illustrates both the resilience and fragility inherent in personalist autocracies. For more than two decades, he has successfully concentrated power by dismantling institutional checks, forging historical narratives, using repression, and altering legislation. Yet such concentration of authority is bound to leave the system vulnerable: repression cannot remain perpetual, and the risks of public discontent increase. Additionally, in the absence of institutional checks and regulations, questions loom about potential successors to Putin. This is the paradox of Putin’s hard rule: the very strength of his personality politics exposes the regime’s fragility, even as he has revived the myth of Russian imperial destiny—an ideological framework that continues to resonate with his people and shape the logic of his governance.

Recommended

Unity or Division Against China?

The Last Ayatollah

Trump’s America and the End of Global Trust

Trump’s War on Norms

Soft Power, Hard Tactics, and U.S. Resistance